Further reading

Establish Realistic IT Resource Management Practices

Holistically balance IT supply and demand to avoid overallocation.

Analyst perspective

Restore the right accountabilities for reconciling supply and demand.

"Who gets in trouble at the organization when too many projects are approved?

We’ve just exited a period of about 20-25 years where the answer to the above question was usually “nobody.” The officers of the corporation held nobody to account for the malinvestment of resources that comes from approving too many projects or having systemically unrealistic project due dates. Boards of directors failed to hold the officers accountable for that. And shareholders failed to hold boards of directors accountable for that.

But this is shifting right under our feet. Increasingly, PMOs are being managed with the mentality previously reserved for those in the finance department. In many cases, the PMOs are now reporting to the CFO! This represents a very simple and basic reversion to the concept of fiduciary duty: somebody will be held to account for the consumption of all those hours, and somebody should be the approver of projects who created the excess demand." – Barry Cousins Senior Director of Research, PMO Practice Info-Tech Research Group

Our understanding of the problem

This Research Is Designed For:

- IT leaders who lack actionable evidence of a resource-supply, work-demand imbalance.

- CIOs whose departments struggle to meet service and project delivery expectations with given resources.

- Portfolio managers, PMO directors, and project managers whose portfolio and project plans suffer due to unstable resource availability.

This Research Will Help You:

- Build trustworthy resource capacity data to support service and project portfolio management.

- Develop sustainable resource management practices to help you estimate, and continually validate, your true resource capacity for services and projects.

- Identify the demands that deplete your resource capacity without creating value for IT.

This Research Will Also Assist:

- Steering committee and C-suite management who want to improve IT’s delivery of projects.

- Project sponsors that want to ensure their projects get the promised resource time by their project managers.

This Research Will Help Them:

- Ensure sufficient supply of time for projects to be successfully completed with high quality.

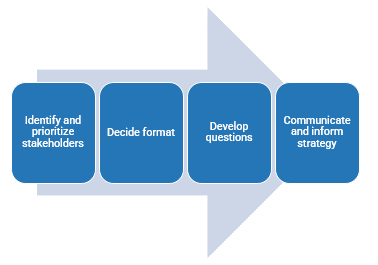

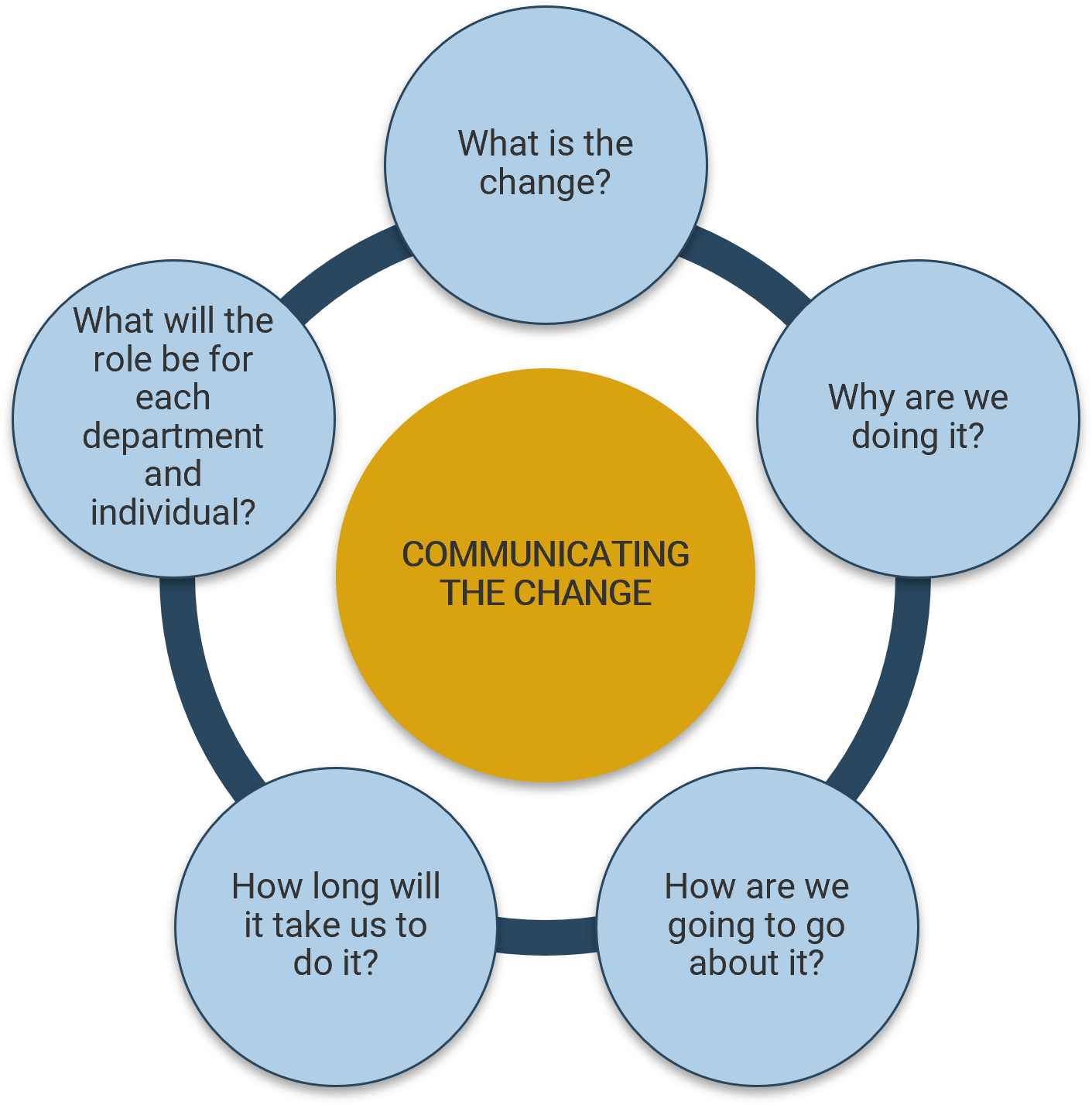

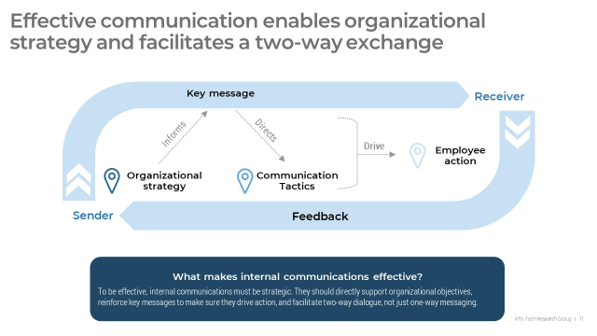

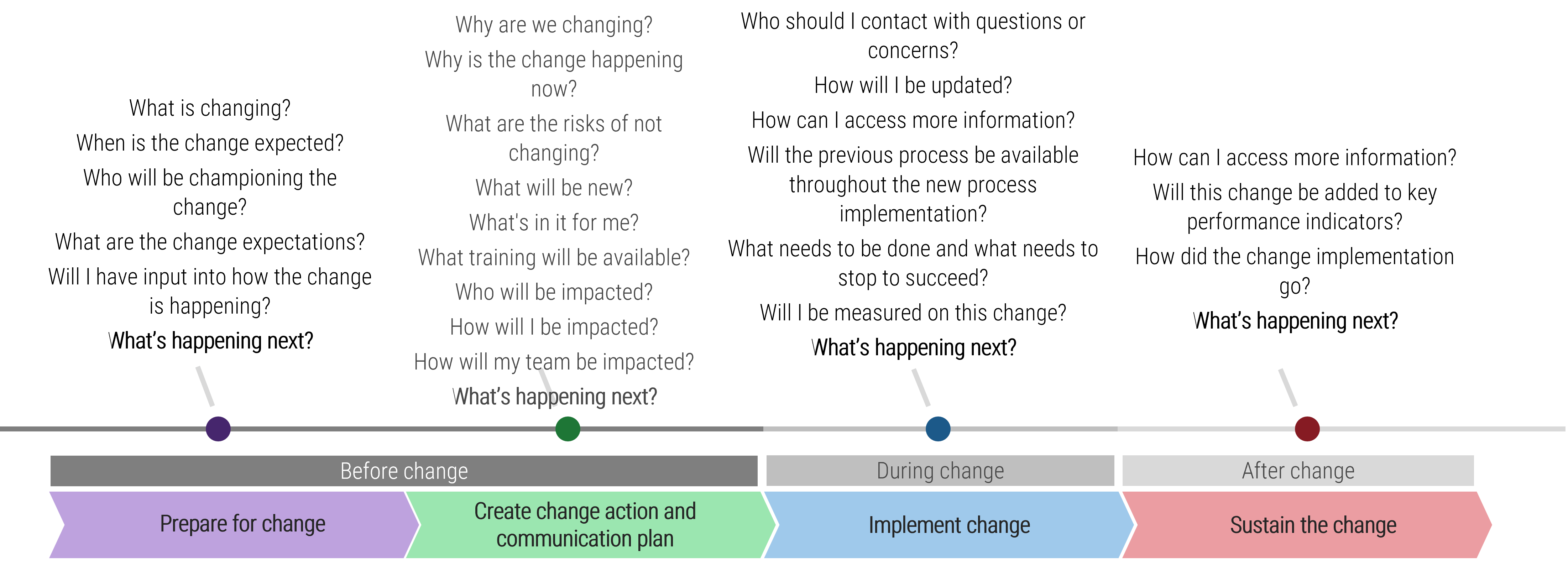

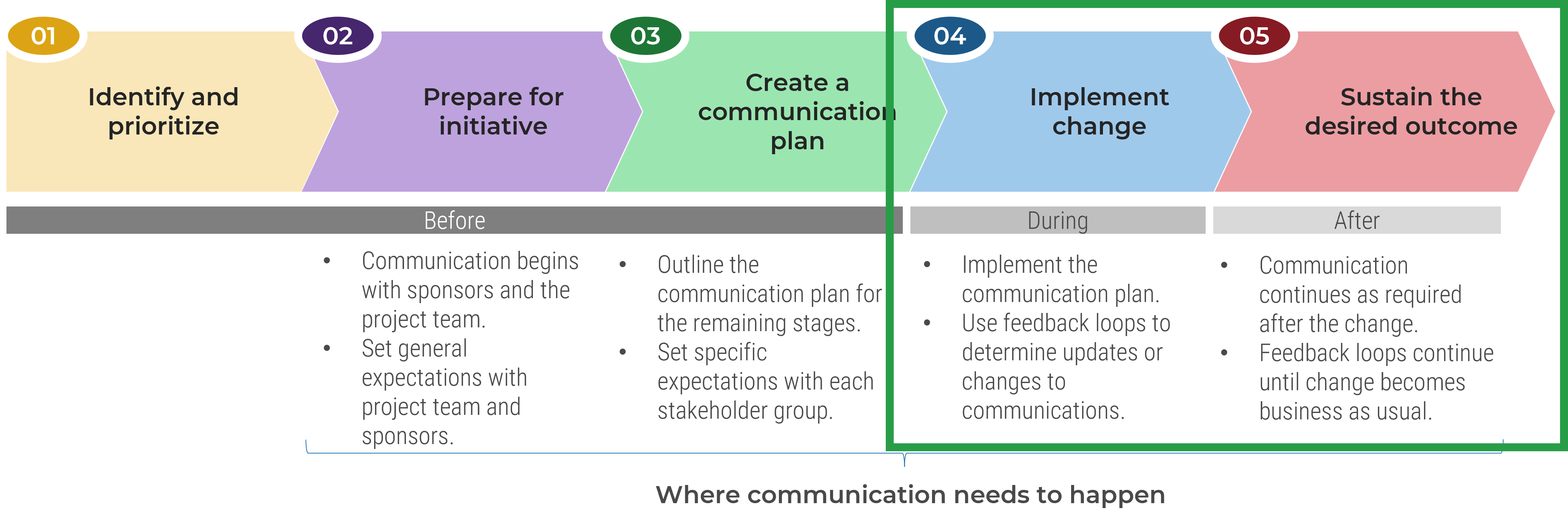

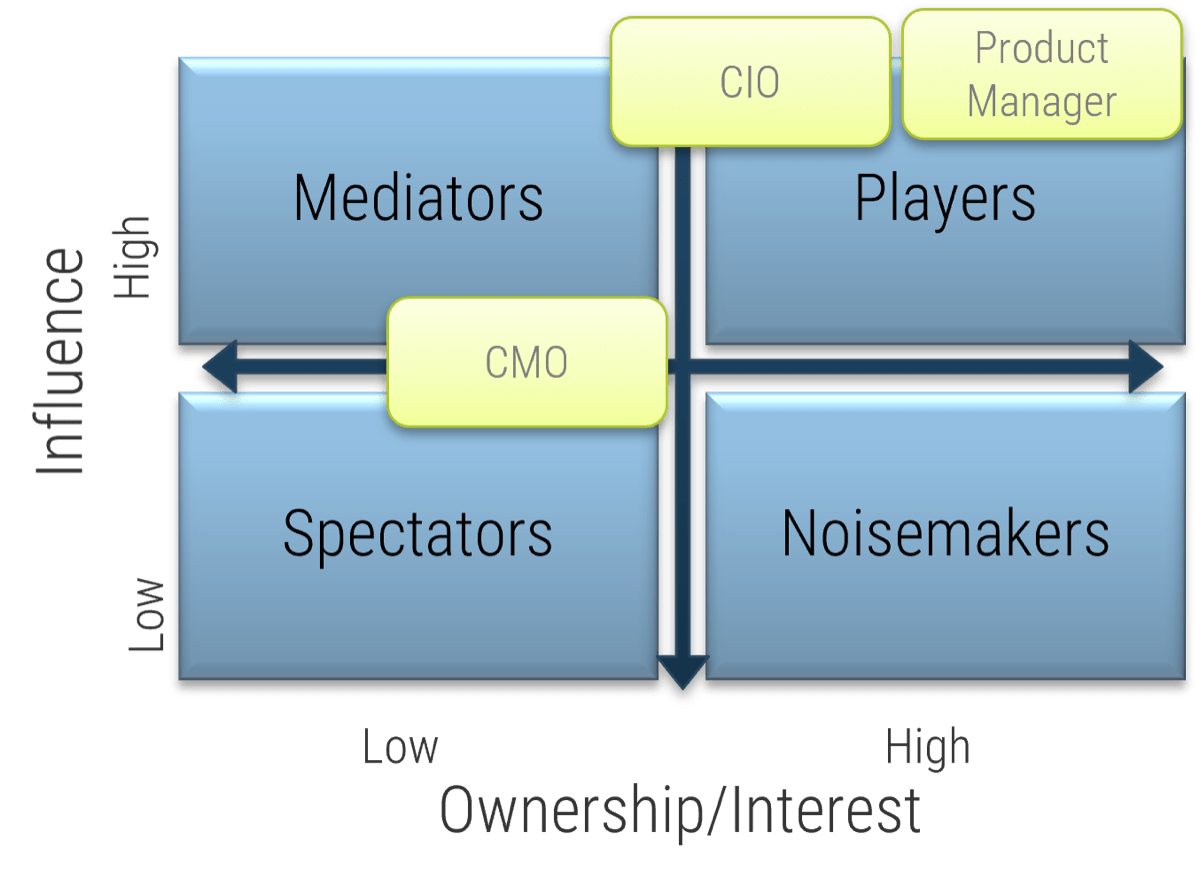

- Communicate the new resource management practice and get stakeholder buy-in.

Executive summary

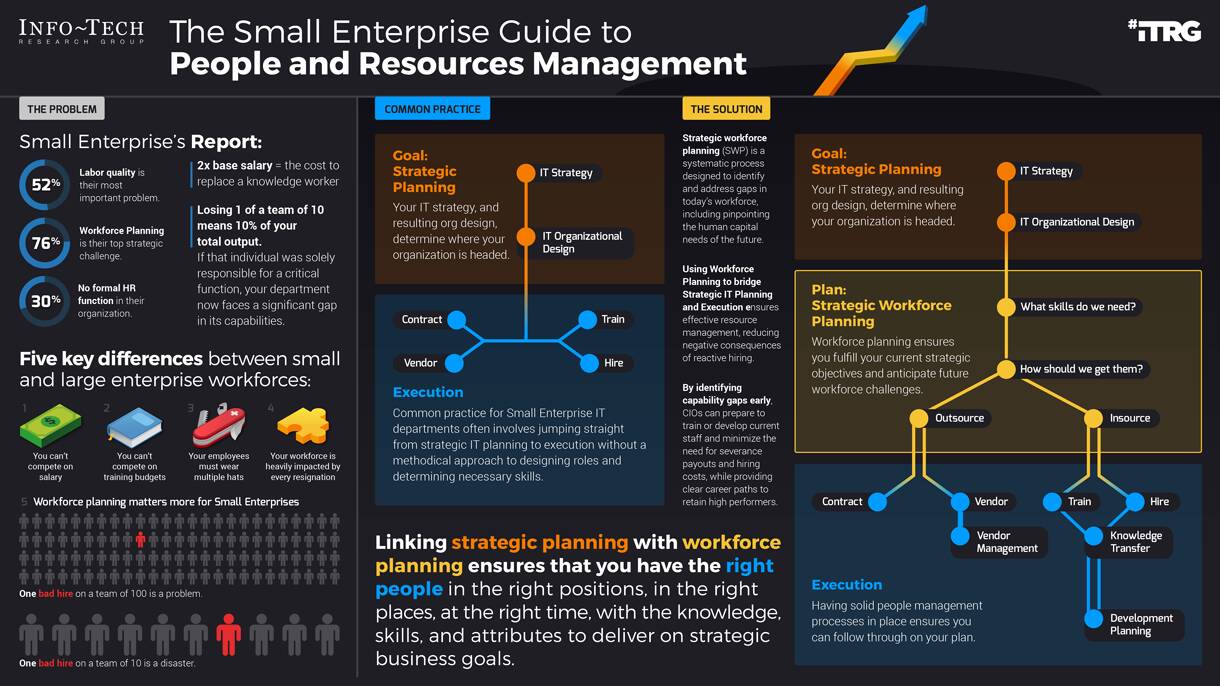

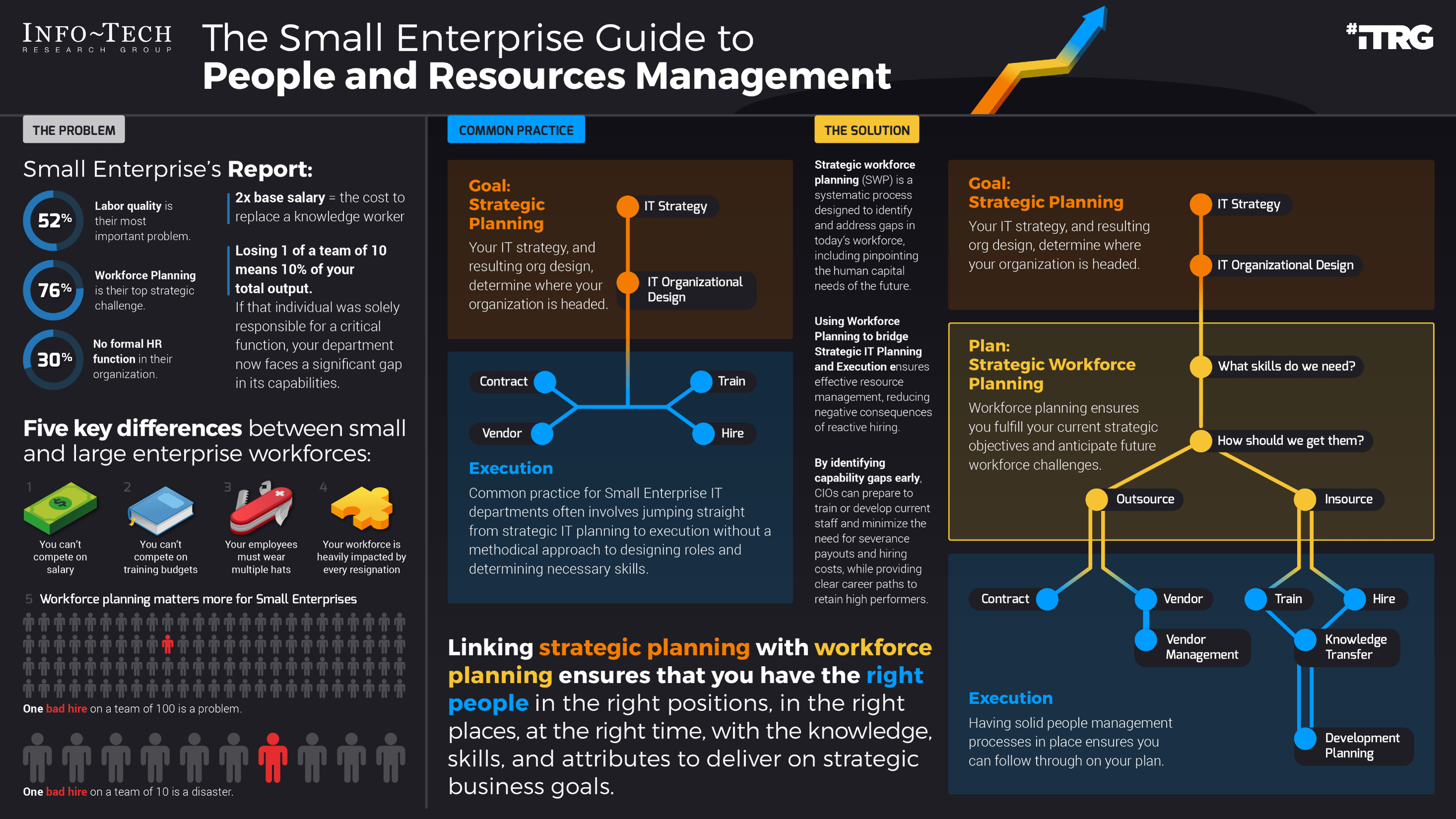

Situation

- As CIO, you oversee a department that lacks the resource capacity to adequately meet organizational demand for new projects and services. As a result, project quality and timelines suffer, and service delivery lags.

- You need a resource management strategy to help bring balance to supply and demand in order to improve IT’s ability to deliver.

Complication

- The shift to matrix work structures has strained traditional methods of time tracking. Day-to-day demand is chaotic; staff are pulled in multiple directions by numerous people, making usable capacity data elusive.

- The executive team approves too many projects, but is not held to account for the overspend on time. Instead, the IT worker is made liable, expected to simply get things done under excessive demands.

Resolution

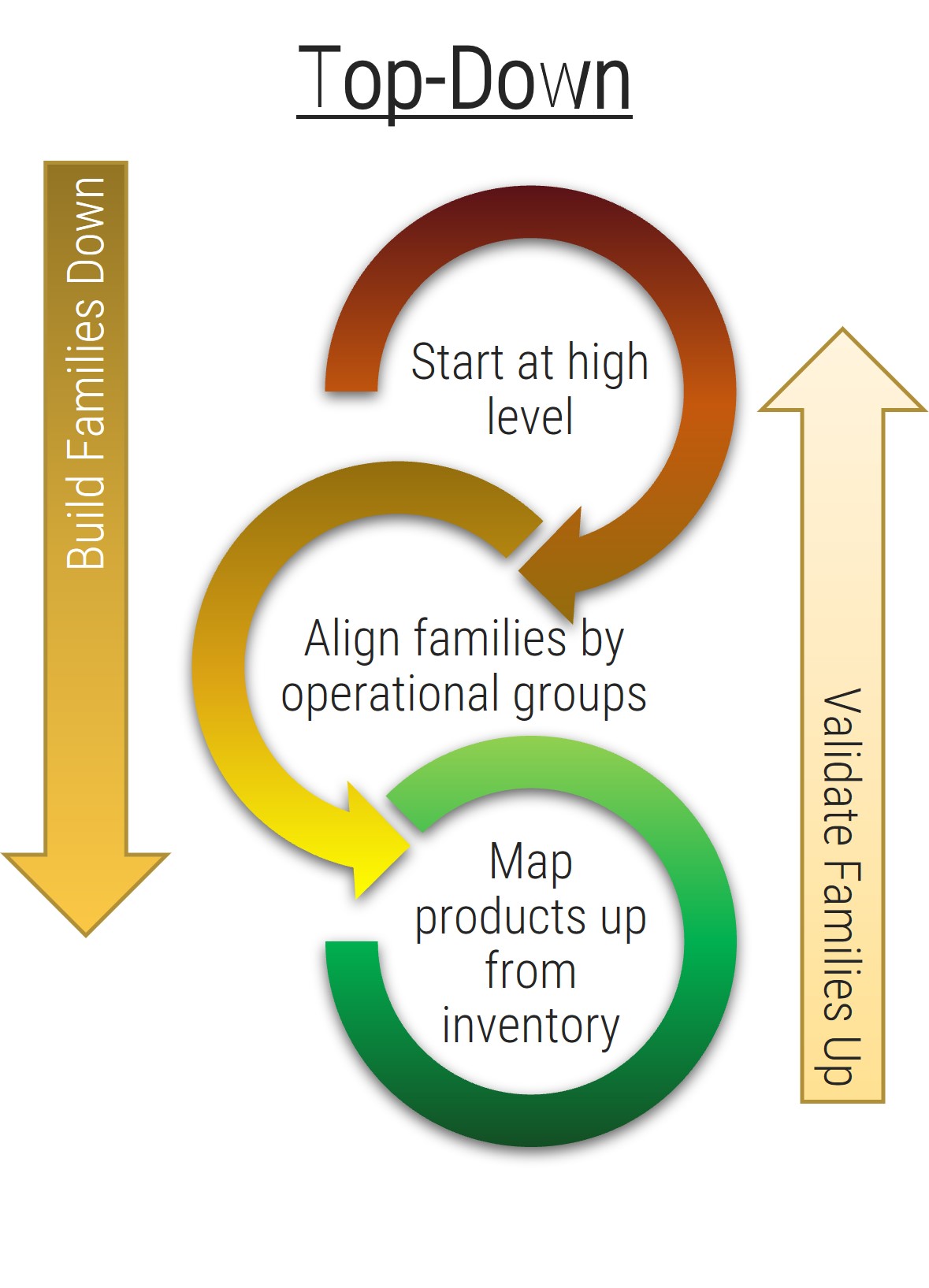

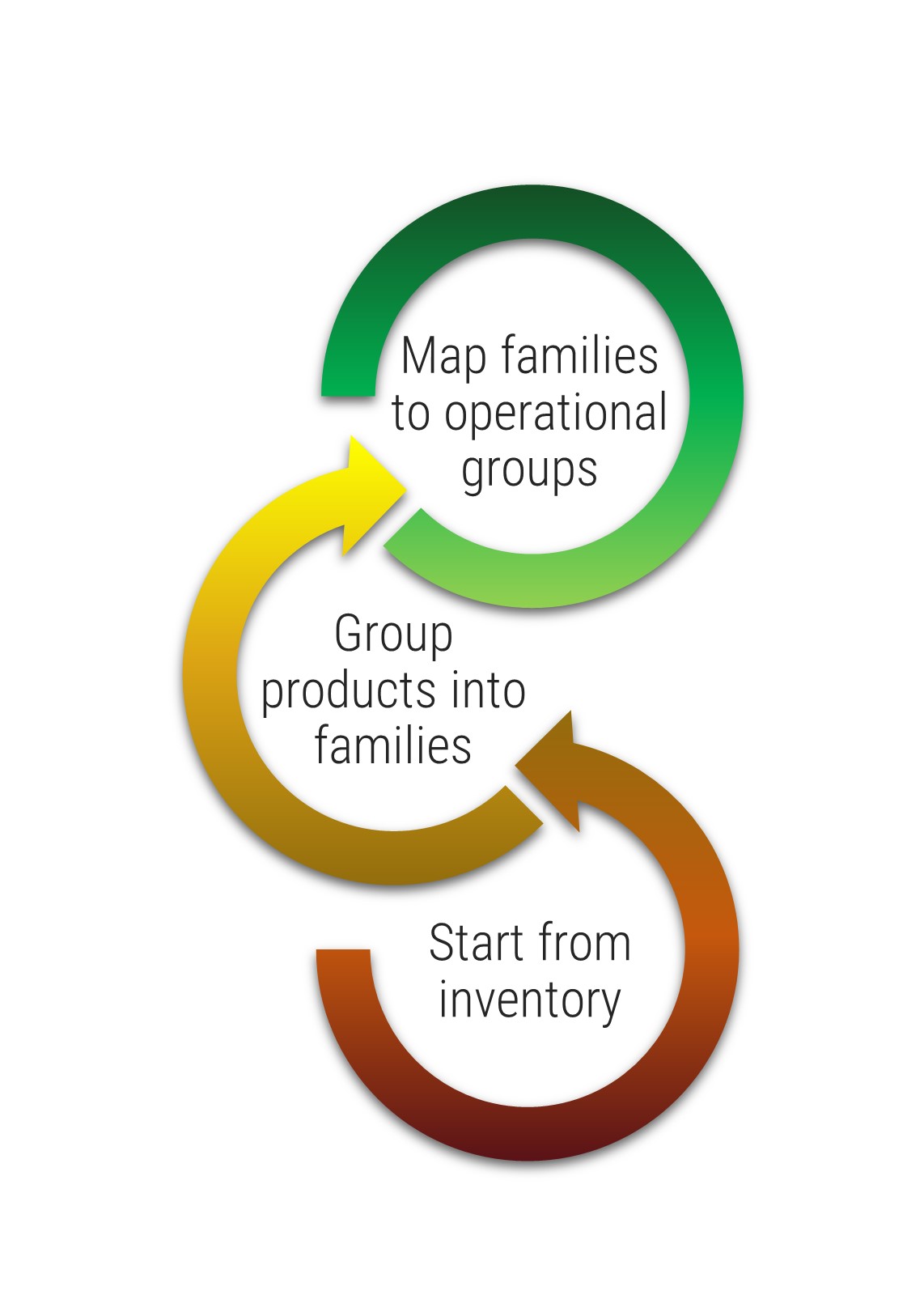

- Instill a culture of capacity awareness. For years, the project portfolio management (PPM) industry has helped IT departments report on demand and usage, but it has largely failed to make capacity part of the conversation. This research helps inject capacity awareness into project and service portfolio planning, enabling IT to get proactive about constraints before overallocation spirals, and project and service delivery suffers.

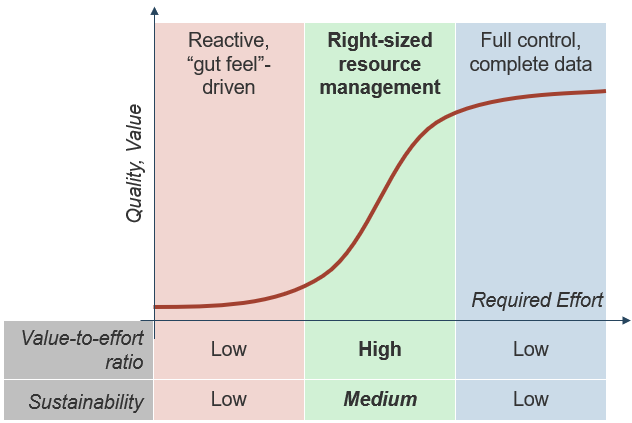

- Build a sustainable process. Efforts to get better at resource management often falter when you try to get too granular too quickly. Info-Tech’s approach starts at a high level, ensuring that capacity data is accurate and usable, and that IT’s process discipline is mature enough to maintain the data, before drilling down into greater levels of precision.

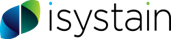

- Establish a capacity hub. You will ultimately need a tool to help provide ongoing resource visibility. Follow the advice in this blueprint to help with your tool selection and ensure the reporting needs of both your team and executives are met.

Info-Tech Insight

- Take a realistic approach to resource management. New organizational realities have made traditional, rigorous resource projections impossible to maintain. Accept reality and get realistic about where IT’s time goes.

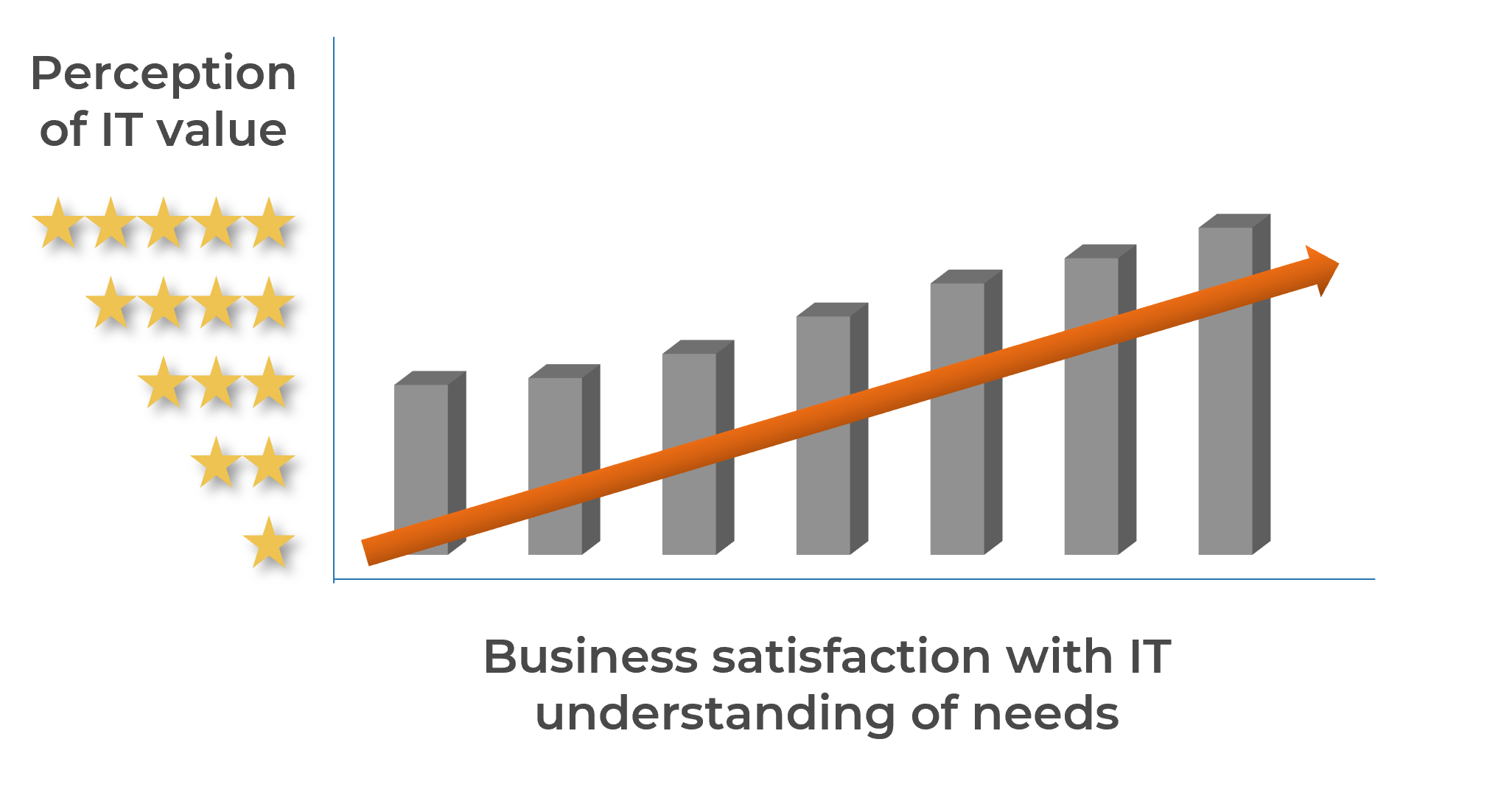

- Make IT’s capacity perpetually transparent. The best way to ensure projects are approved and scheduled based upon the availability of the right teams and skills is to shine a light into IT’s capacity and hold decision makers to account with usable capacity reports.

The availability of staff time is rarely factored into IT project and service delivery commitments

As a result, a lot gets promised and worked on, and staff are always busy, but very little actually gets done – at least not within given timelines or to expected levels of quality.

Organizations tend to bite off more than they can chew when it comes to project and service delivery commitments involving IT resources.

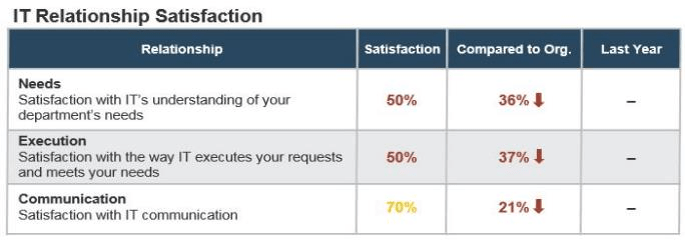

While the need for businesses to make an excess of IT commitments is understandable, the impacts of systemically overallocating IT are clearly negative:

- Stakeholder relations suffer. Promises are made to the business that can’t be met by IT.

- IT delivery suffers. Project timelines and quality frequently suffer, and service support regularly lags.

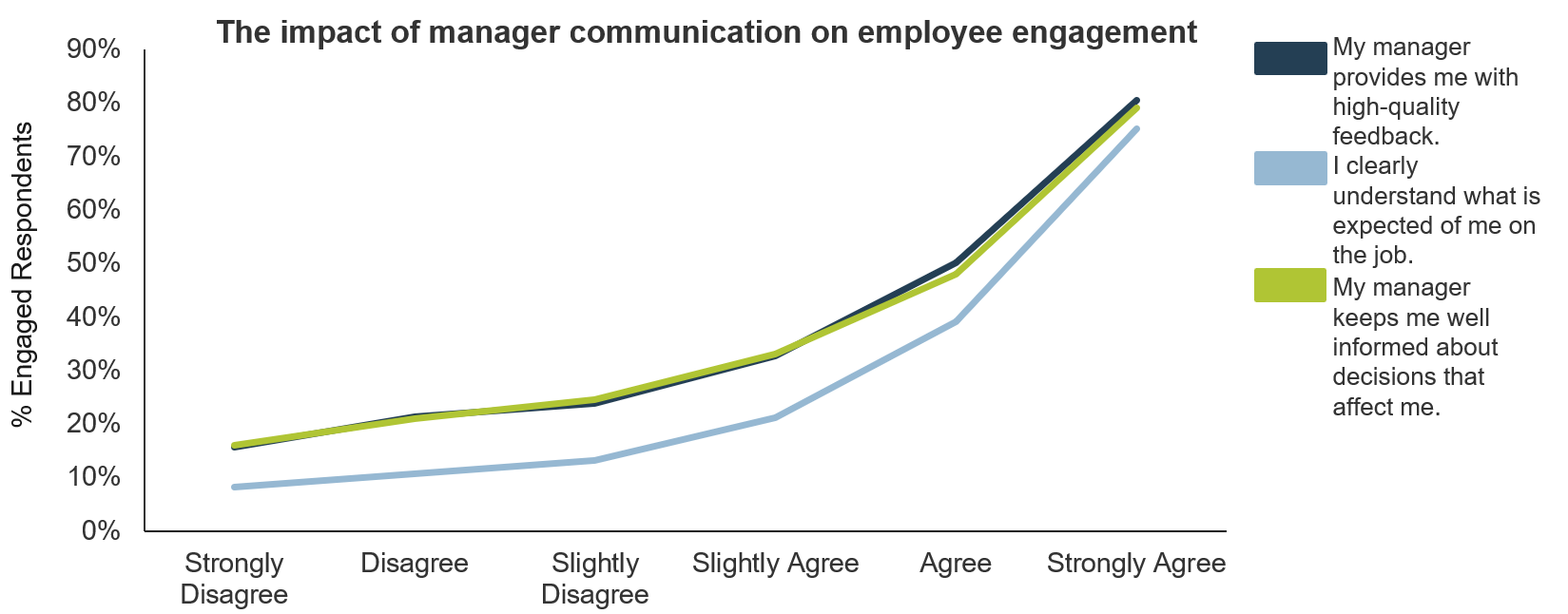

- Employee engagement suffers. Anxiety and stress levels are consistently high among IT staff, while morale and engagement levels are low.

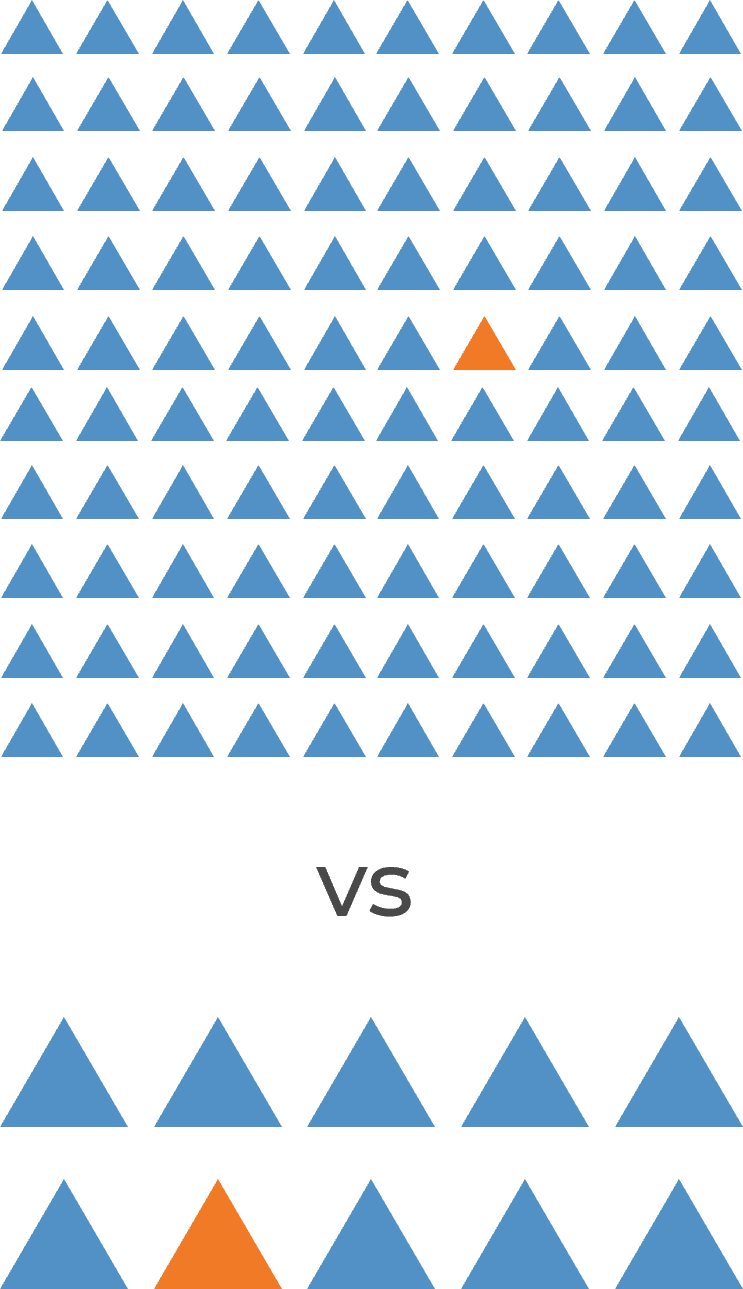

76% of organizations say they have too many projects on the go and an unmanageable and ever-growing backlog of things to get to. (Cooper, 2014)

Almost 70% of workers feel as though they have too much work on their plates and not enough time to do it. (Reynolds, 2016)

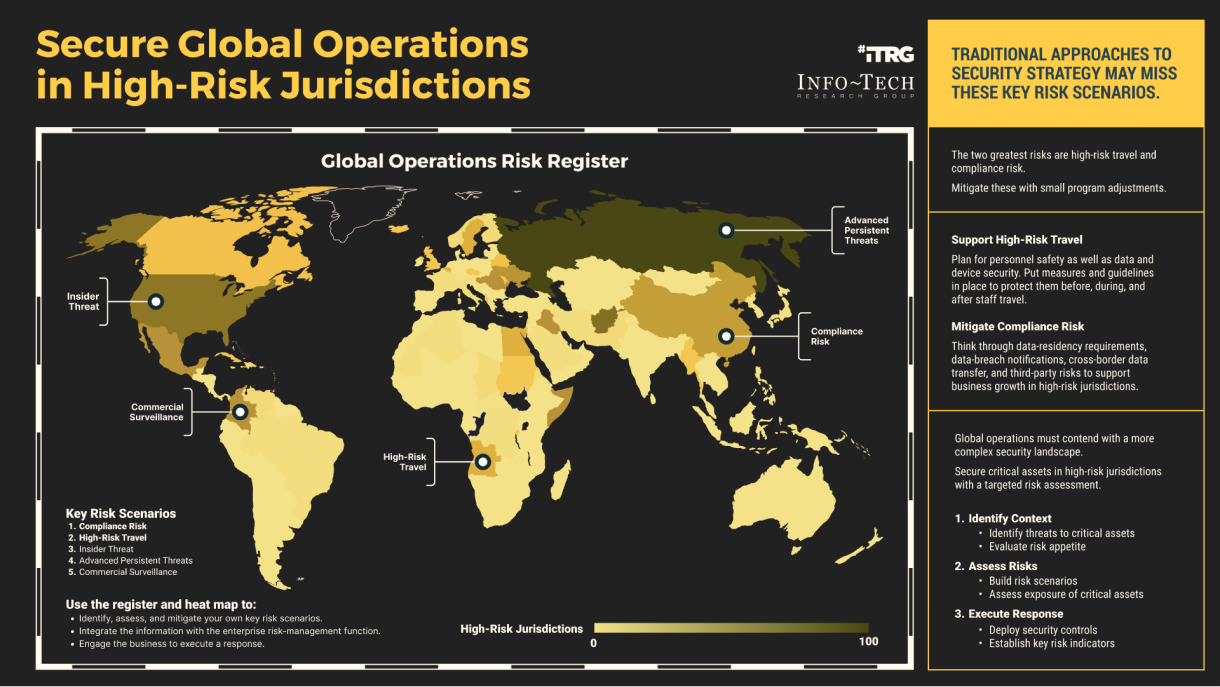

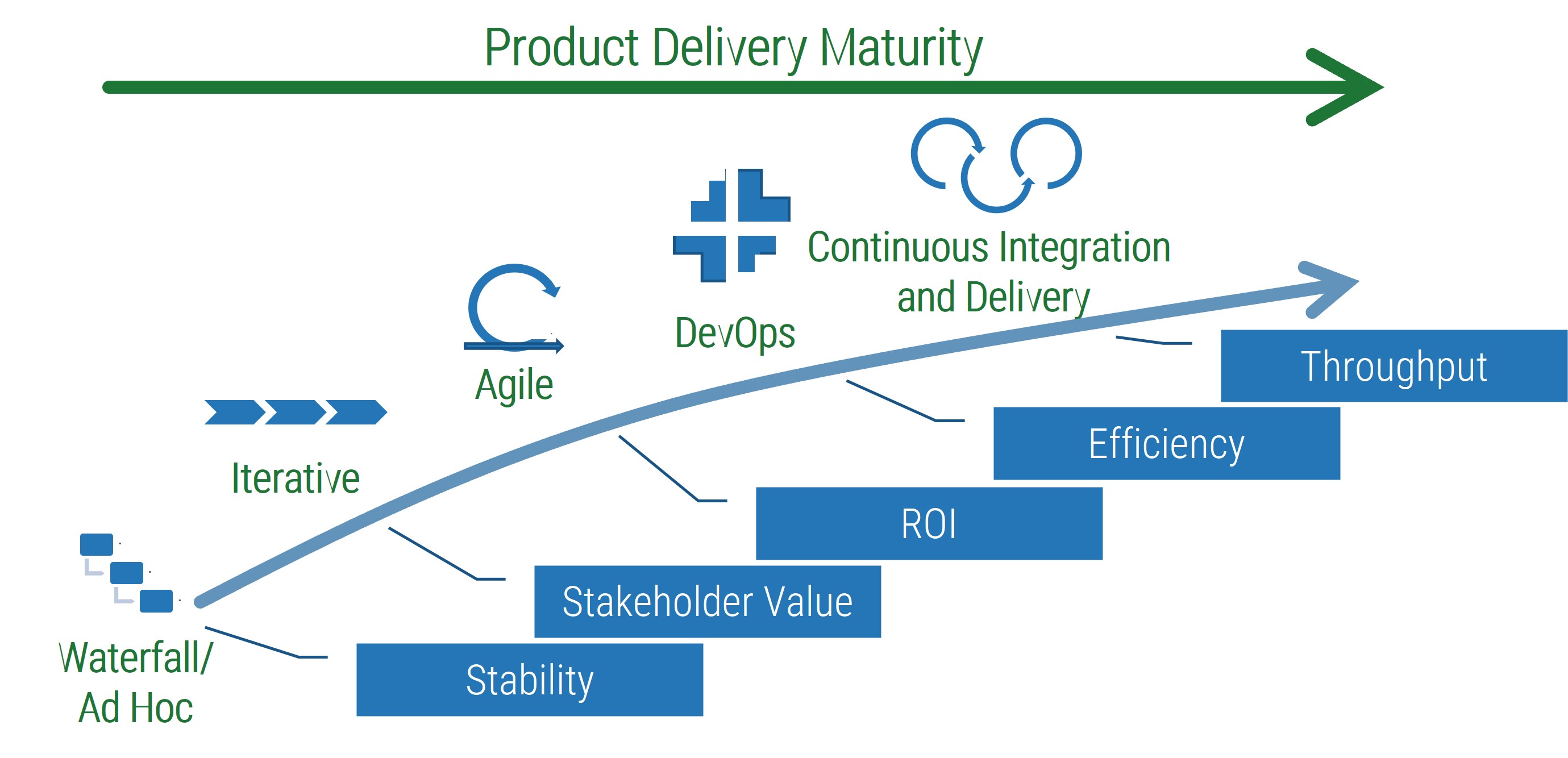

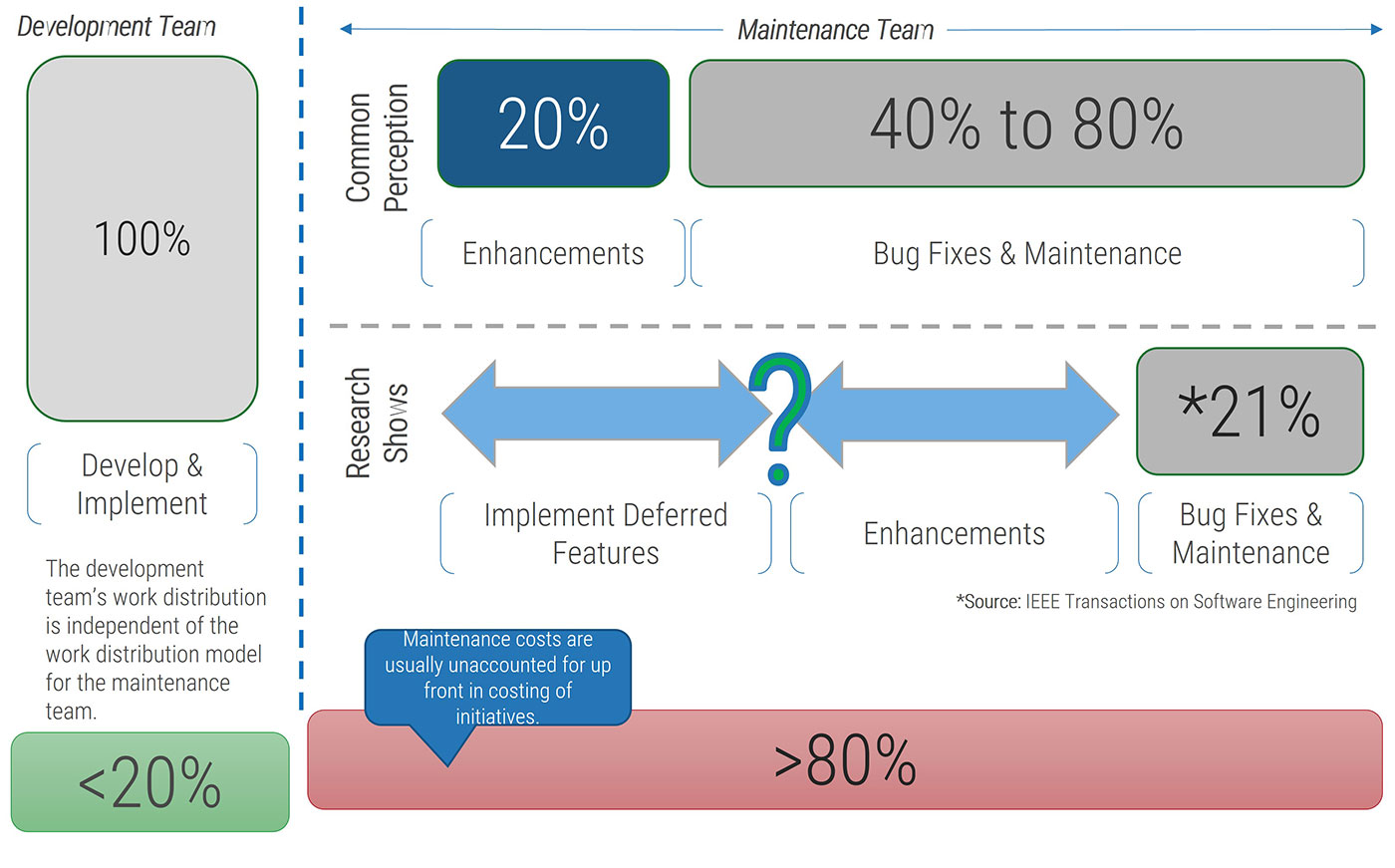

Resource management can help to improve workloads and project results, but traditional approaches commonly fall short

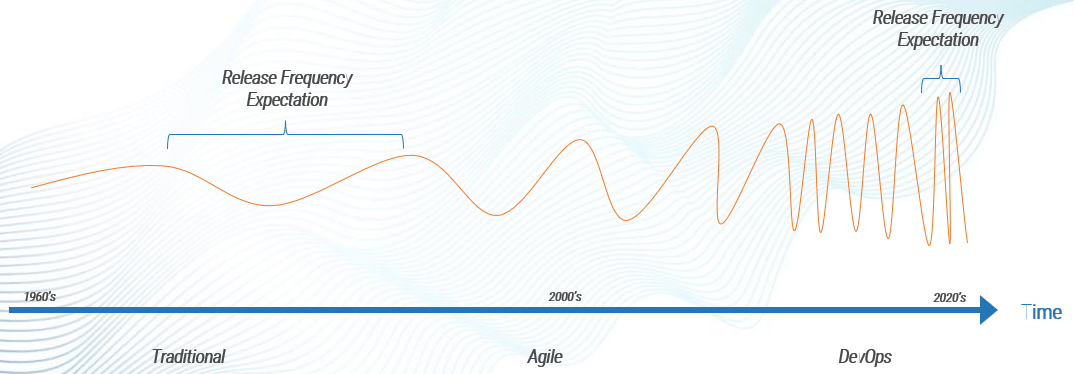

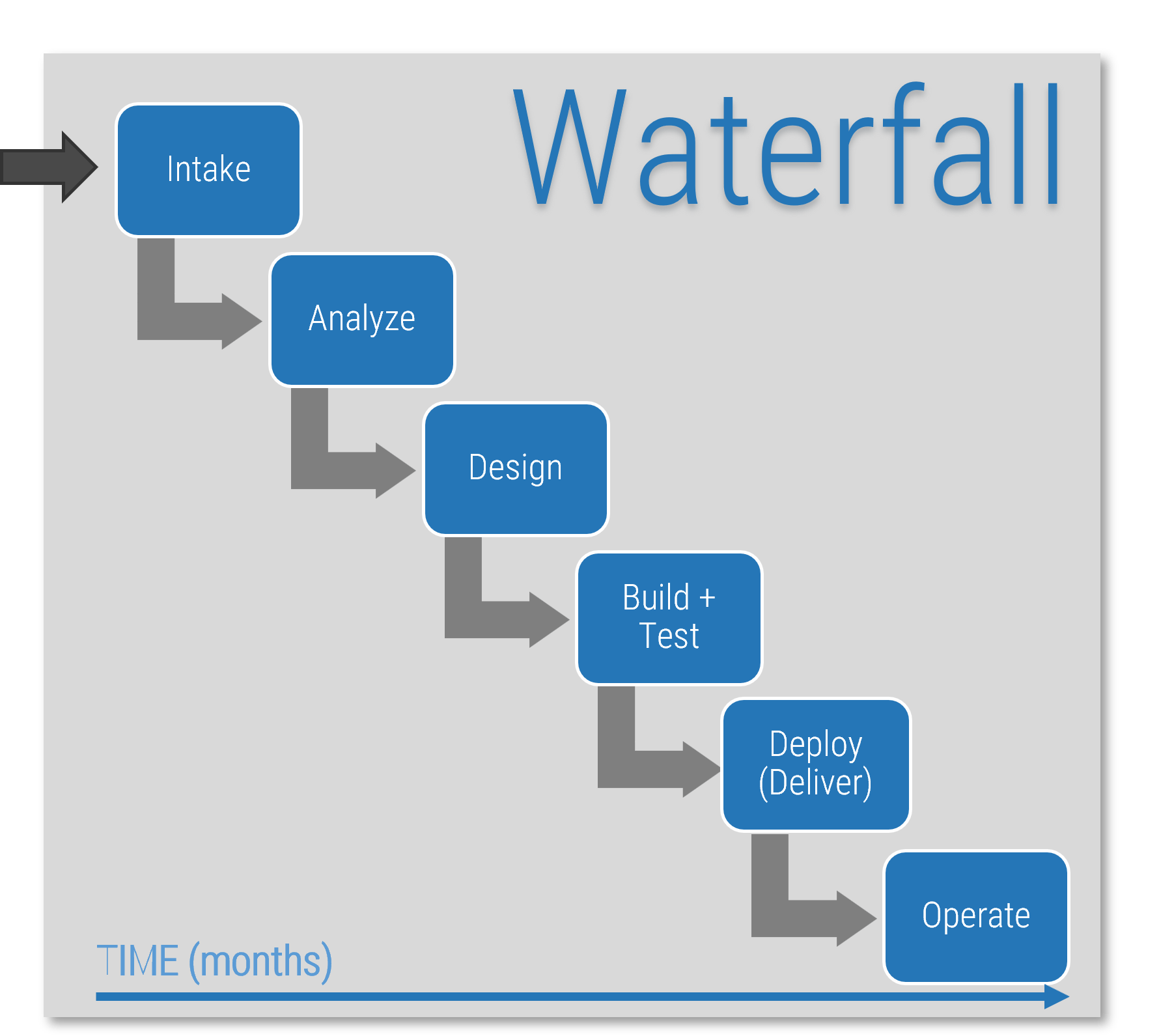

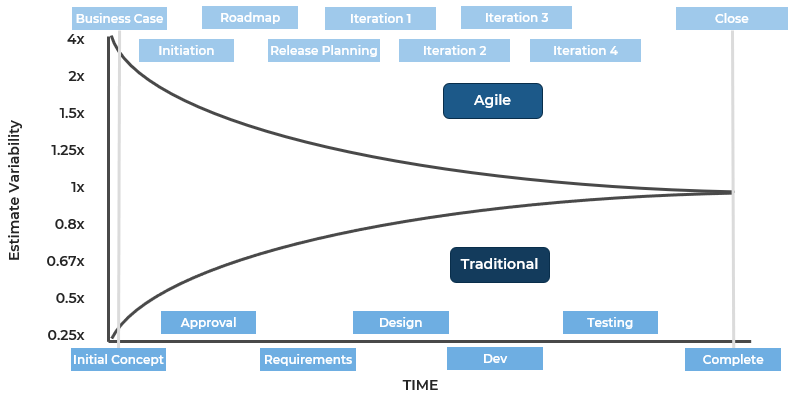

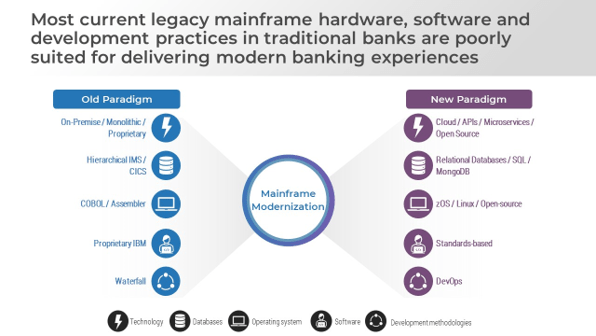

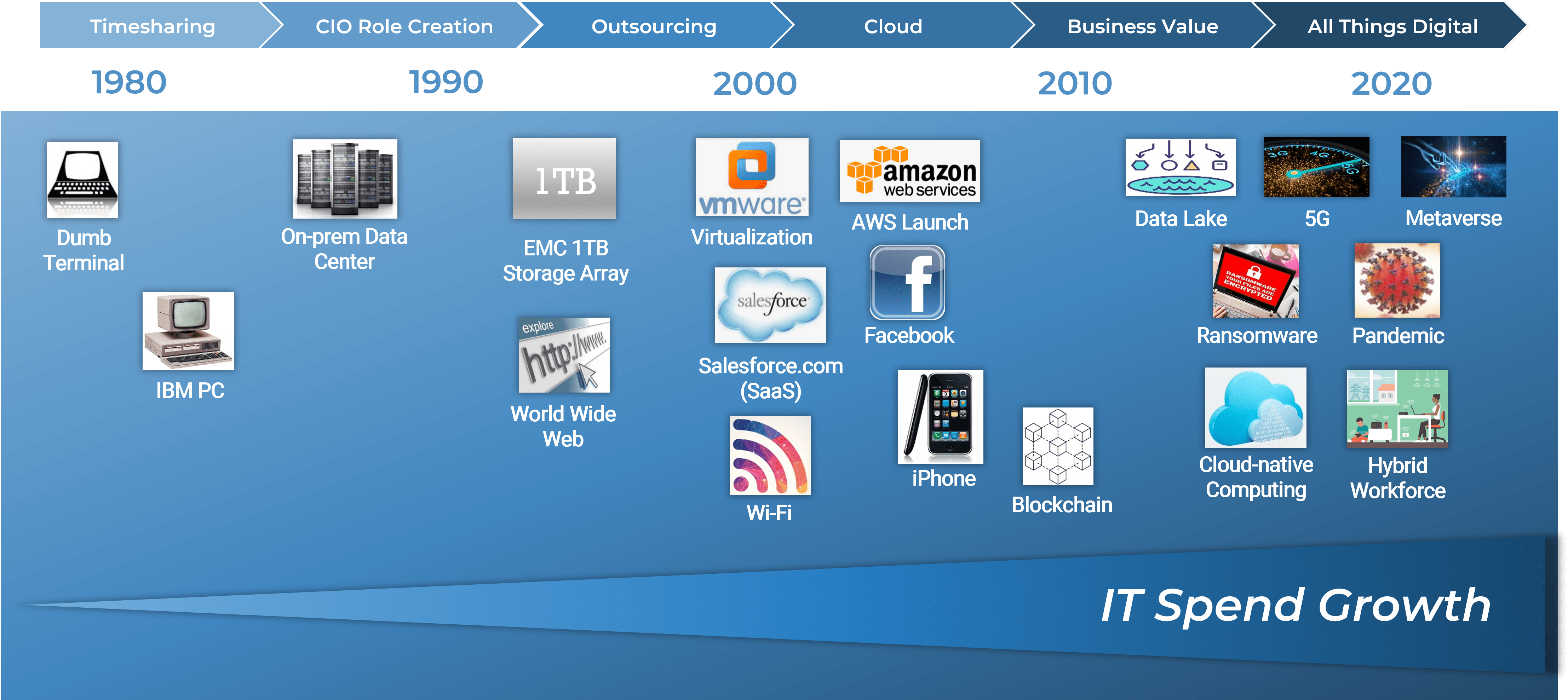

Traditional approaches to resource management suffer from a fundamental misconception about the availability of time in 2017.

The concept of resource management comes from a pre-World Wide Web era, when resource and project plans could be based on a relatively stable set of assumptions.

In the old paradigm, the availability of time was fairly predictable, as was the demand for IT services, so there was value to investing time into rigorous demand forecasts and planning.

Resource projections could be based in a secure set of assumptions – i.e. 8 hour days, 40 hour weeks – and staff had the time to support detailed resource management processes that provided accurate usage data.

Old Realities

- Predictability. Change tended to be slow and deliberate, providing more stability for advanced, rigorous demand forecasts and planning.

- Fixed hierarchy. Tasks, priorities, and decisions were communicated through a fixed chain of command.

- Single-task focus. The old reality was more accommodating to sustained focus on one task at a time.

96% of organizations report problems with the accuracy of information on employee timesheets. (Dimensional, 2013)

Old reality resource forecasting inevitably falters under the weight of unpredictable demands and constant distractions

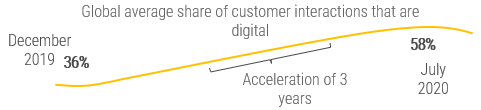

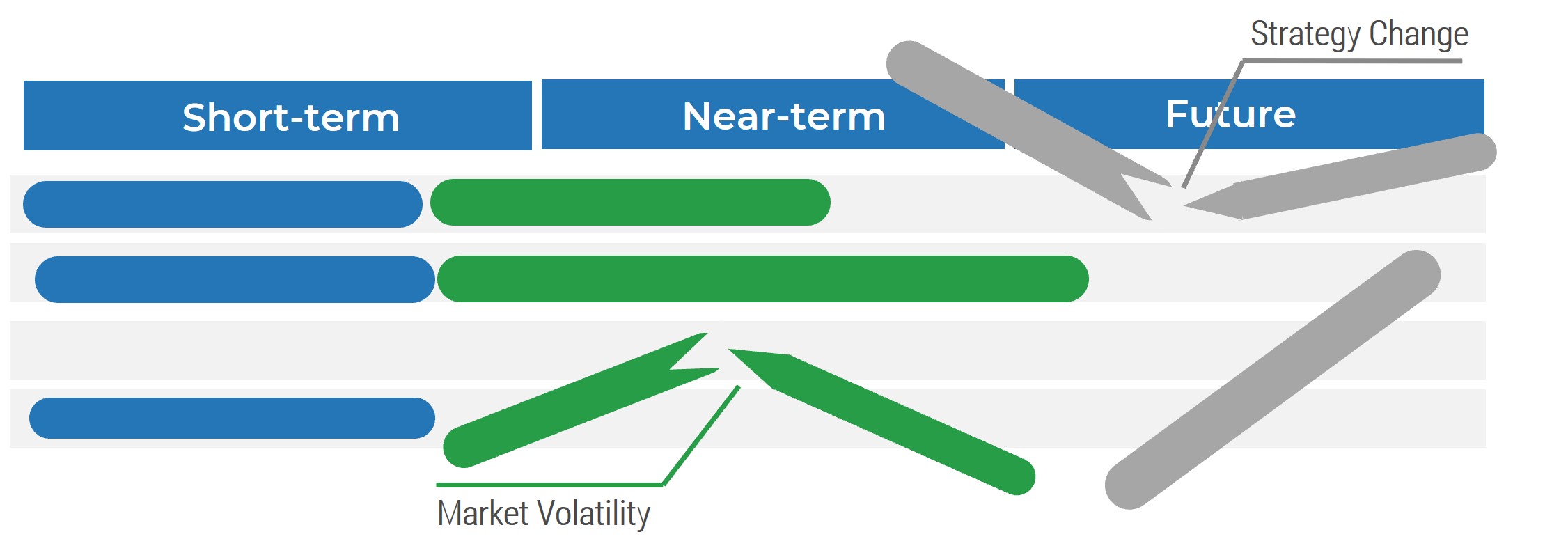

New realities are causing demands on workers’ time to be unpredictable and unrelenting, making a sustained focus on a specific task for any length of time elusive.

Part of the old resource management mythology is the idea that a person can do (for example) eight different one-hour tasks in eight hours of continuous work. This idea has gone from harmlessly mistaken to grossly unrealistic.

The predictability and focus have given way to more chaotic workplace realities. Technology is ubiquitous, and the demand for IT services is constant.

A day in IT is characterized by frequent task-switching, regular interruptions, and an influx of technology-enabled distractions.

Every 3 minutes and 5 seconds: How often the typical office worker switches tasks, either through self-directed or other-directed interruptions. (Schulte, 2015)

12 minutes, 40 seconds: The average amount of time in-between face-to-face interruptions in matrix organizations. (Anderson, 2015)

23 minutes, 15 seconds: The average amount of time it takes to become on task, productive, and focused again after an interruption. (Schulte, 2015)

759 hours: The average number of hours lost per employee annually due to distractions and interruptions. (Huth, 2015)

The validity of traditional, rigorous resource planning has long been an illusion. New realities are making the sustained focus and stable assumptions that old reality projections relied on all but impossible to maintain.

For resource management practices to be effective, they need to evolve to meet new realities

New organizational realities have exacerbated traditional approaches to time tracking, making accurate and usable resource data elusive.

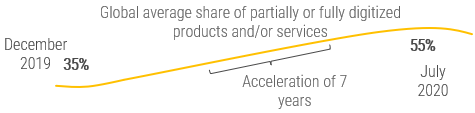

The technology revolution that began in the 1990s ushered in a new paradigm in organizational structures. Matrix reporting structures, diminished supervision of knowledge workers, massive multi-tasking, and a continuous stream of information and communications from the outside world have smashed the predictability and stability of the old paradigm.

The resource management industry has largely failed to evolve. It remains stubbornly rooted in old realities, relying on calculations and rollups that become increasingly unsustainable and irrelevant in our high-autonomy staff cultures and interruption-driven work days.

New Realities

- Unpredictable. Technologies and organizational strategies change before traditional IT demand forecasts and project plans can be realized.

- Matrix management. Staff can be accountable to multiple project managers and functional managers at any given time.

- Multi-task focus. In the new reality, workers’ attentions are scattered across multiple tasks and projects at any given time.

87% of organizations report challenges with traditional methods of time tracking and reporting. (Dimensional, 2013)

40% of working time is not tracked or tracked inaccurately by staff. (actiTIME, 2016)

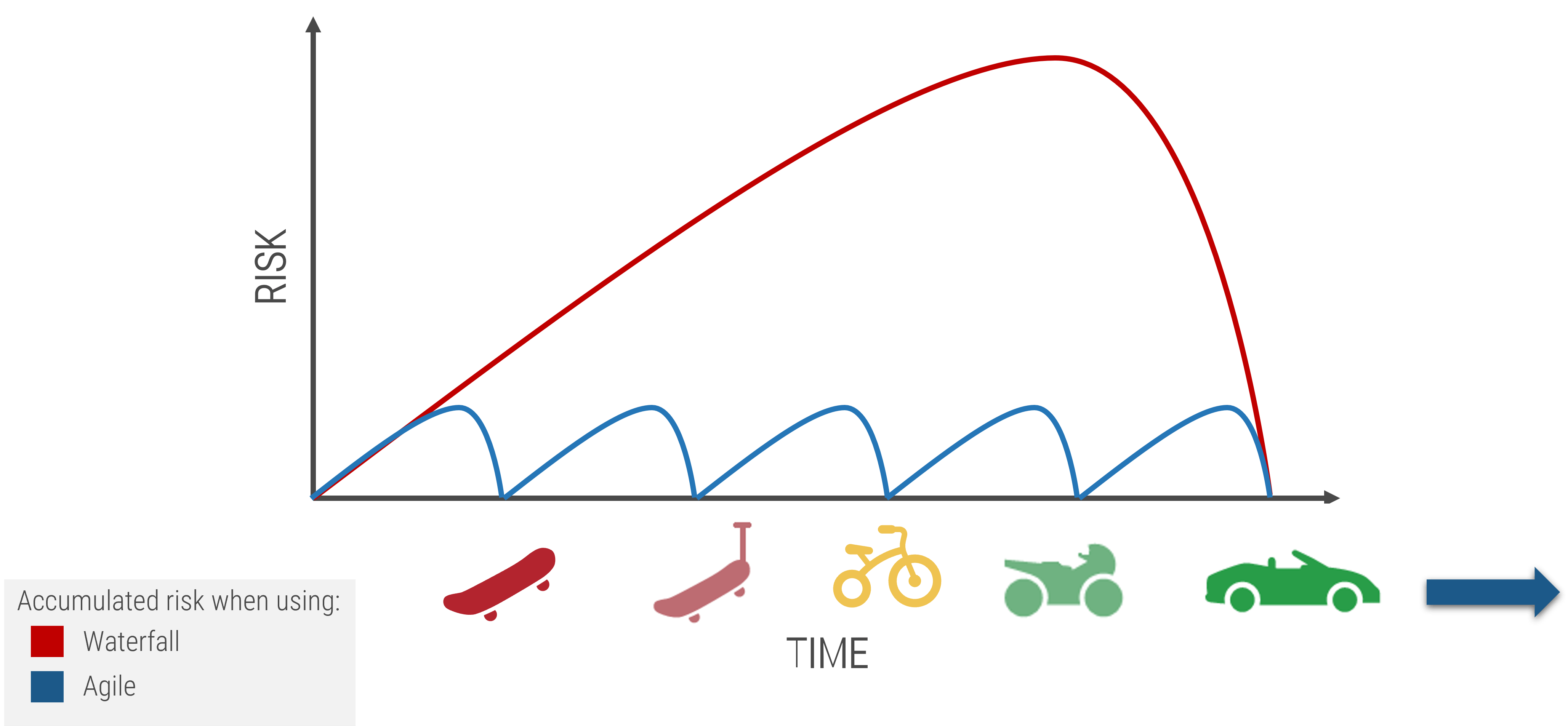

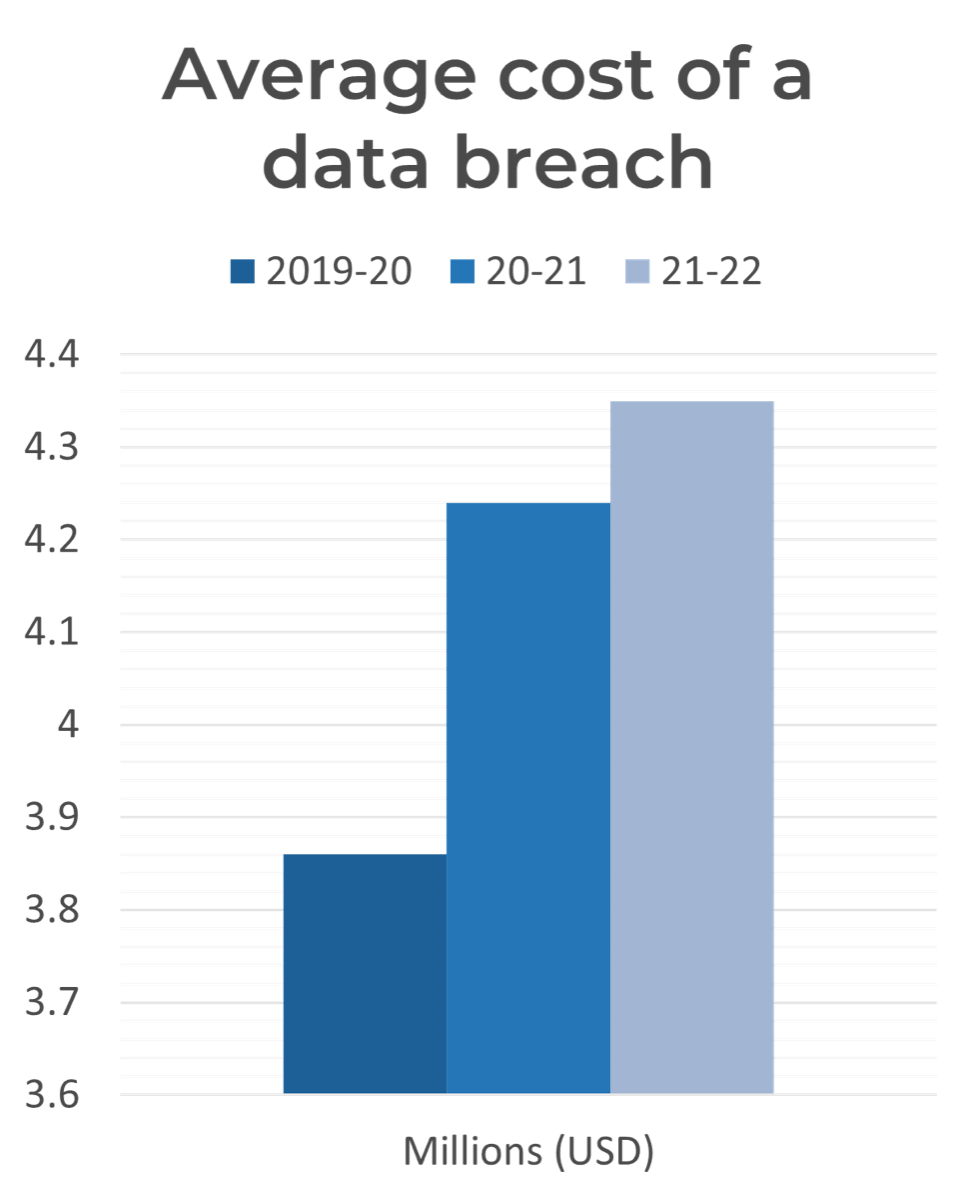

Poor resource management practices cost organizations dearly

While time is money, the statistics around resource visibility and utilization suggest that the vast majority of organizations don’t spend their available time all that wisely.

Research shows that ineffective resource management directly impacts an organization’s bottom line, contributing to such cost drains as the systemic late delivery of projects and increased project costs.

Despite this, the majority of organizations fail to treat staff time like the precious commodity it is.

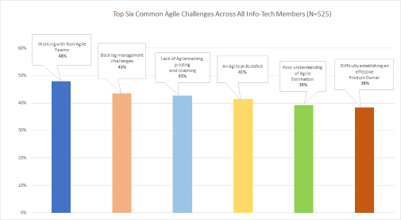

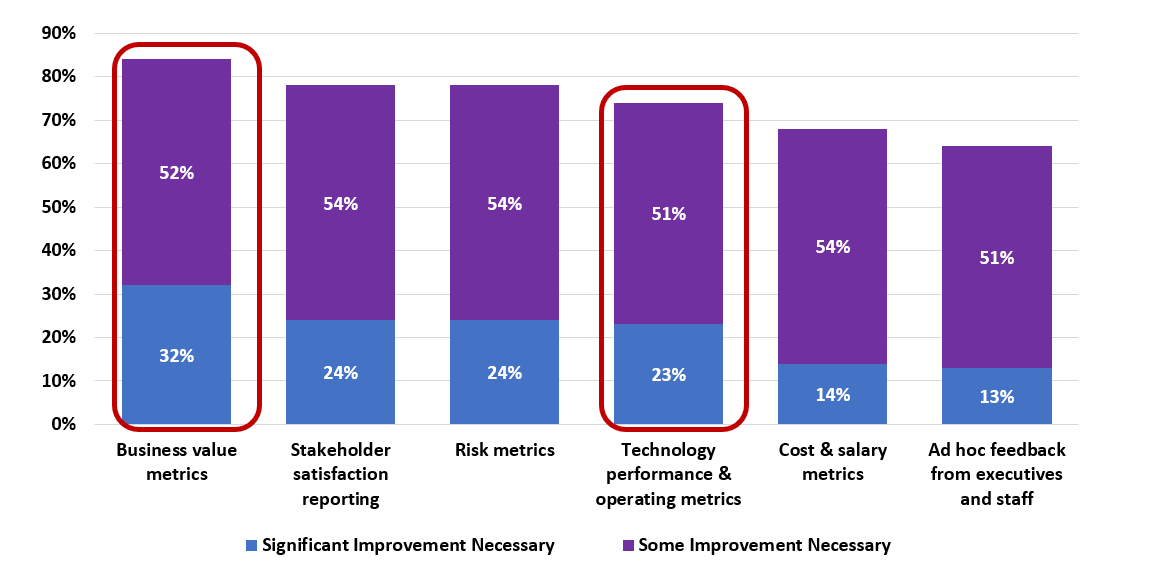

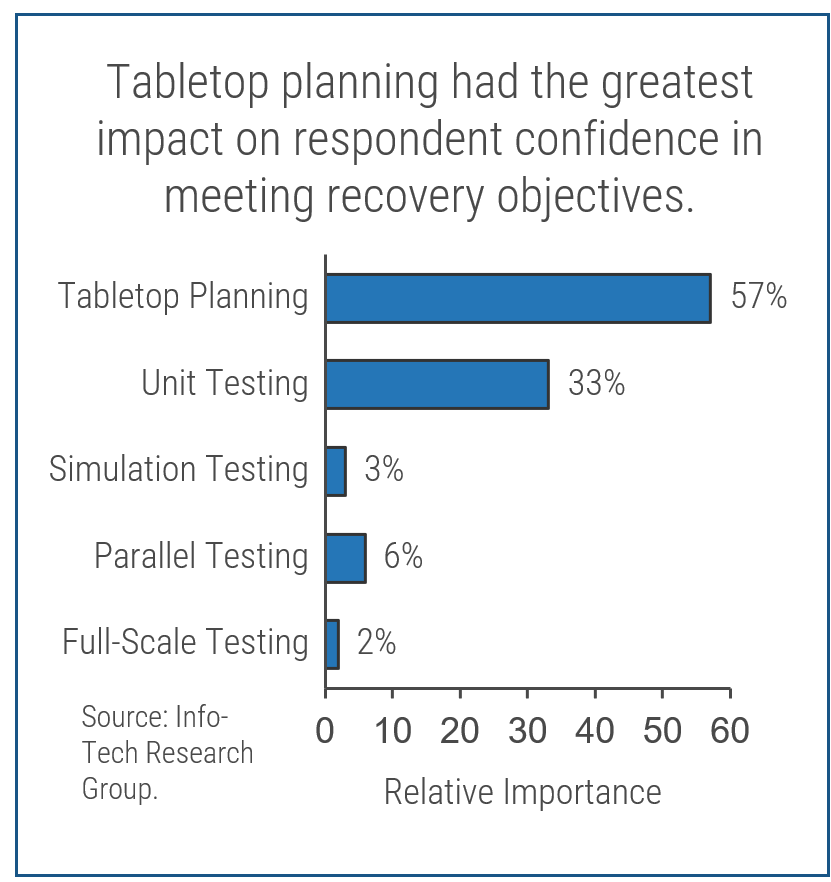

As the results of a 2016 survey show, the top three pain points for IT and PMO leaders all revolve around a wider cultural negligence concerning staff time (Alexander, TechRepublic, 2016):

- Overcommitted resources

- Constant change that affects staff assignments

- An inability to prioritize shared resources

Top risks associated with poor resource management

Inability to complete projects on time – 52%

Inability to innovate fast enough – 39%

Increased project costs – 38%

Missed business opportunities – 34%

Dissatisfied customers or clients – 32%

12 times more waste – Organizations with poor resource management practices waste nearly 12 times more resource hours than high-performing organizations. (PMI, 2014)

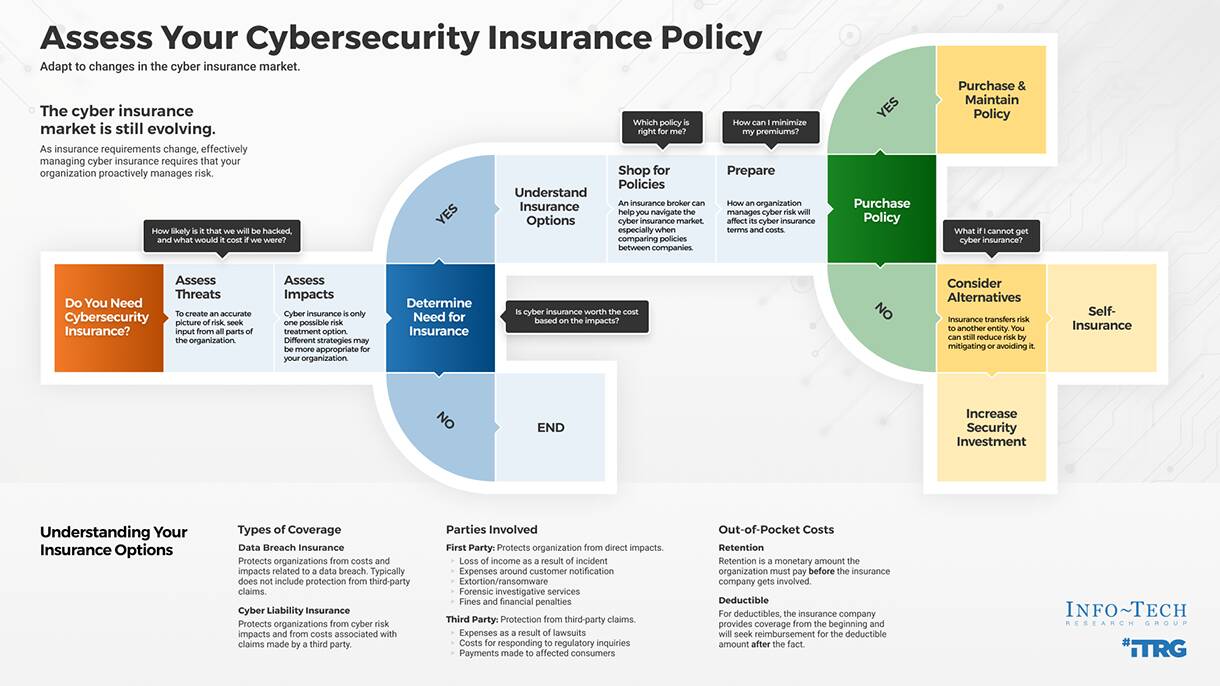

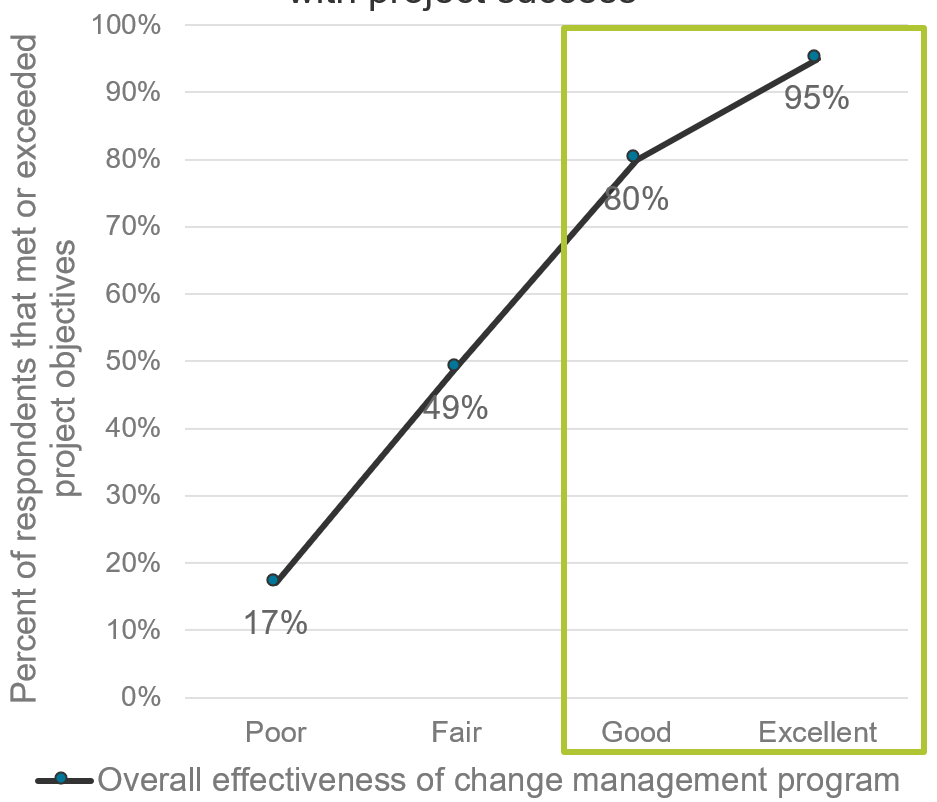

The concept of fiduciary duty represents the best way to bring balance to supply and demand, and improve project outcomes

Unless someone is accountable for controlling the consumption of staff hours, too much work will get approved and committed to without evidence of sufficient resourcing.

Who is accountable for controlling the consumption of staff hours?

In many ways, no question is more important to the organization’s bottom line – and certainly, to the effectiveness of a resource management strategy.

Historically, the answer would have been the executive layer of the organization. However, in the 1990s management largely abdicated its obligation to control resources and expenditures via “employee empowerment.”

Controls on approvals became less rigid, and accountability for choosing what to do (and not do) shifted onto the shoulders of the individual worker. This creates a current paradigm where no one is accountable for the malinvestment…

…of resources that comes from approving too many projects. Instead, it’s up to individual workers to sink-or-swim, as they attempt to reconcile, day after day, seemingly infinite organizational demand with their finite supply of working hours.

If your organization has higher demand (i.e. approved project work) than supply (i.e. people’s time), your staff will be the final decision makers on what does and does NOT get worked on.

Effective time leadership distinguishes top performing senior executives

"Everything requires time… It is the one truly universal condition. All work takes place in time and uses up time. Yet most people take for granted this unique, irreplaceable and necessary resource. Nothing else, perhaps, distinguishes effective executives as much as their tender loving care of time." – Peter Drucker (quoted in Frank)

67% of employees surveyed believe their CEOs focus too much on decisions based in short-term financial results and not enough time on decisions that create a stable, positive workplace for staff. (2016 Edelman Trust Barometer)

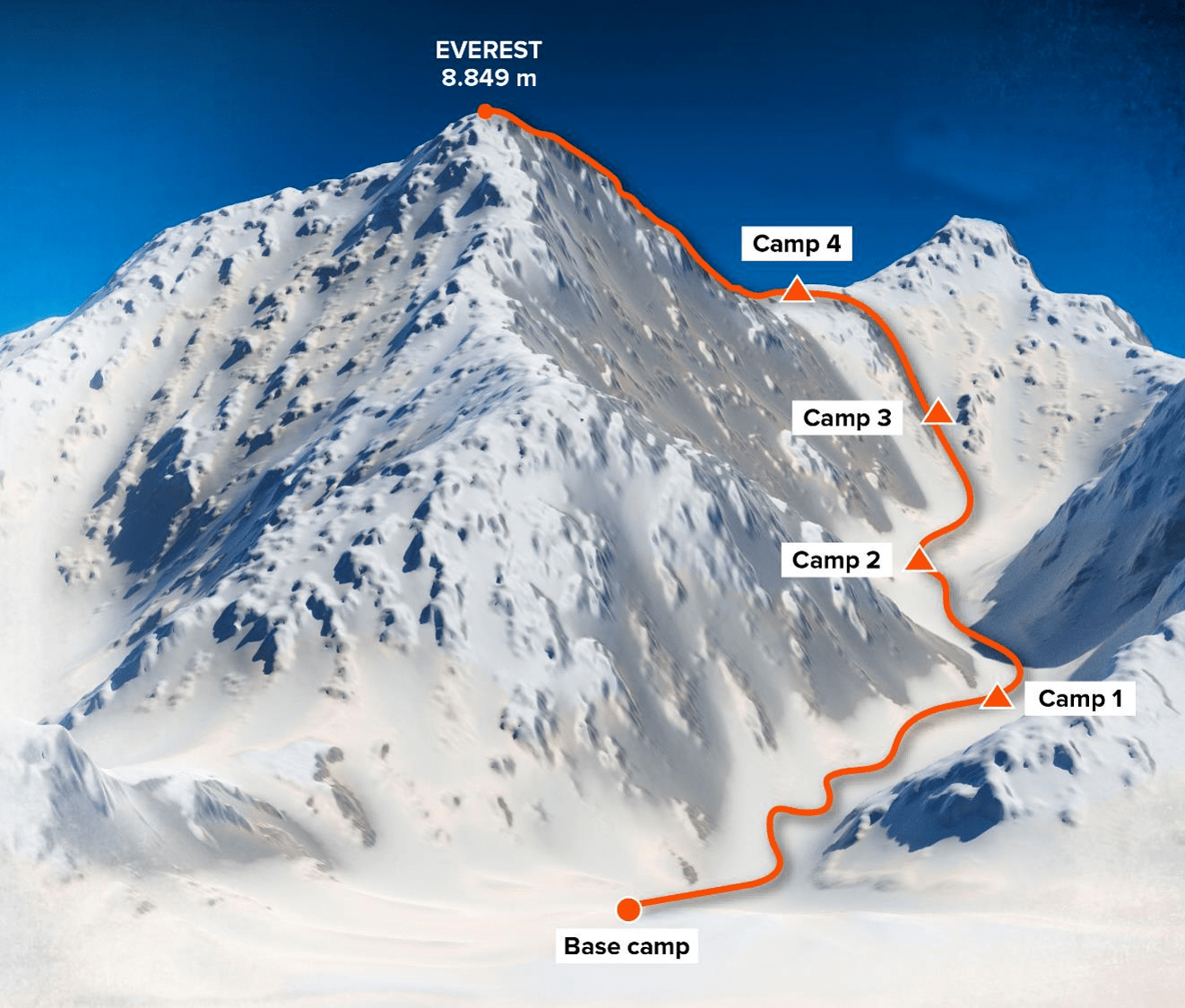

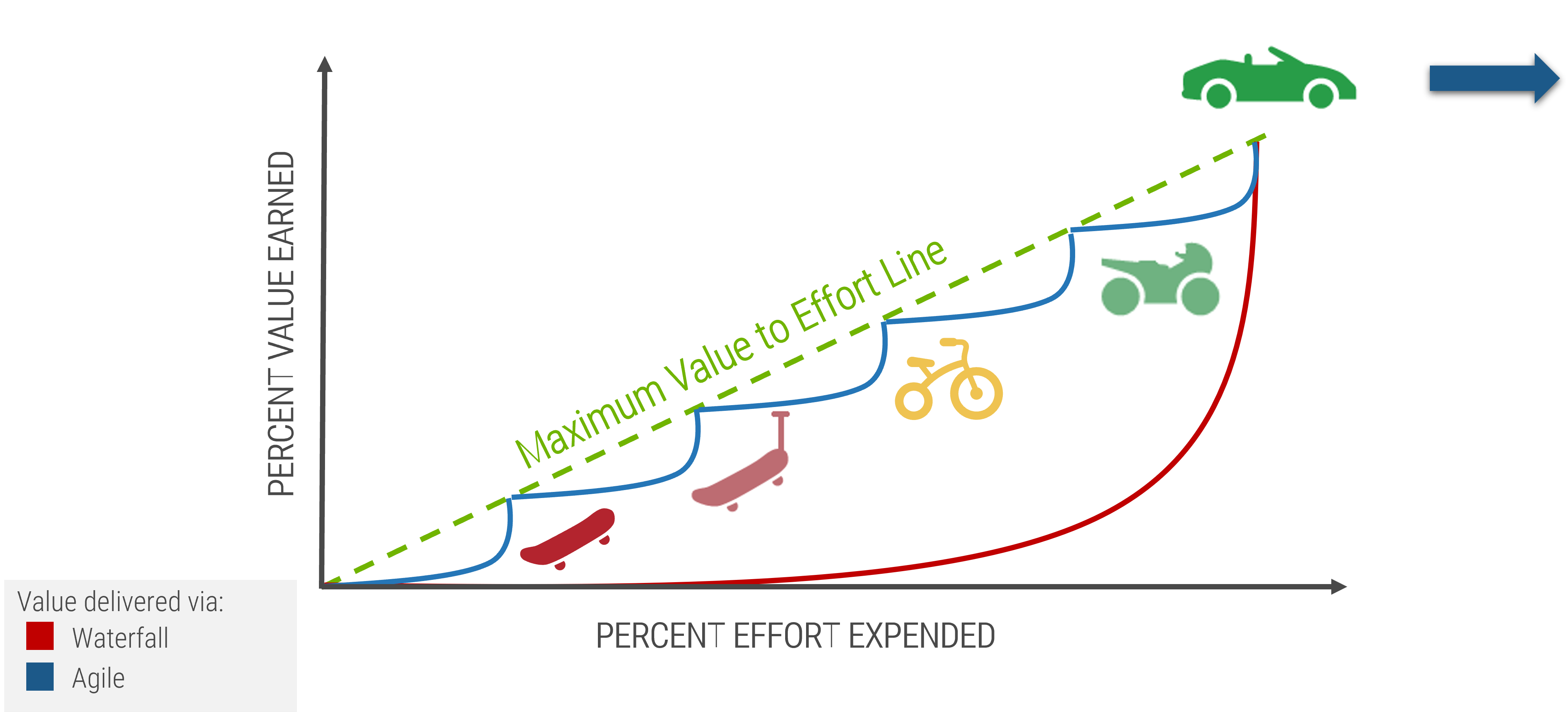

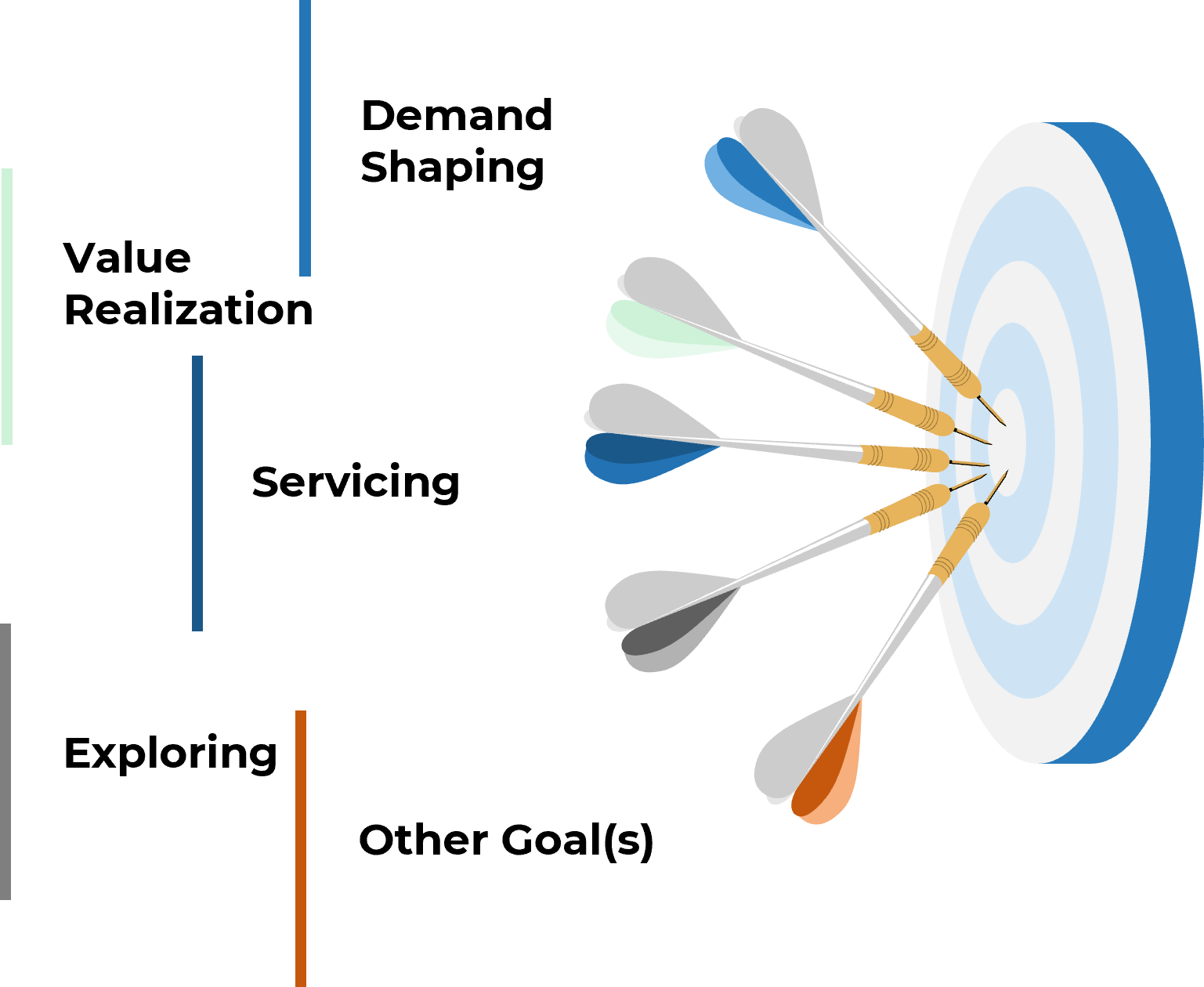

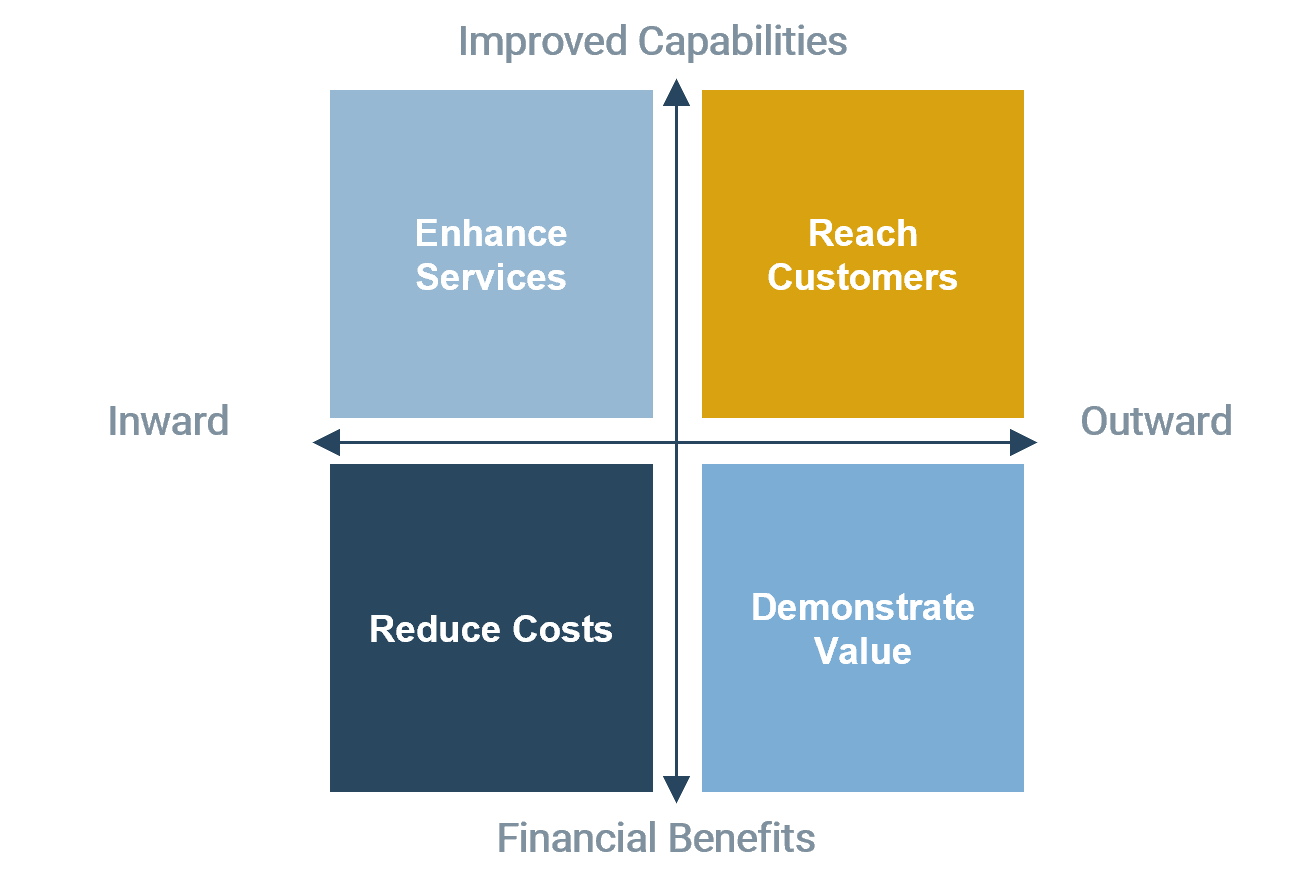

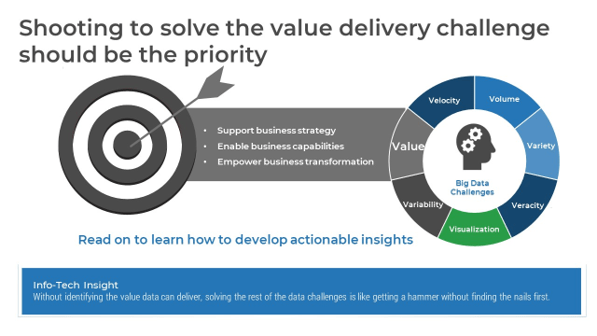

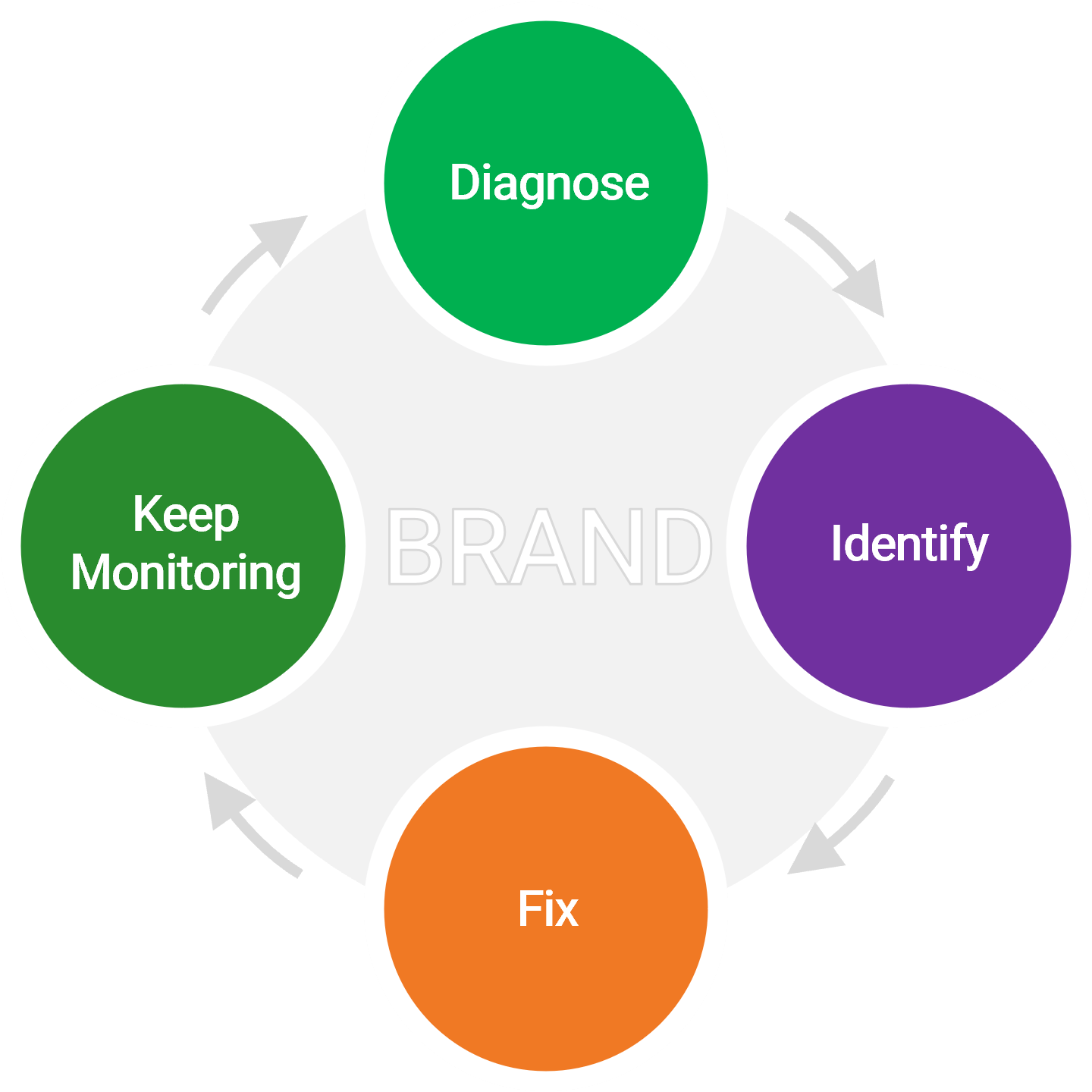

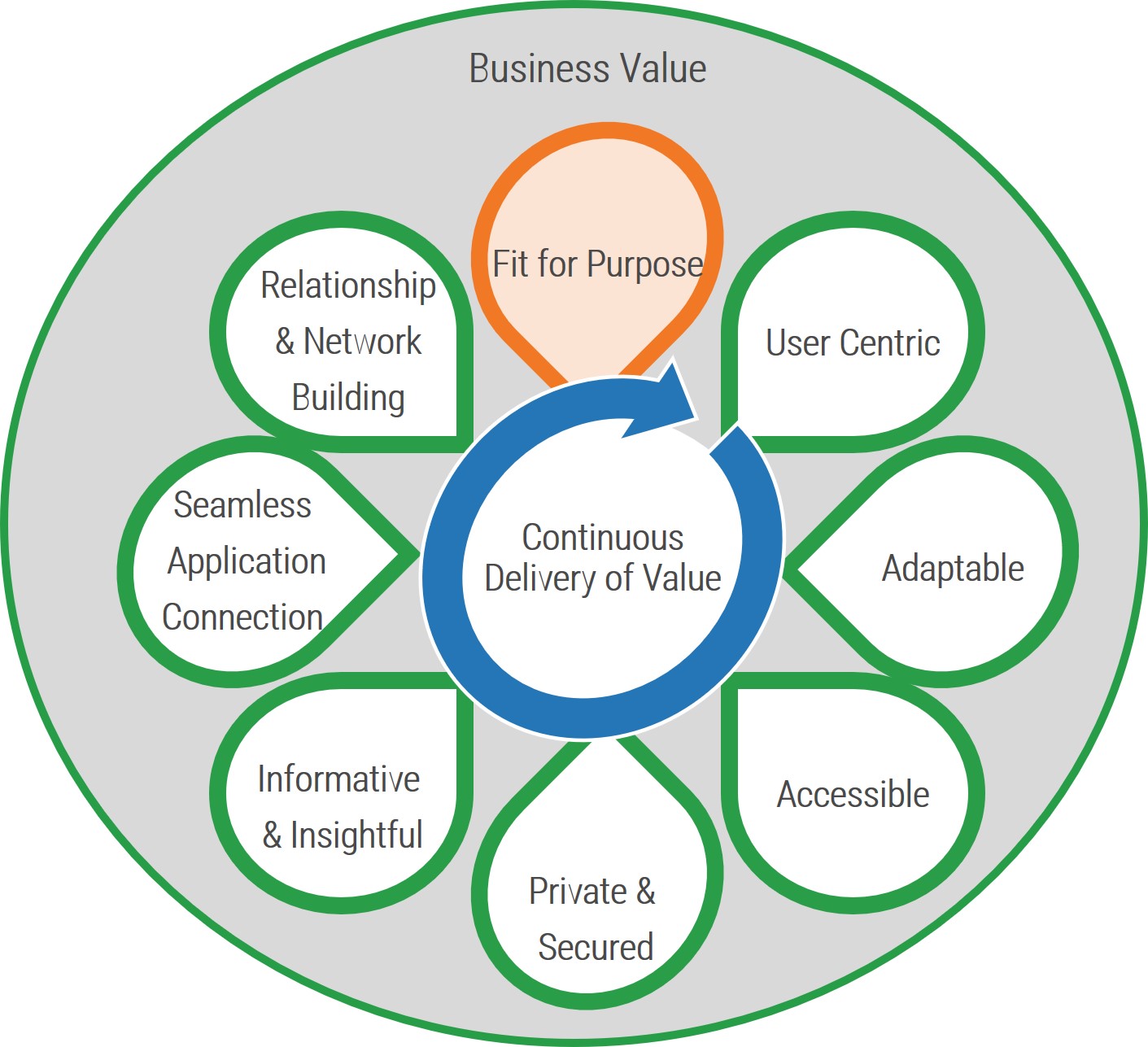

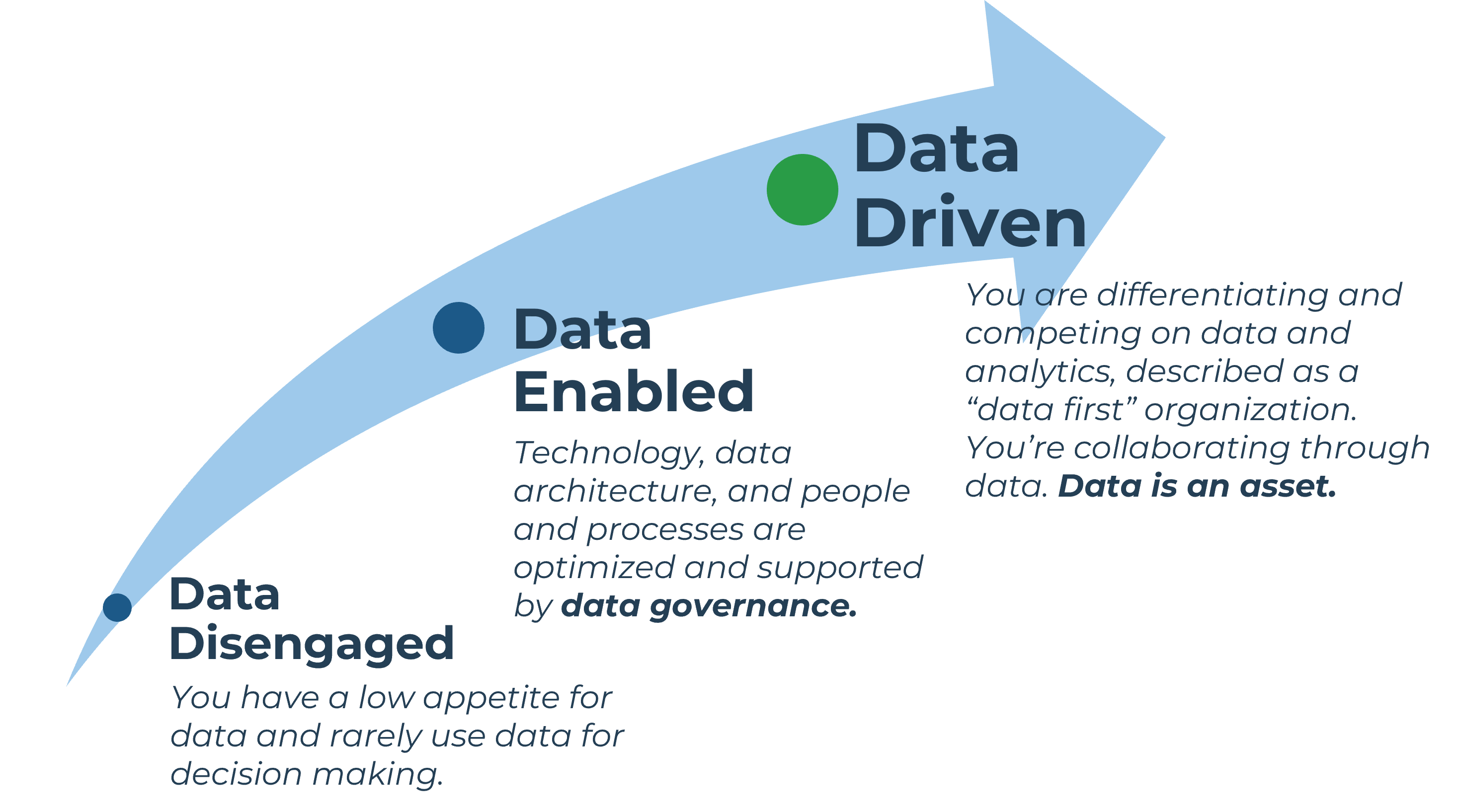

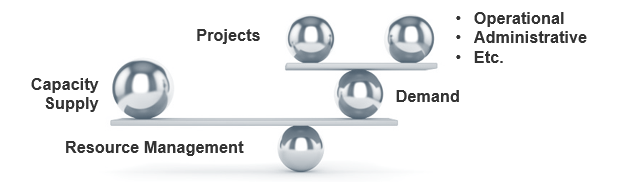

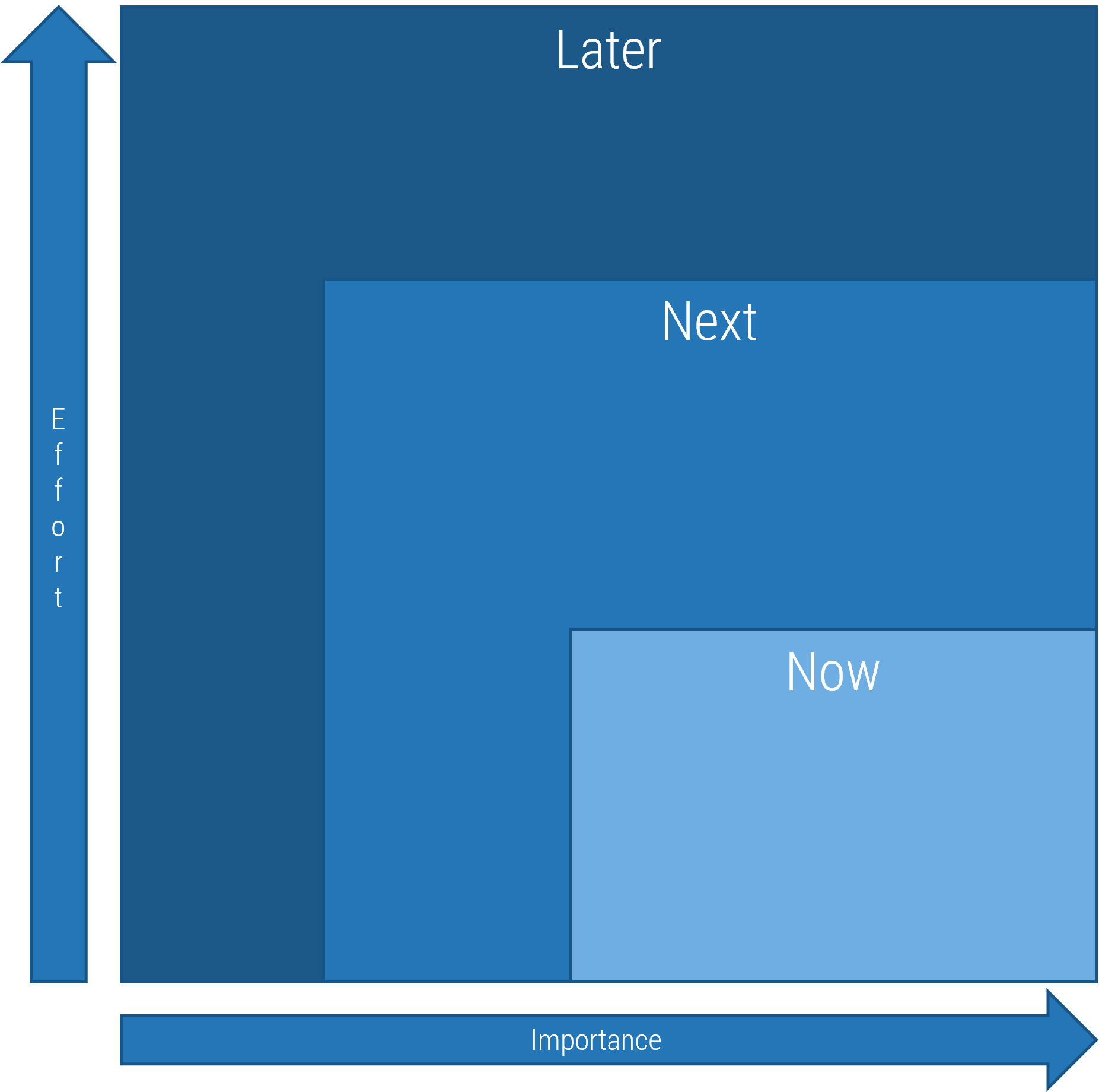

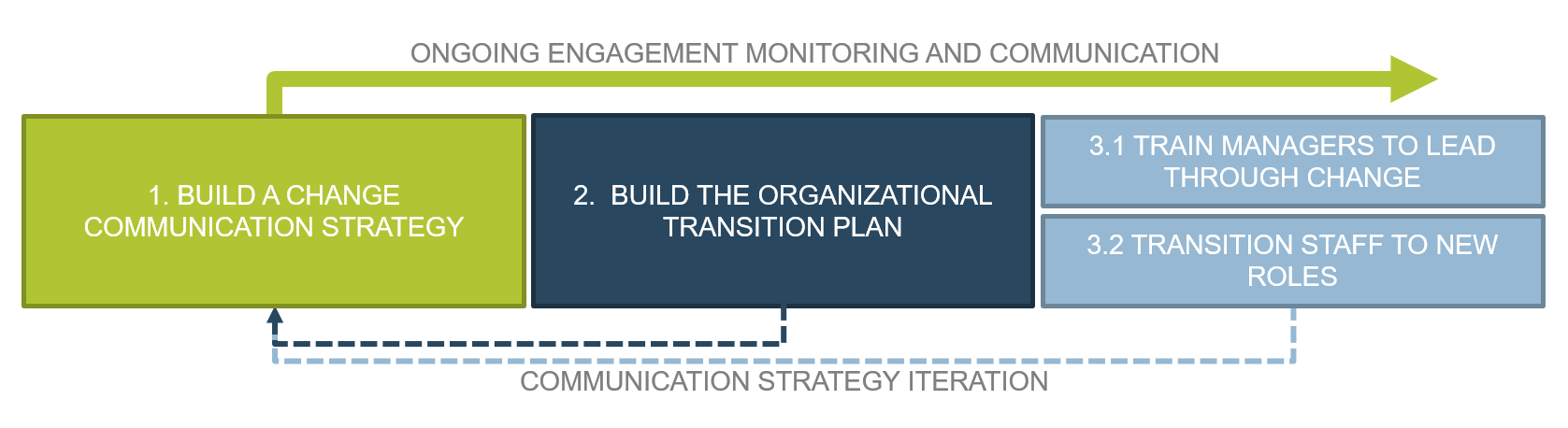

Bring balance to supply and demand with realistic resource management practices

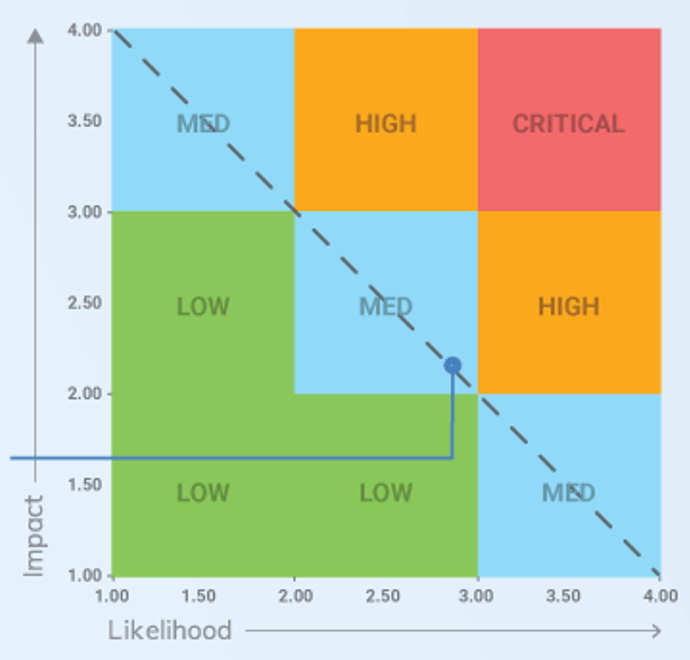

Use Info-Tech’s approach to resource management to capture an accurate view of where your time goes and achieve sustained visibility into your capacity for new projects.

Realistic project resource management starts by aligning demand with capacity, and then developing tactics to sustain alignment, even in the chaos of our fast-paced, rapidly changing, interruption-driven project environments.

This blueprint will help you develop practices to promote and maintain accurate resourcing data, while developing tactics to continually inform decision makers’ assumptions about how much capacity is realistically available for project work.

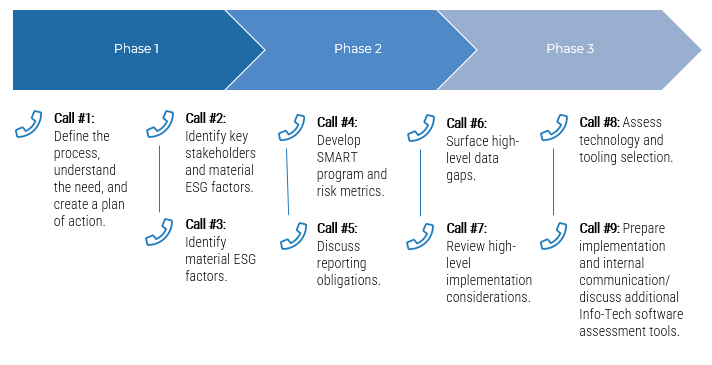

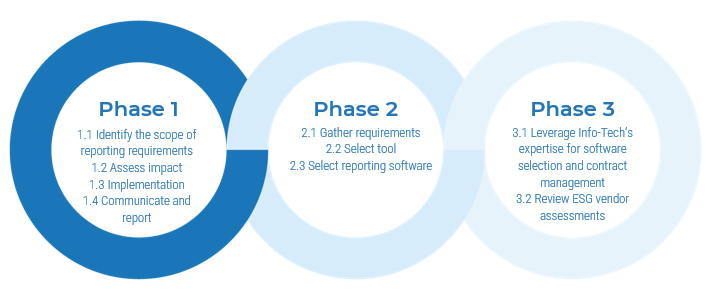

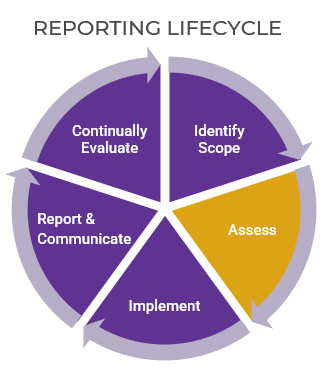

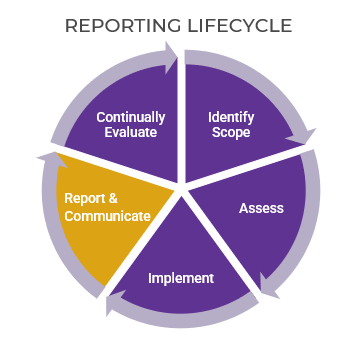

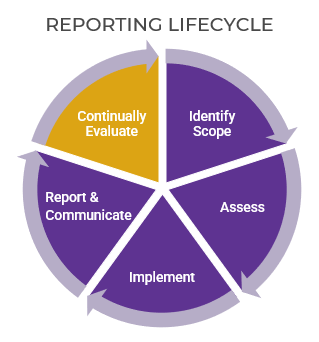

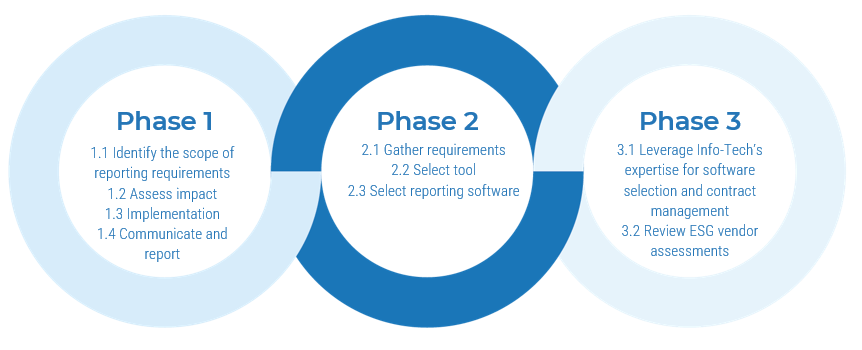

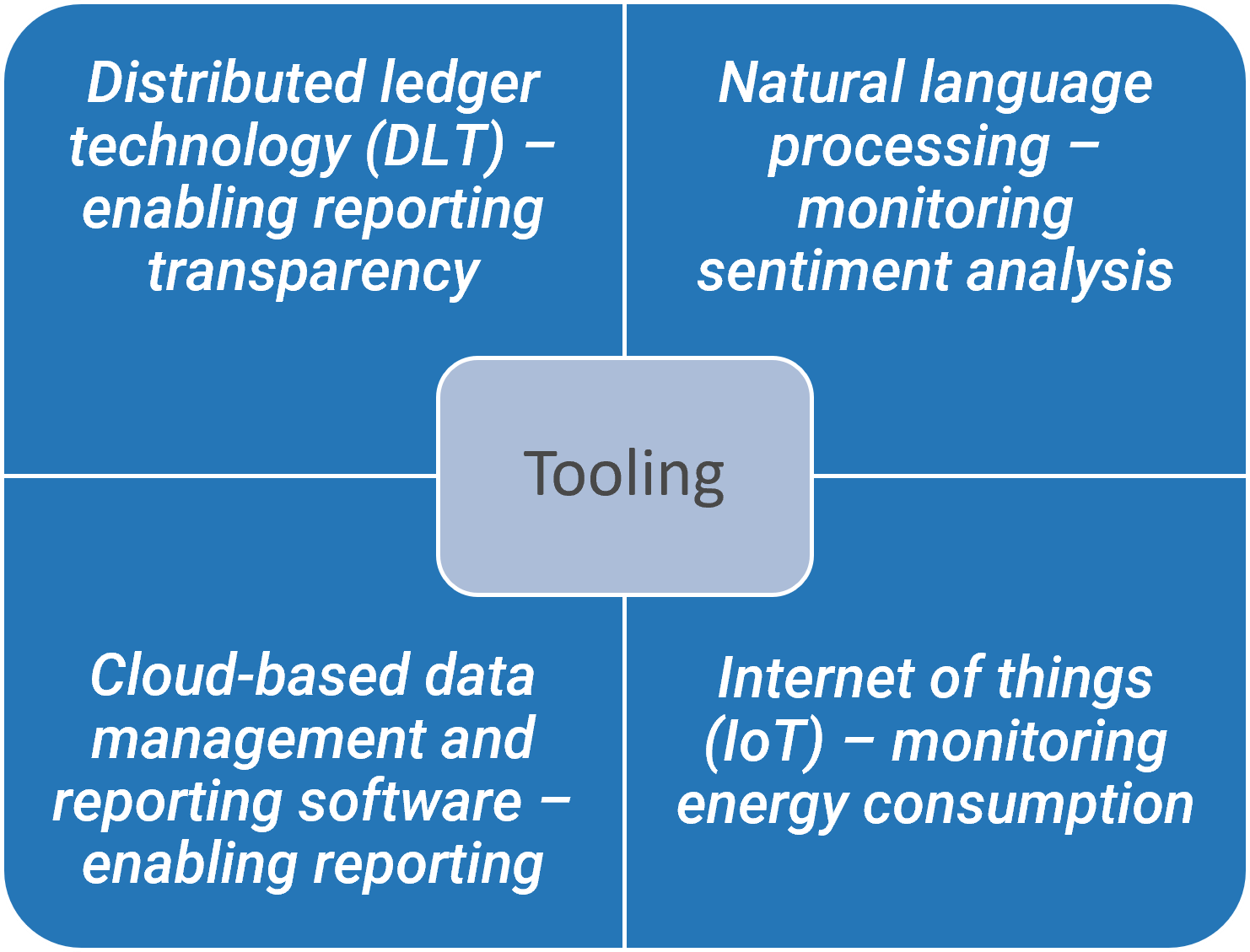

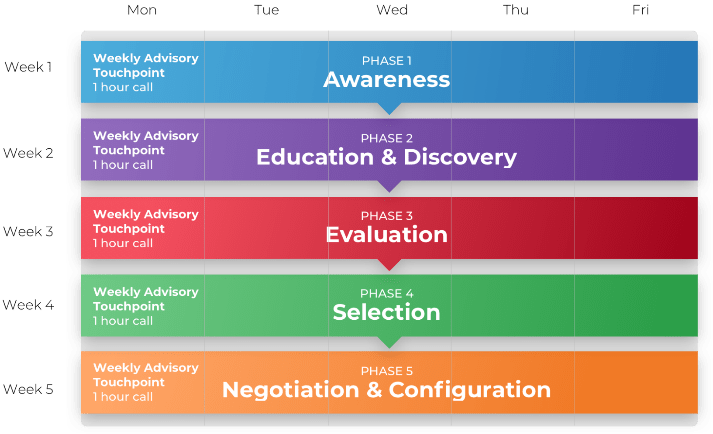

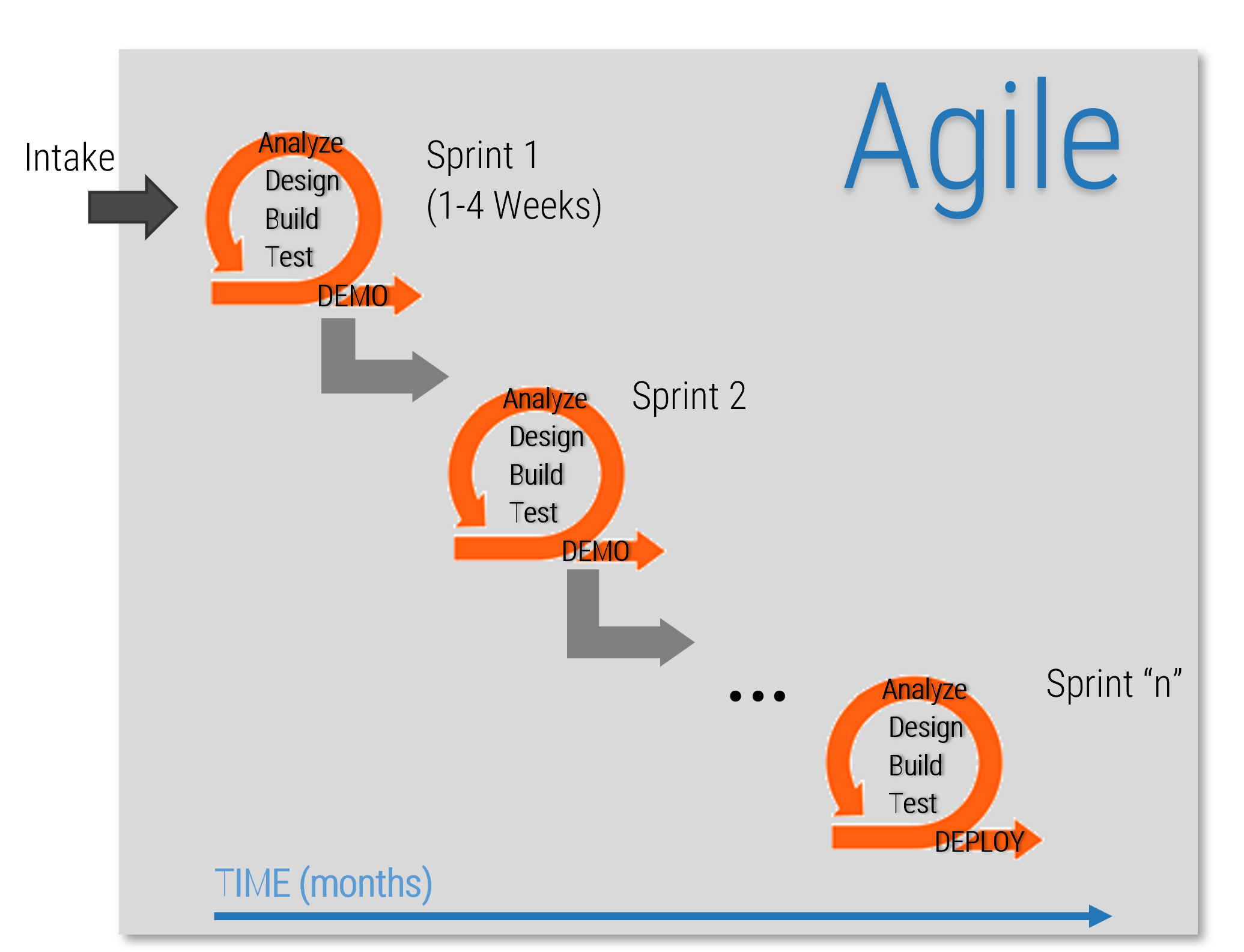

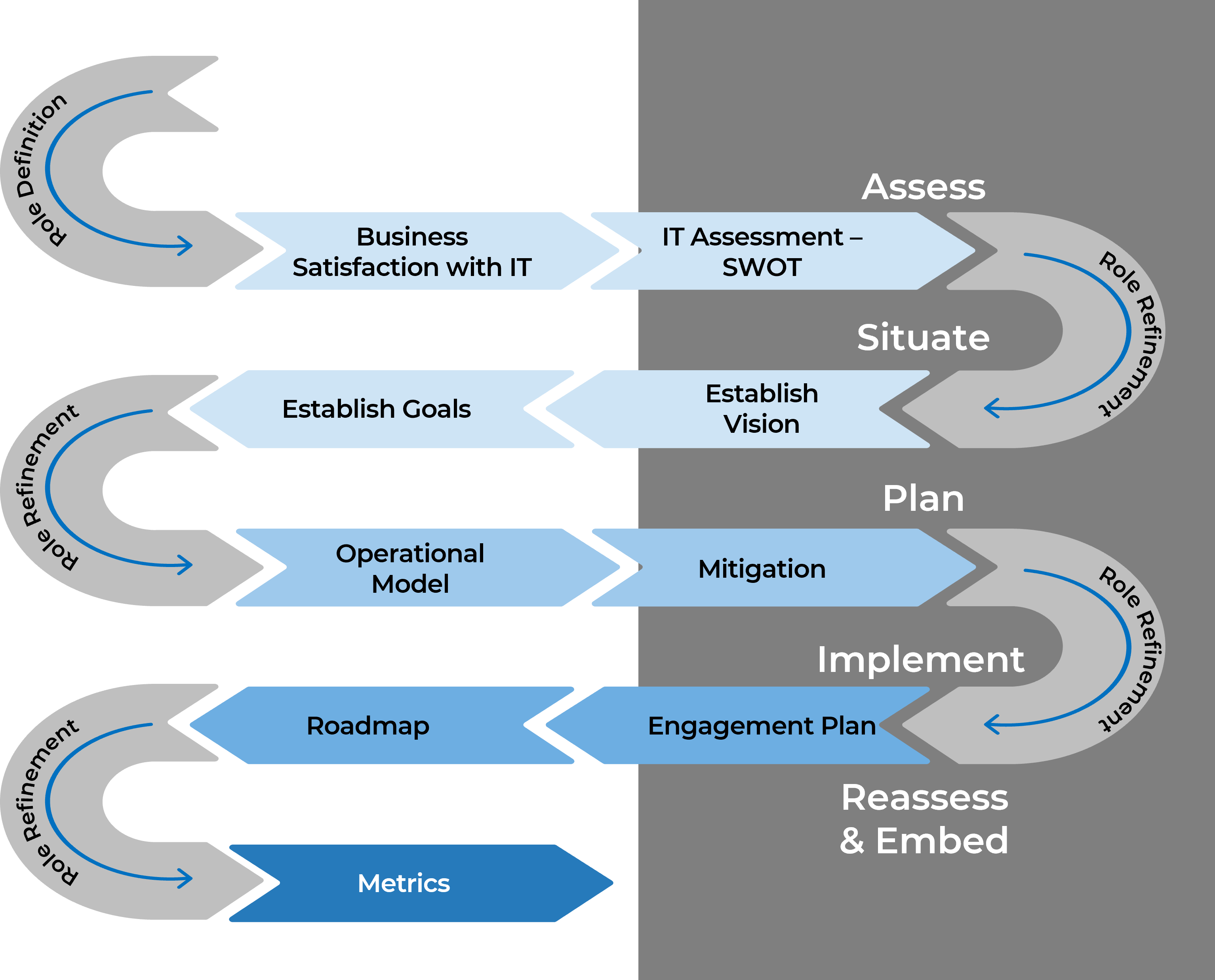

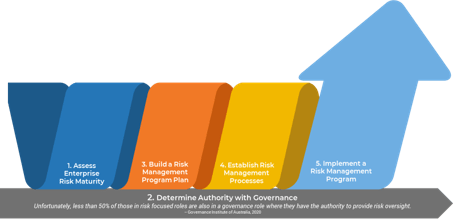

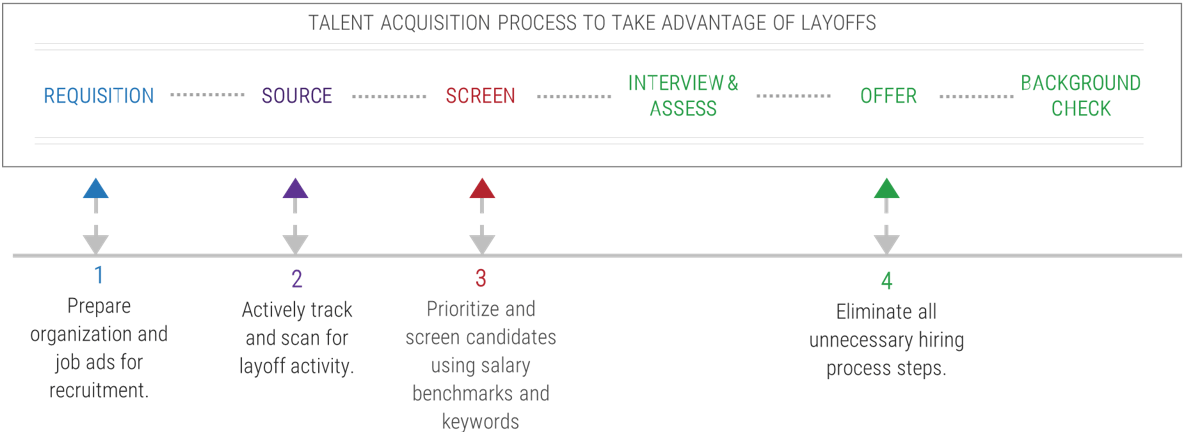

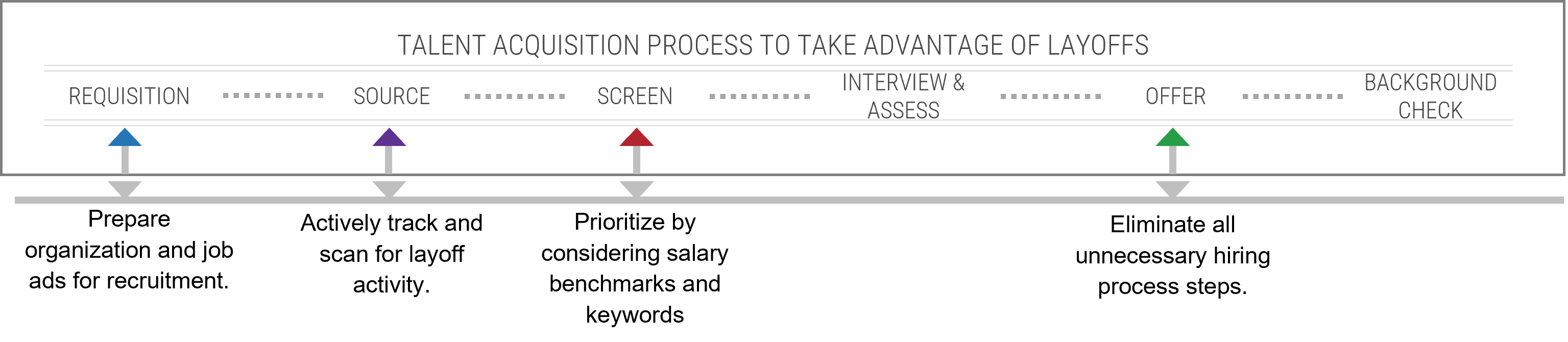

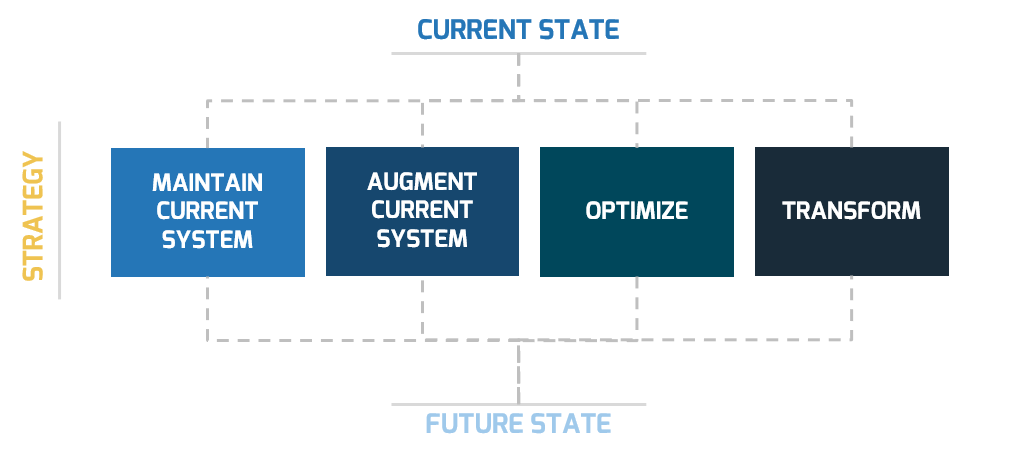

This research follows a three-phase approach to sustainable practices:

- Take Stock of Organizational Supply and Demand

- Design a Realistic Resource Management Process

- Implement Sustainable Resource Management Practices

Info-Tech’s three-phase framework is structured around a practical, tactical approach to resource management. It’s not about what you put together as a one-time snapshot. It’s about what you can and will maintain every week, even during a crisis. When you stop maintaining resource management data, it’s nearly impossible to catch up and you’re usually forced to start fresh.

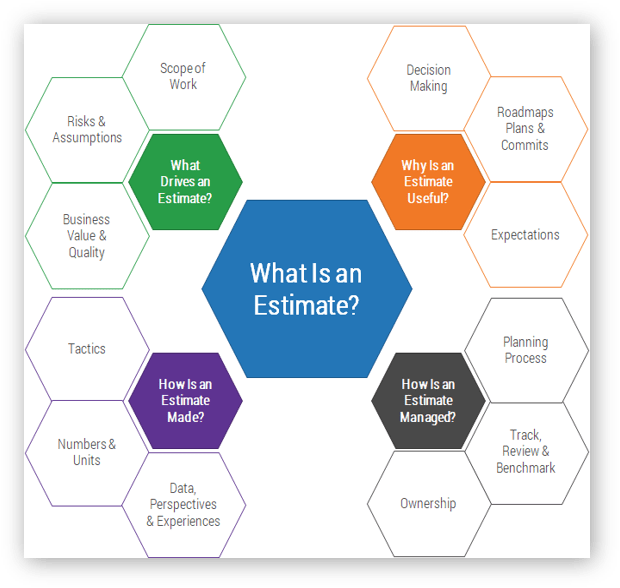

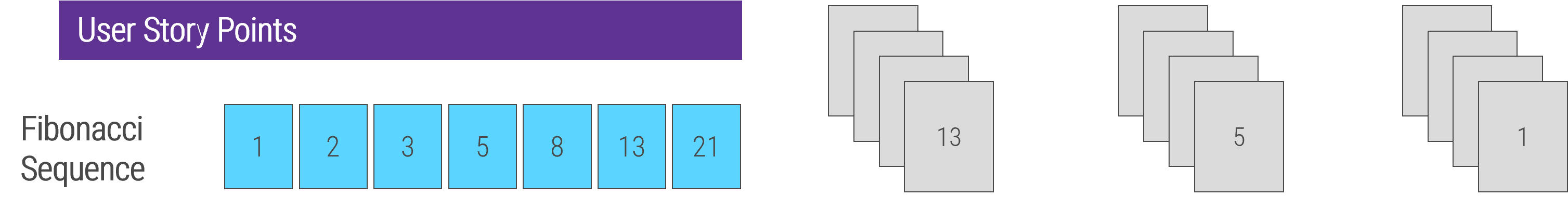

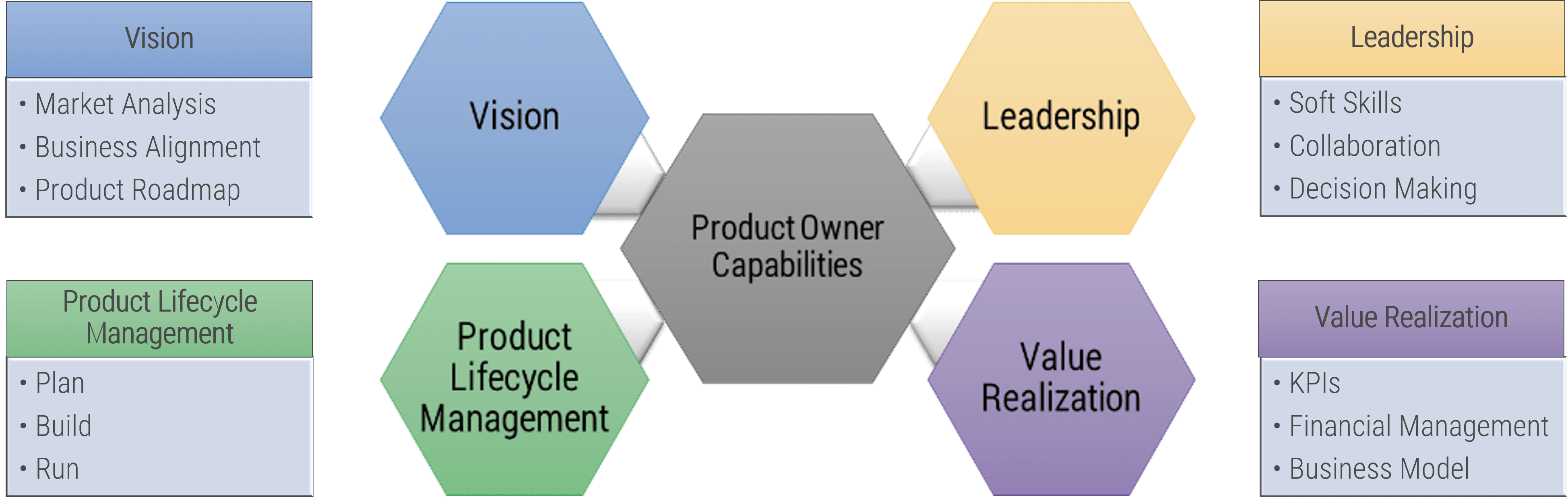

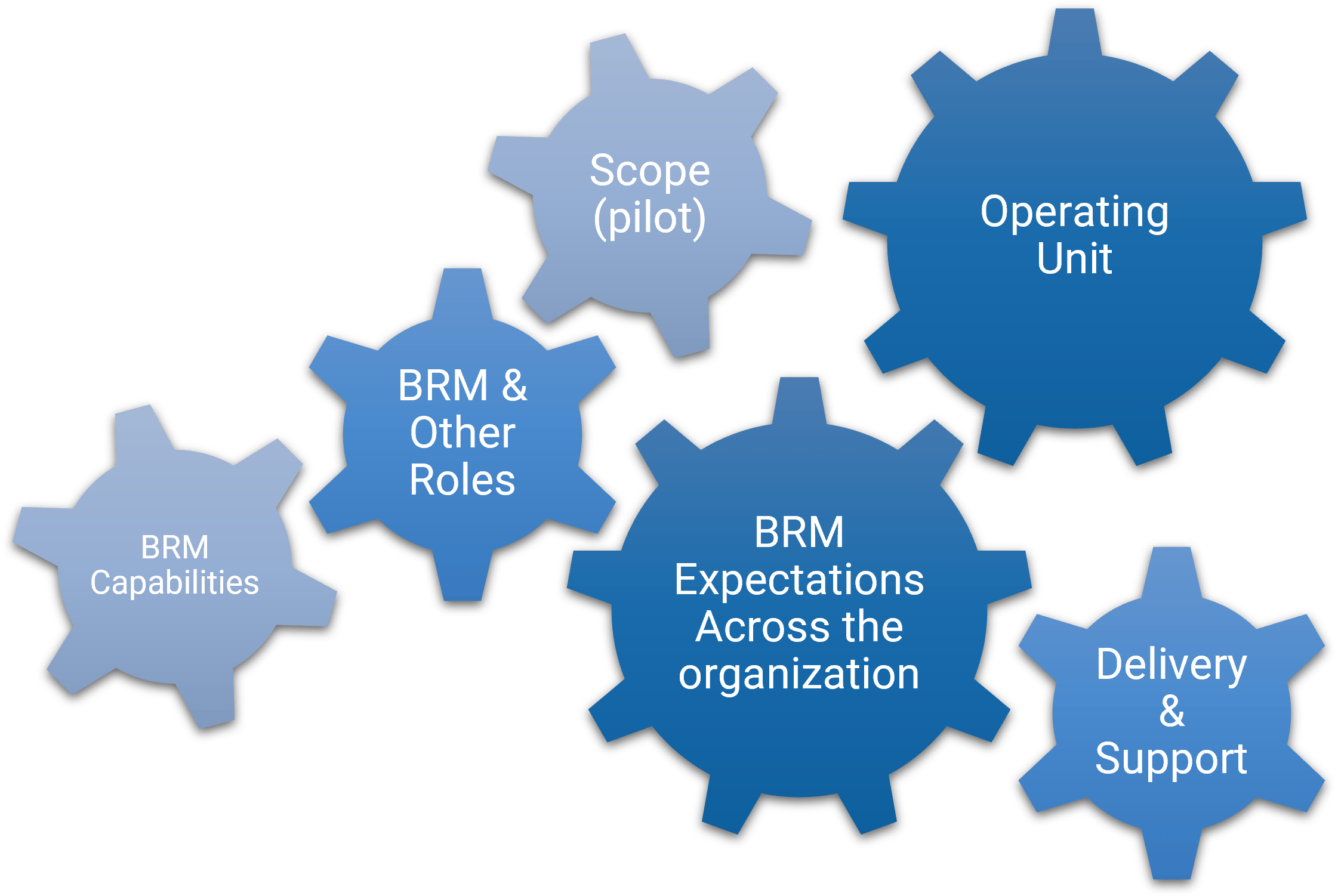

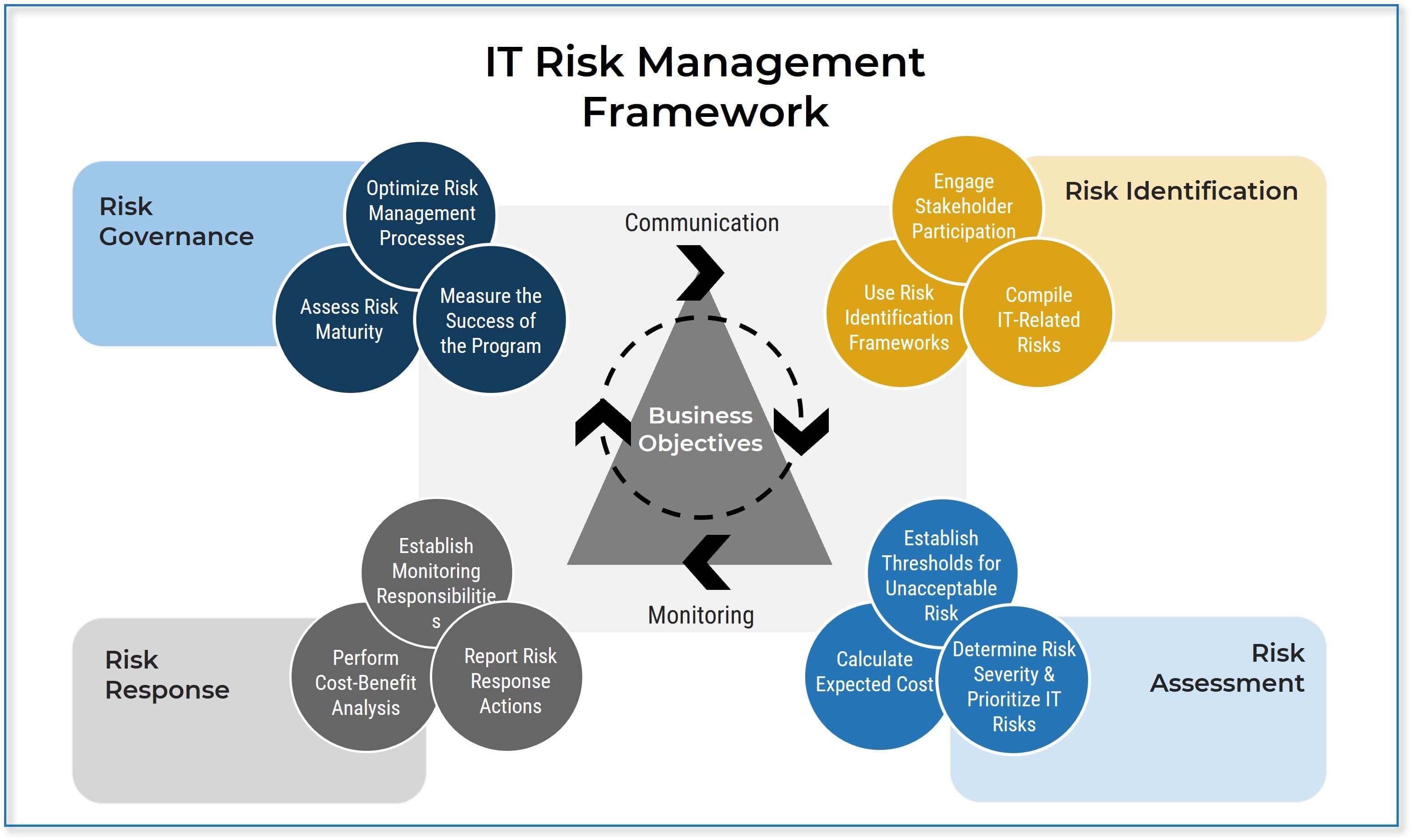

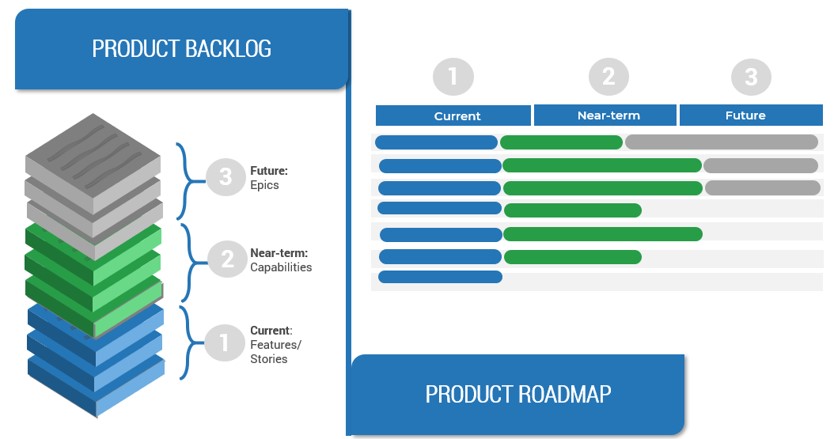

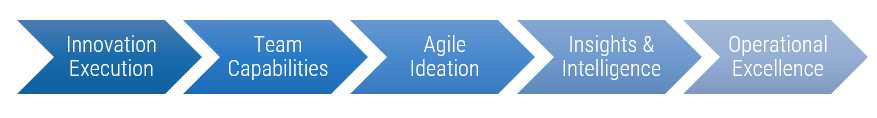

Info-Tech’s approach is rooted in our seven dimensions of resource management

Action the decision points across Info-Tech’s seven dimensions to ensure your resource management process is guided by realistic data and process goals.

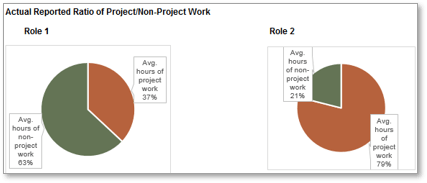

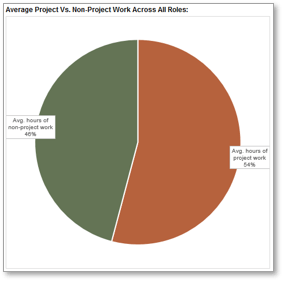

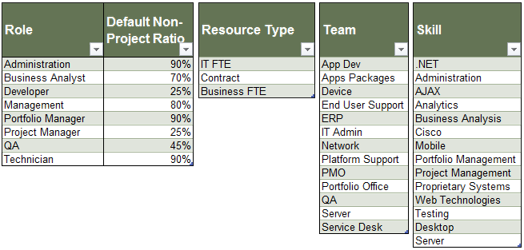

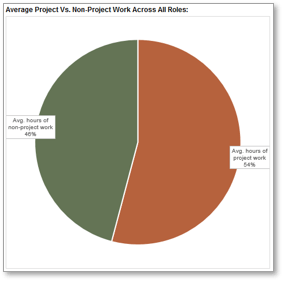

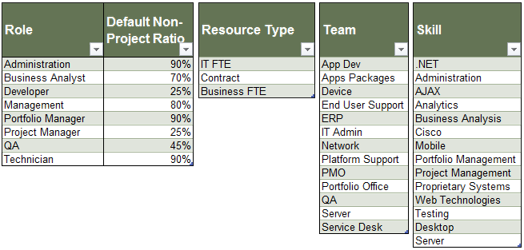

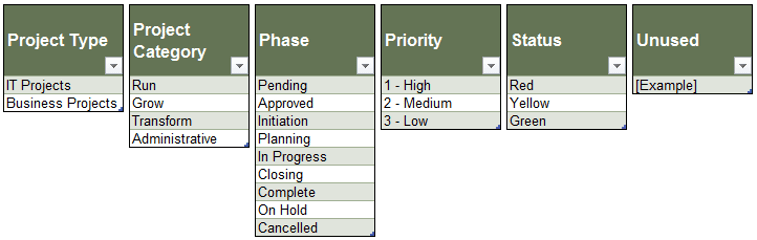

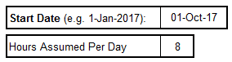

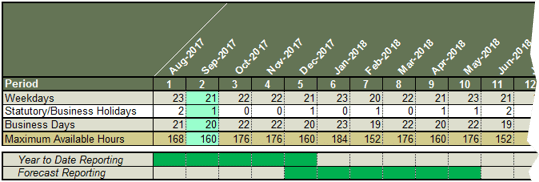

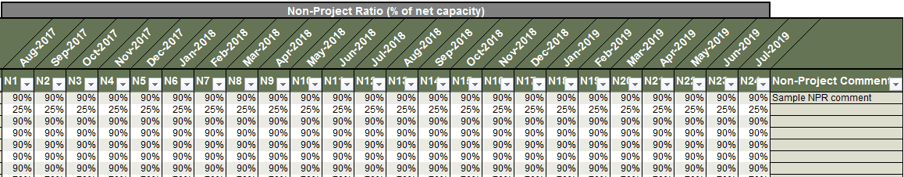

Default project vs. non-project ratio

How much time is available for projects once non-project demands are factored in?

Reporting frequency

How often is the allocation data verified, reconciled, and reported for use?

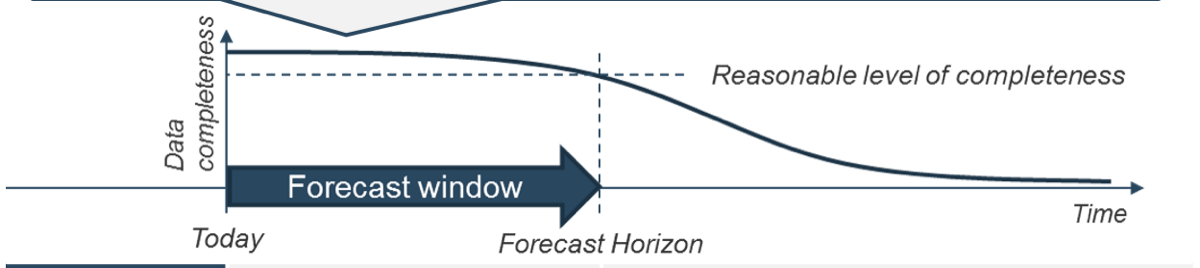

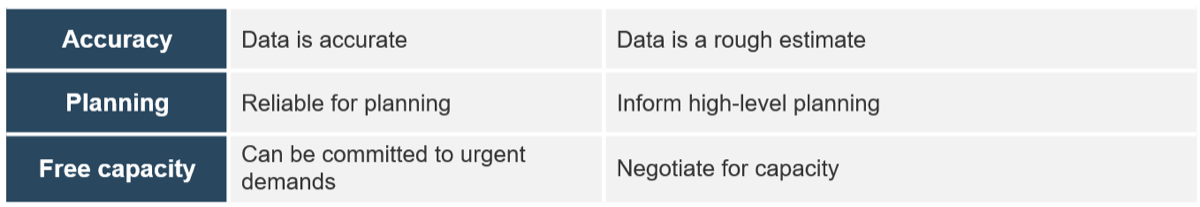

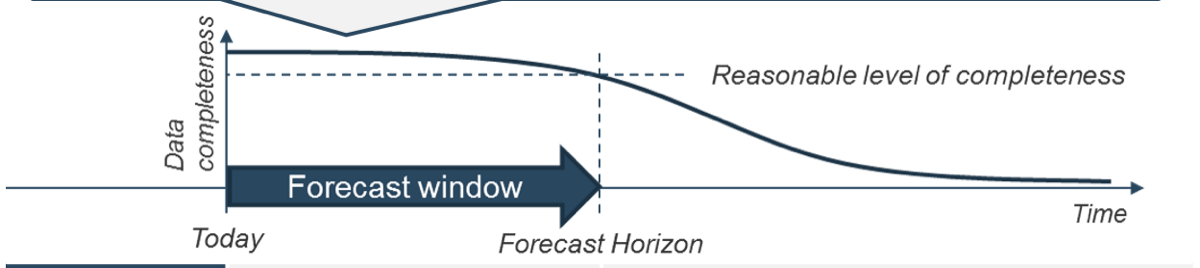

Forecast horizon

How far into the future can you realistically predict resource supply?

Scope of allocation

To whom is time allocated?

Allocation cadence

How long is each allocation period?

Granularity of time allocation

What’s the smallest unit of time to allocate?

Granularity of work assignment

What is time allocated to?

This blueprint will help you make the right decisions for your organization across each of these dimensions to ensure your resource management practices match your current process maturity levels.

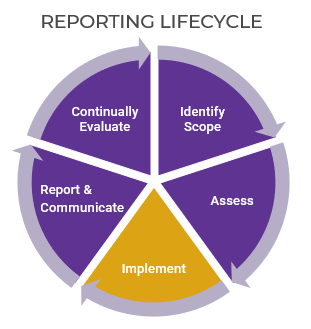

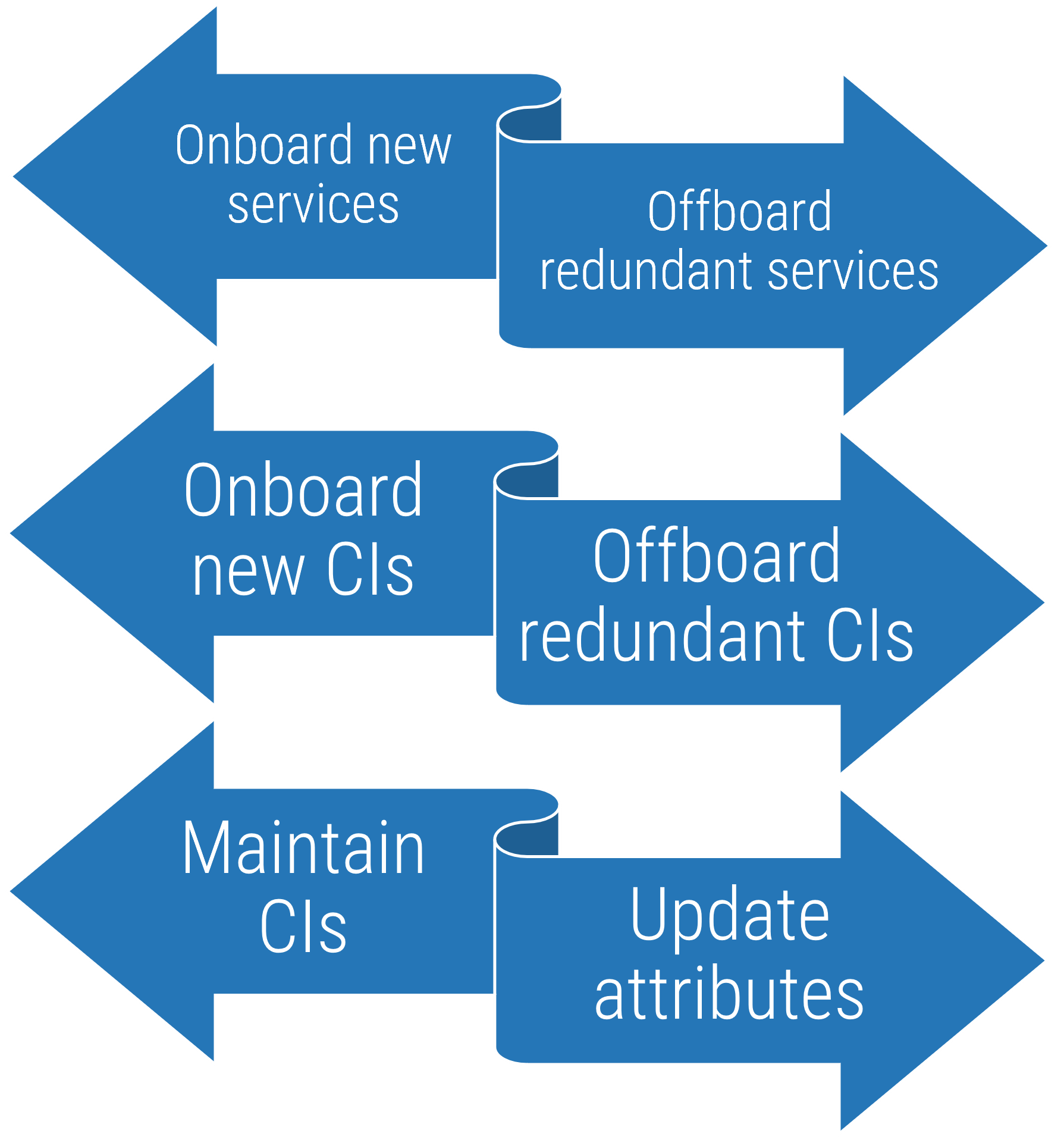

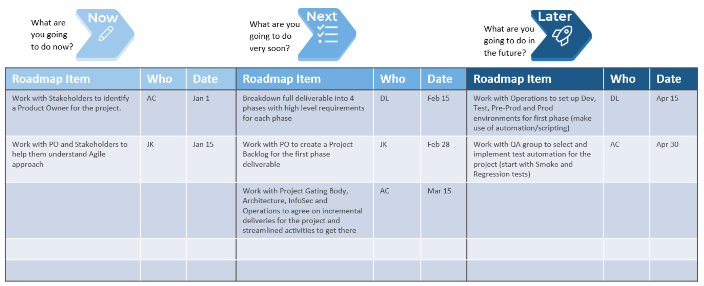

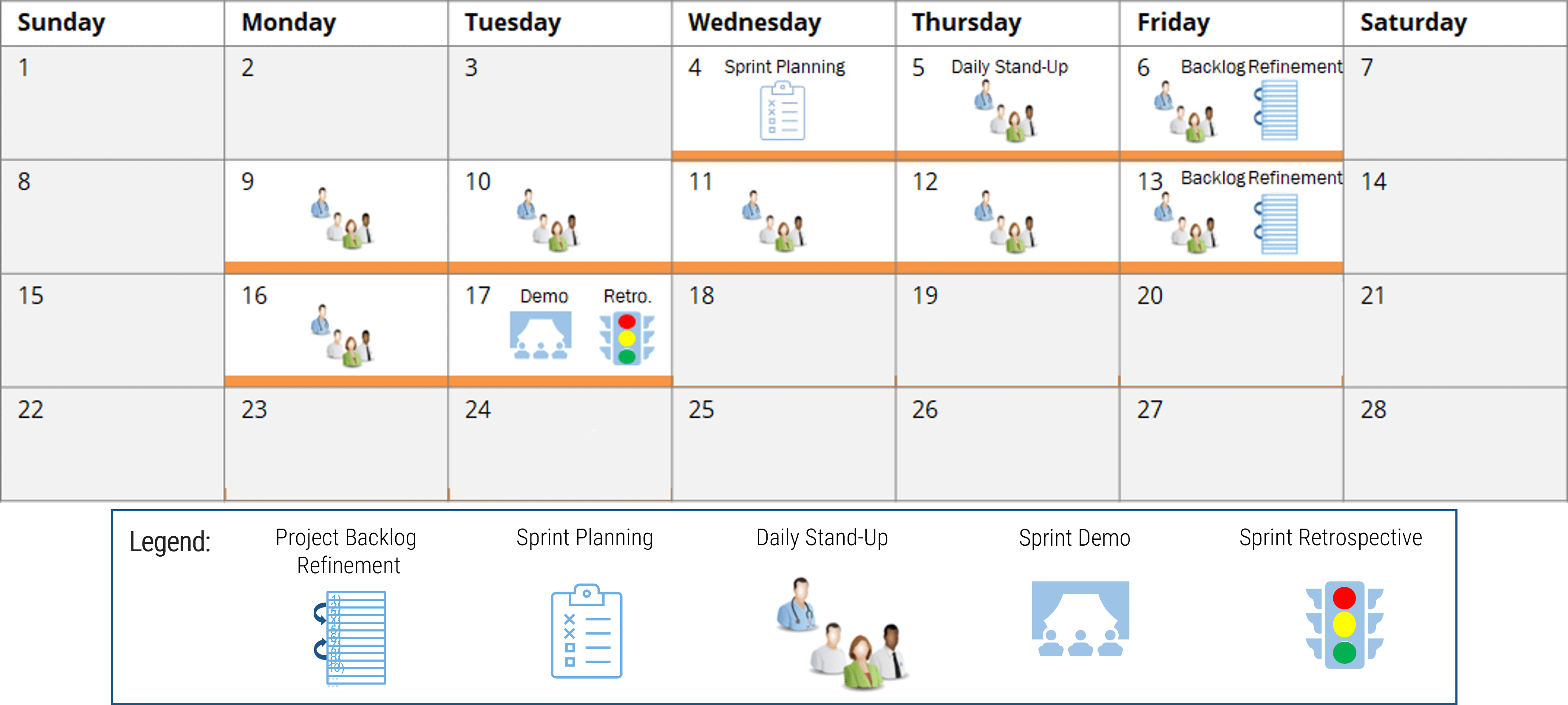

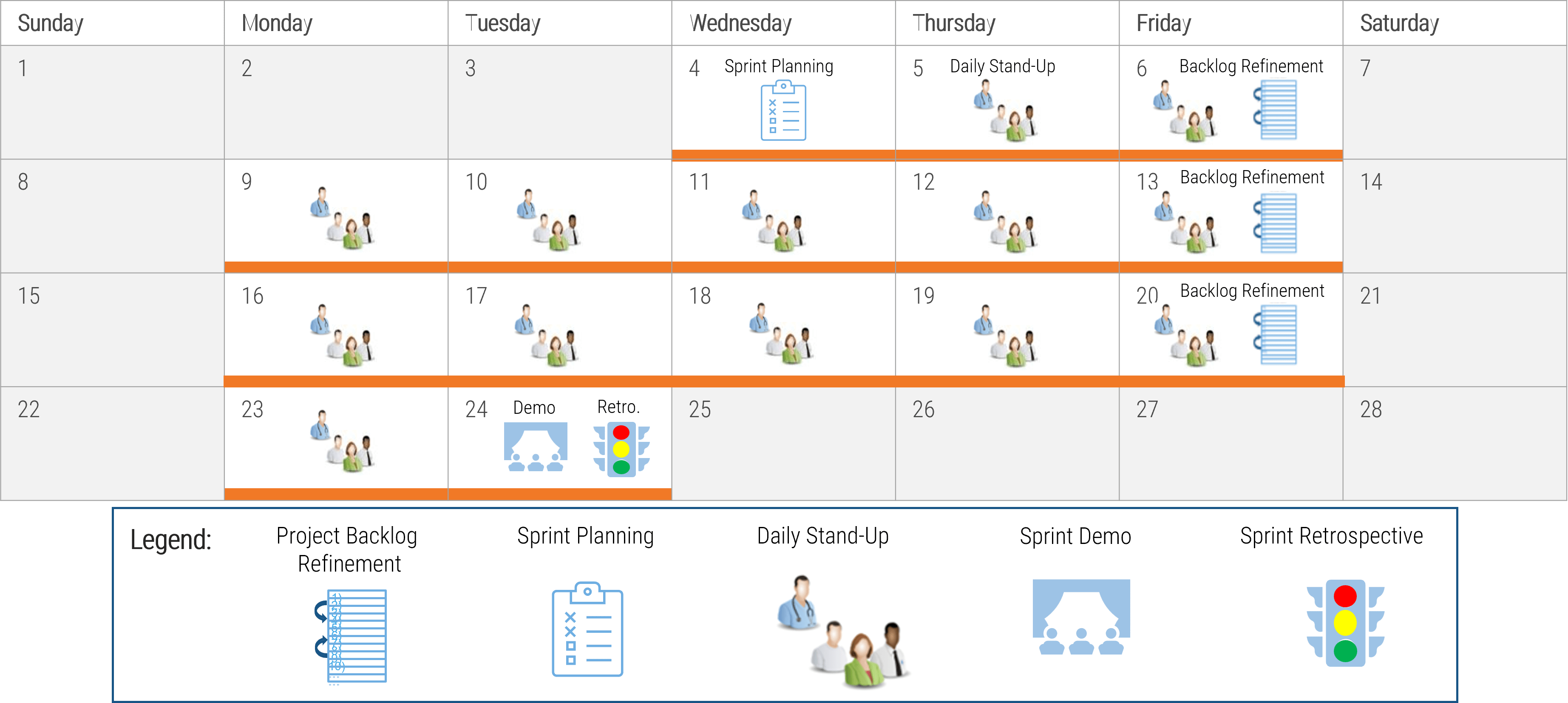

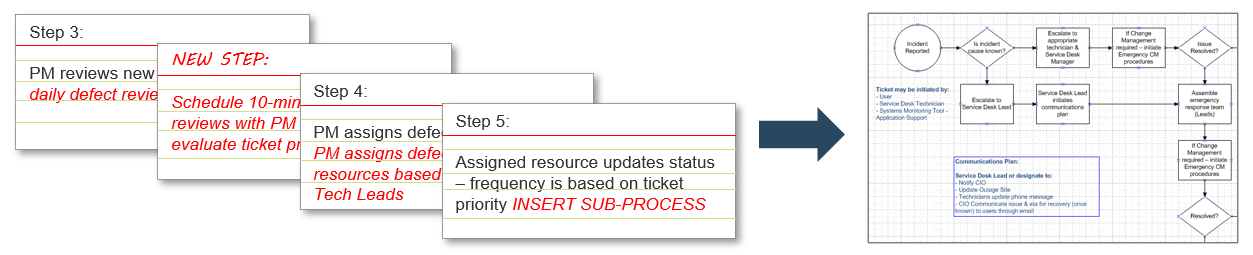

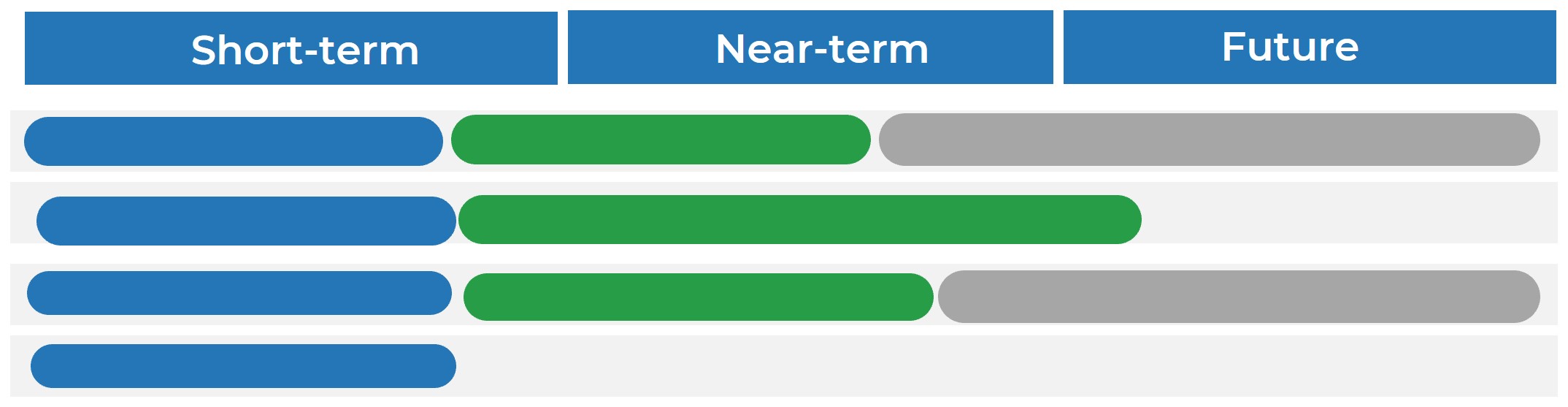

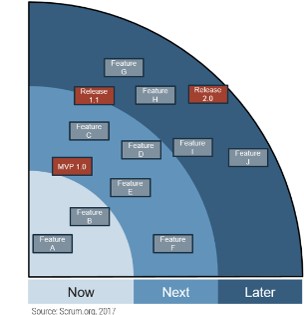

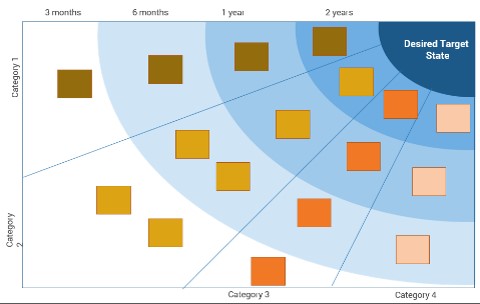

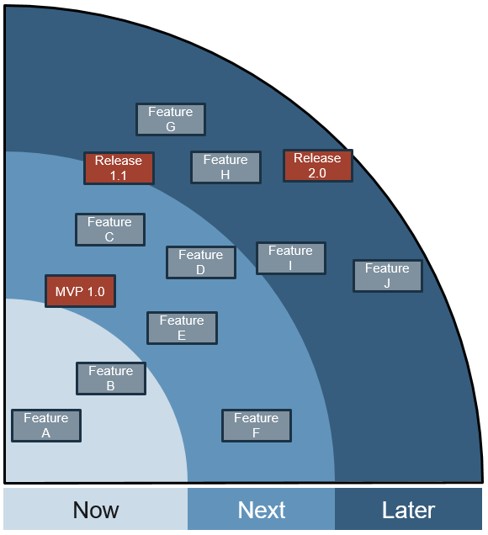

Once your framework is defined, we’ll equip you with a tactical plan to help keep supply and demand continually balanced

This blueprint will help you customize a playbook to ensure your allocations are perpetually balanced week after week, month after month.

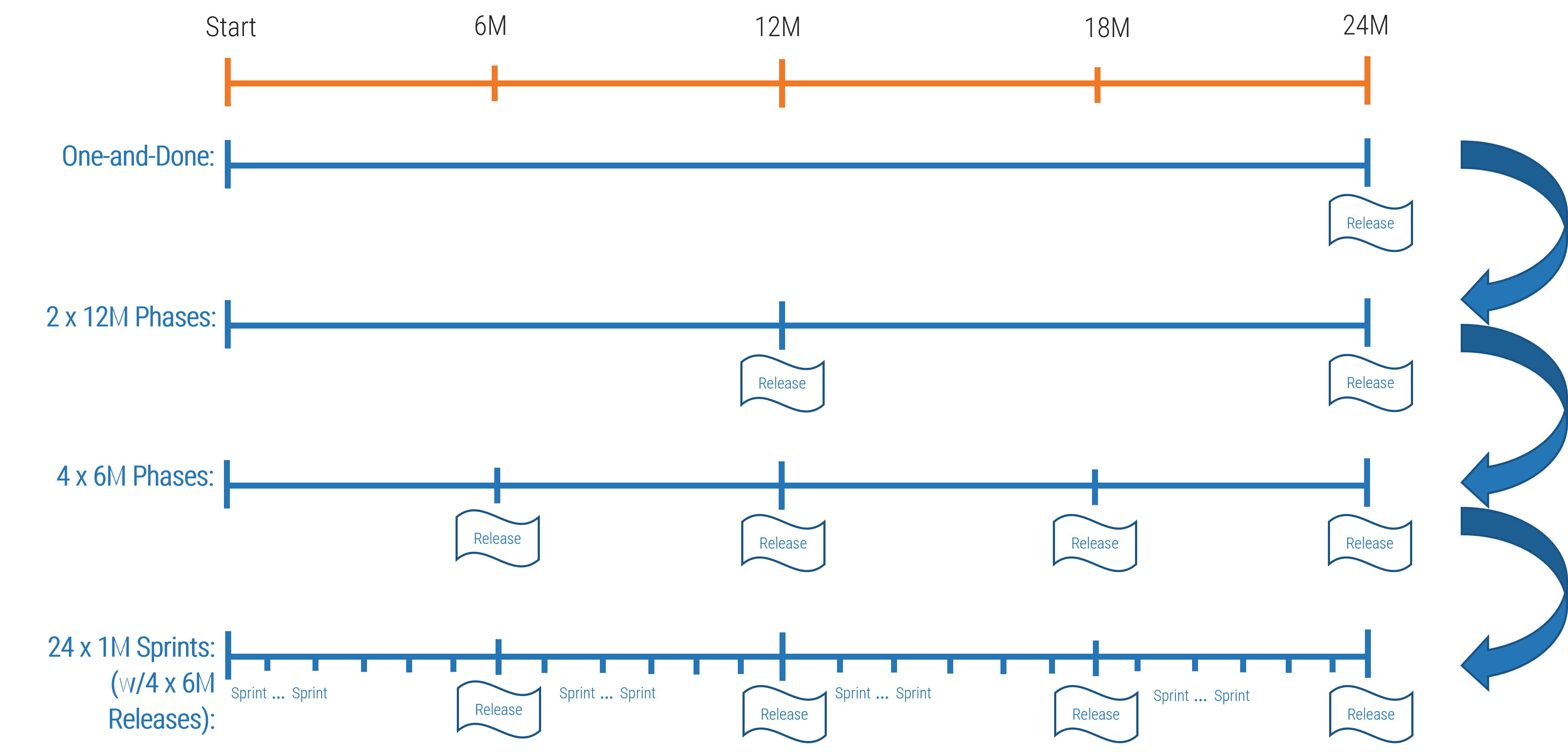

Developing a process is one thing, sustaining it is another.

The goal of this research isn’t just to achieve a one-time balancing of workloads and expect that this will stand the test of time.

The true test of a resource management process is how well it facilitates the flow of accurate and usable data as workloads become chaotic, and fires and crises erupt.

- Info-Tech’s approach will help you develop a playbook and a “rebalancing routine” that will help ensure your allocations remain perpetually current and balanced.

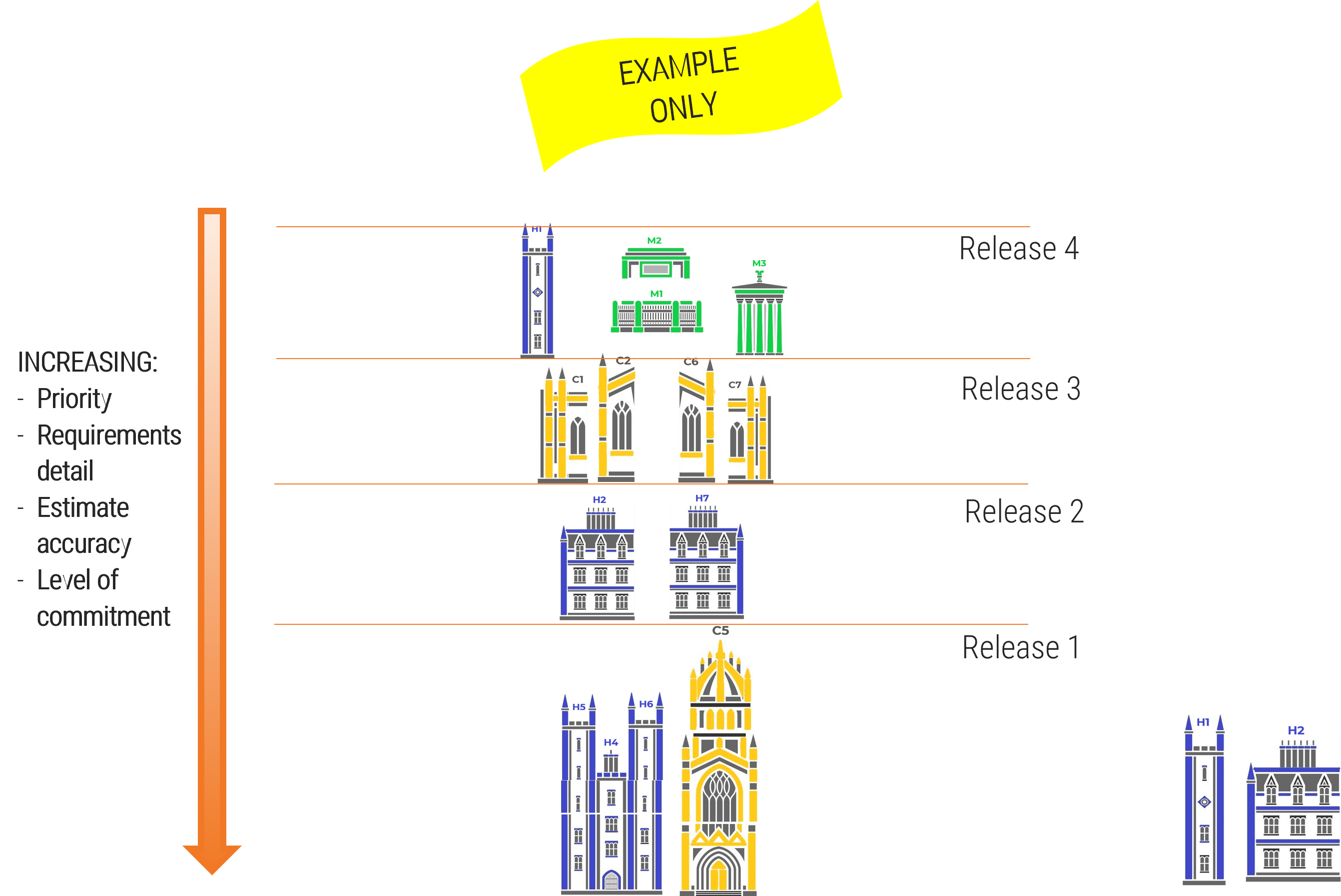

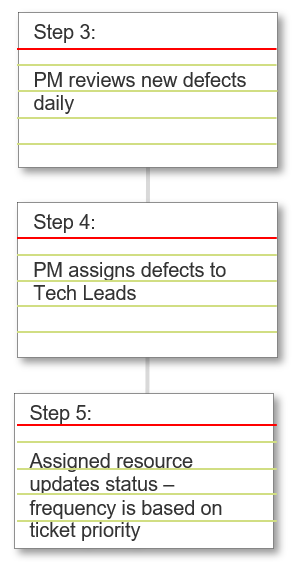

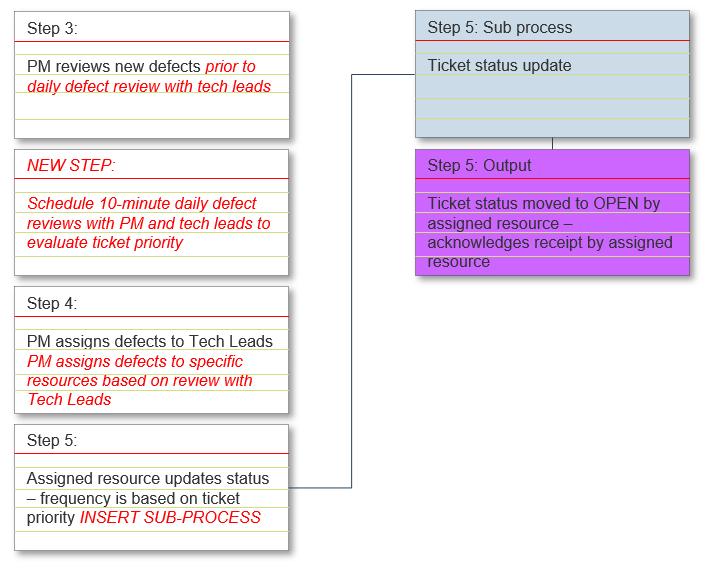

- The sample routine to the right shows you an example of what this rebalancing process will look like (customizing this process is covered in Phase 3 of the blueprint).

Sample “rebalancing” routine

- Maintain a comprehensive list of the sources of demand (i.e. document the matrix).

- Catalog the demand.

- Allocate the supply.

- Forecast the capacity to your forecast horizon.

- Identify and prepare work packages or tasks for unsatisfied demand to ensure that supply can be utilized if it becomes free.

- Reconcile any imbalance by repeating steps 1-5 on update frequency, say, weekly or monthly.

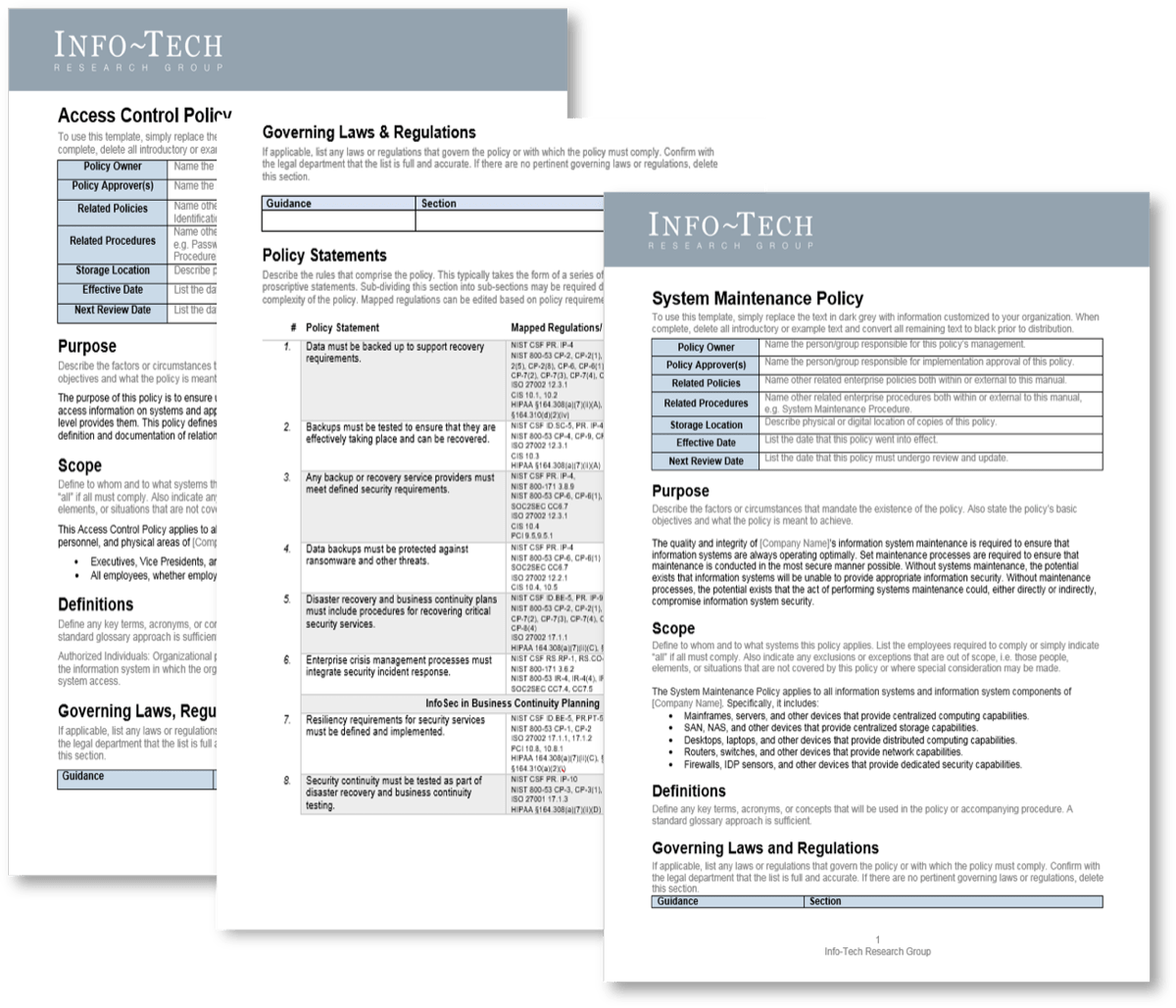

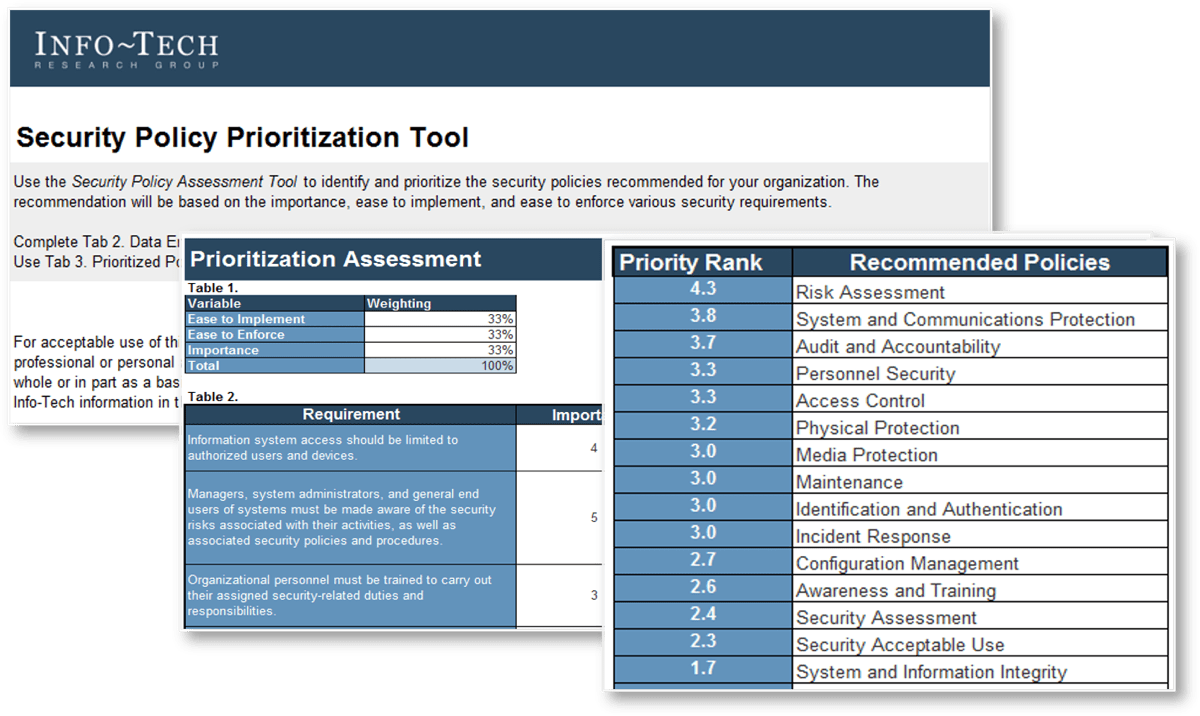

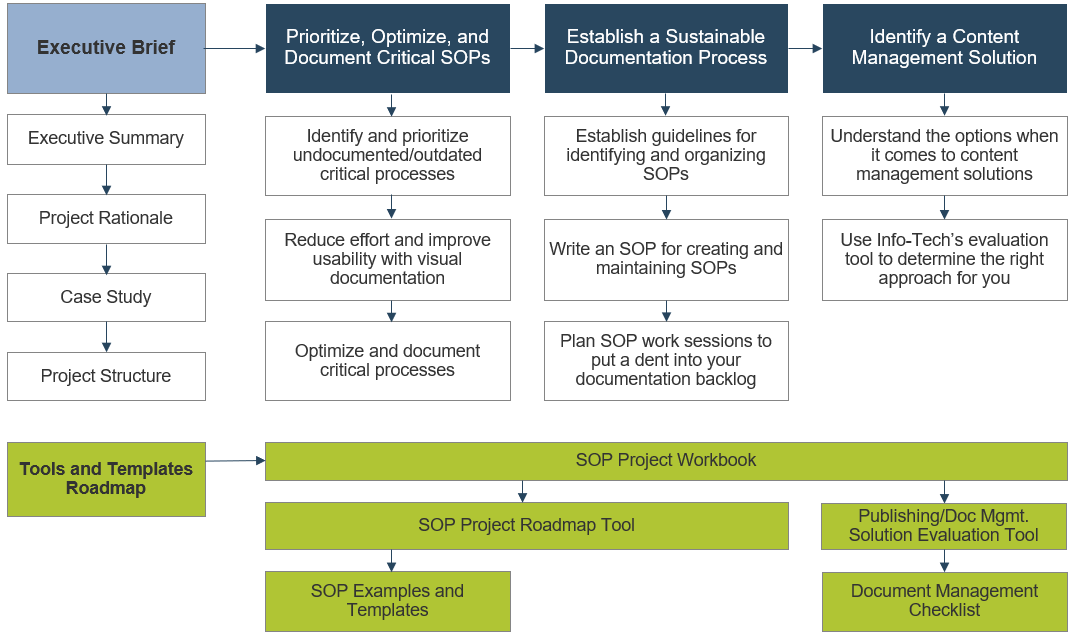

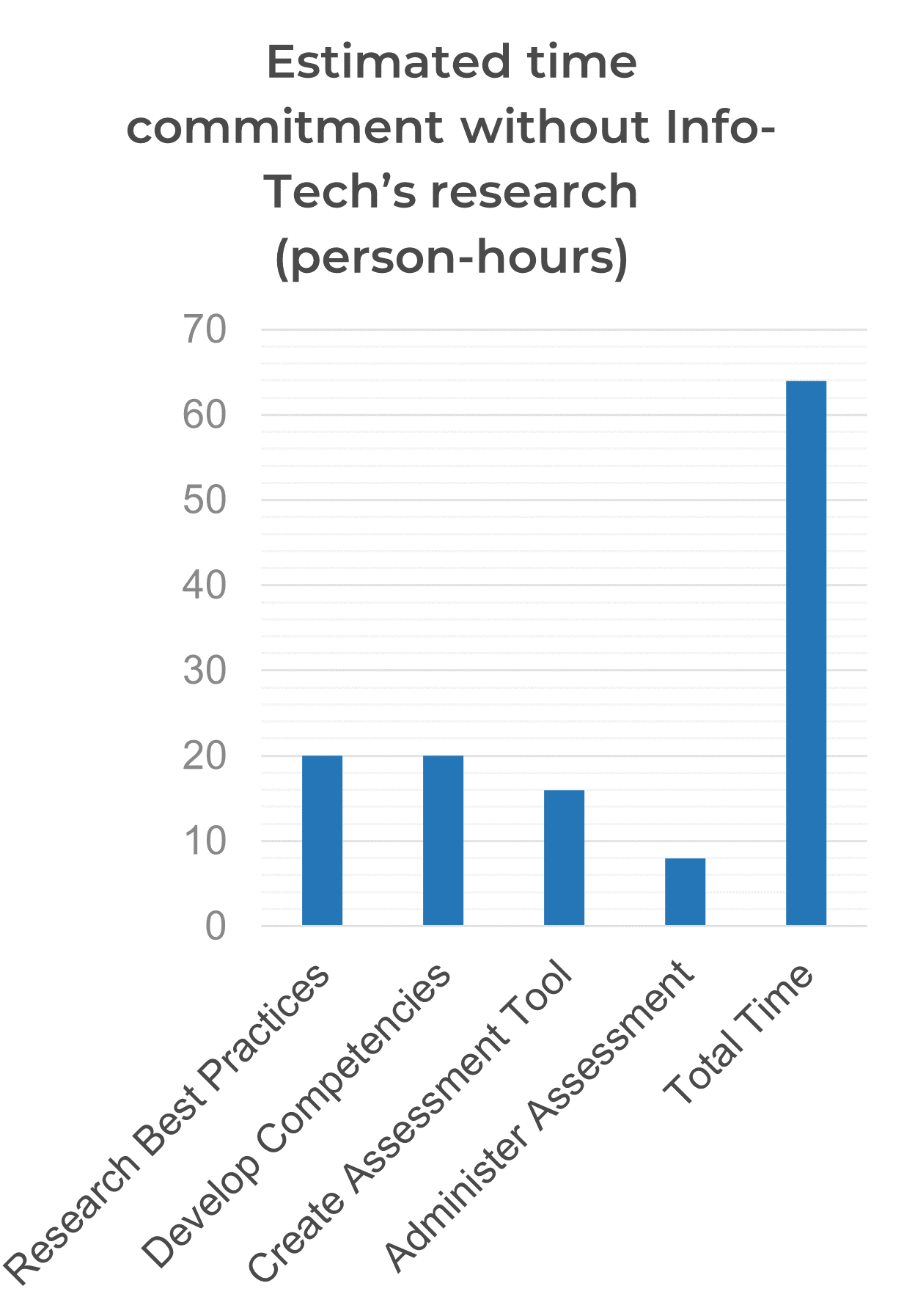

Info-Tech’s method is complemented by a suite of resource management tools and templates

Each phase of this blueprint is accompanied by supporting deliverables to help plan your resource management strategy and sustain your process implementation.

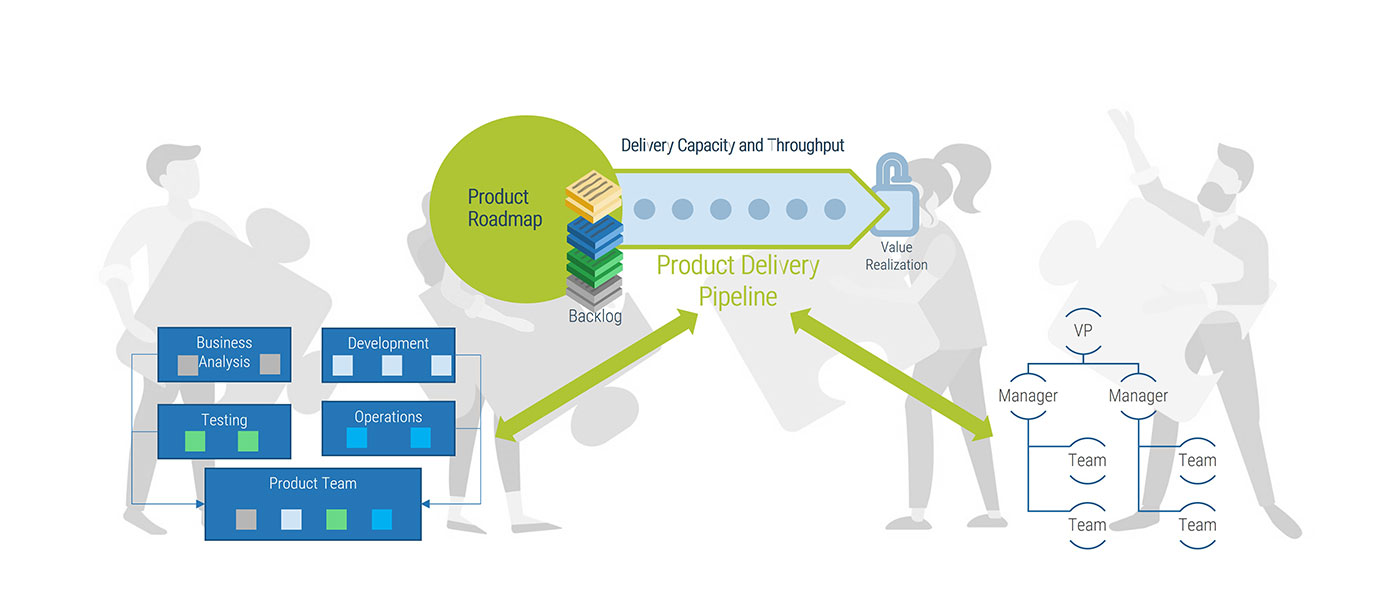

Resource management depends on the flow of information and data from the project level up to functional managers, project managers, and beyond – CIOs, steering committees, and senior executives.

Tools are required to help plan, organize, and facilitate this flow, and each phase of this blueprint is centered around tools and templates to help you successfully support your process implementation.

Take Stock of Organizational Supply and Demand

Tools and Templates:

Design a Realistic Resource Management Process

Tools and Templates:

Implement Sustainable Resource Management Practices

Tools and Templates:

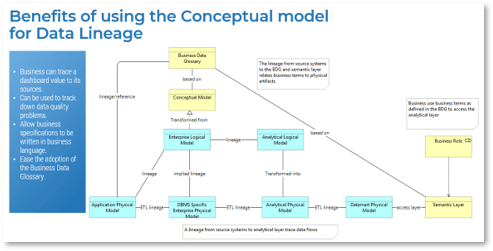

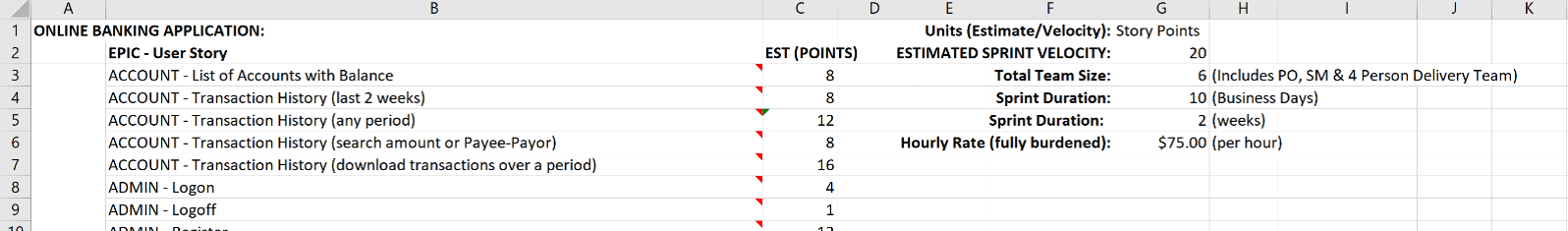

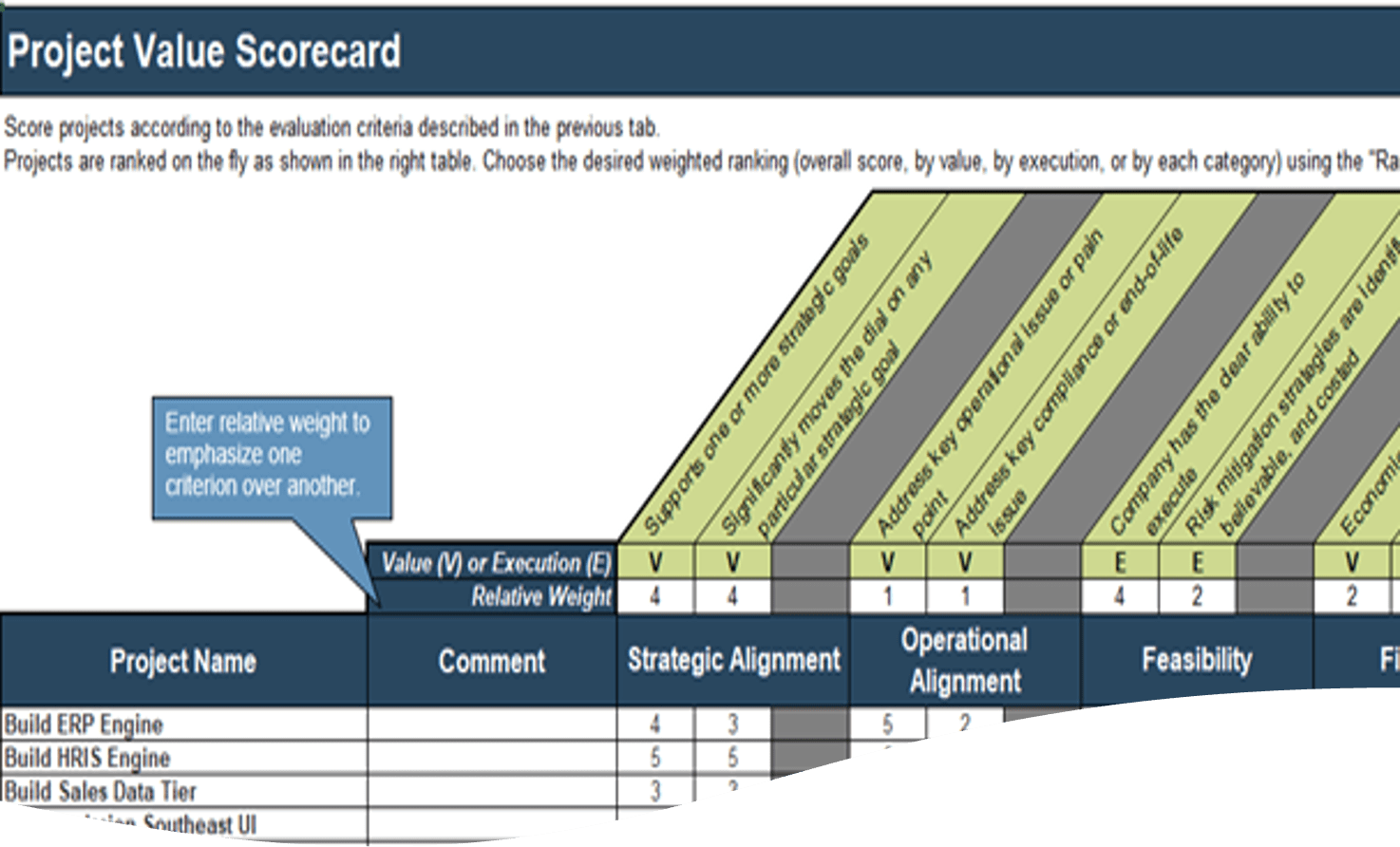

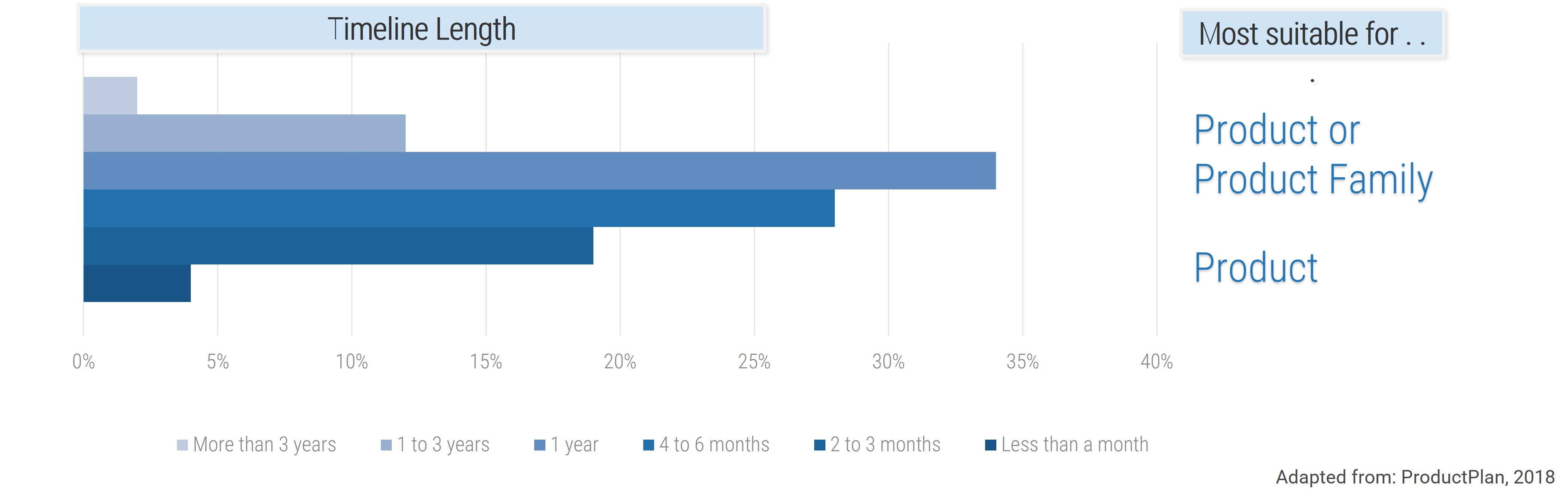

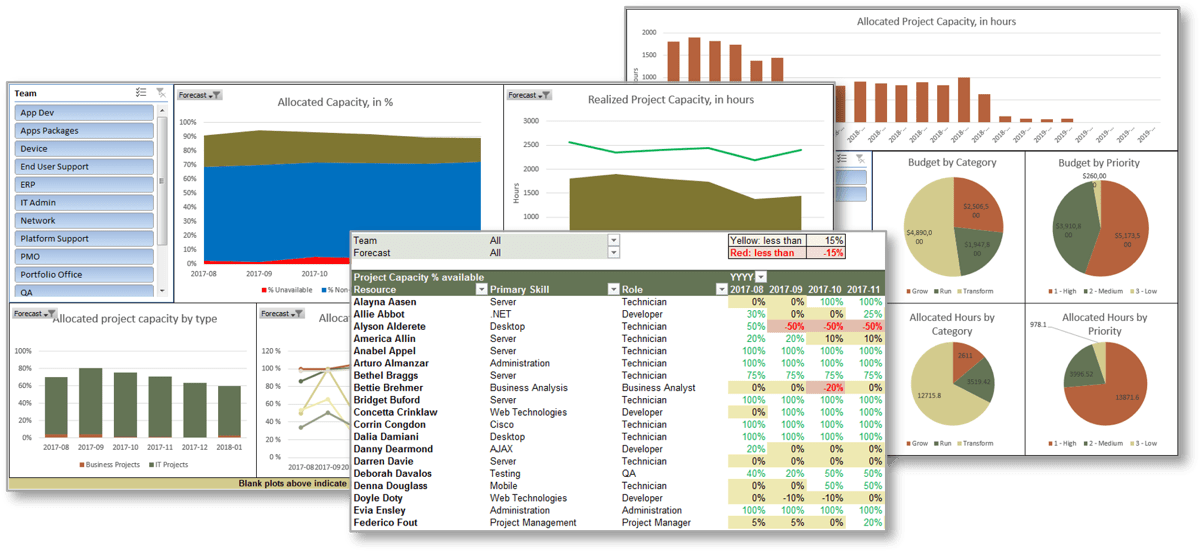

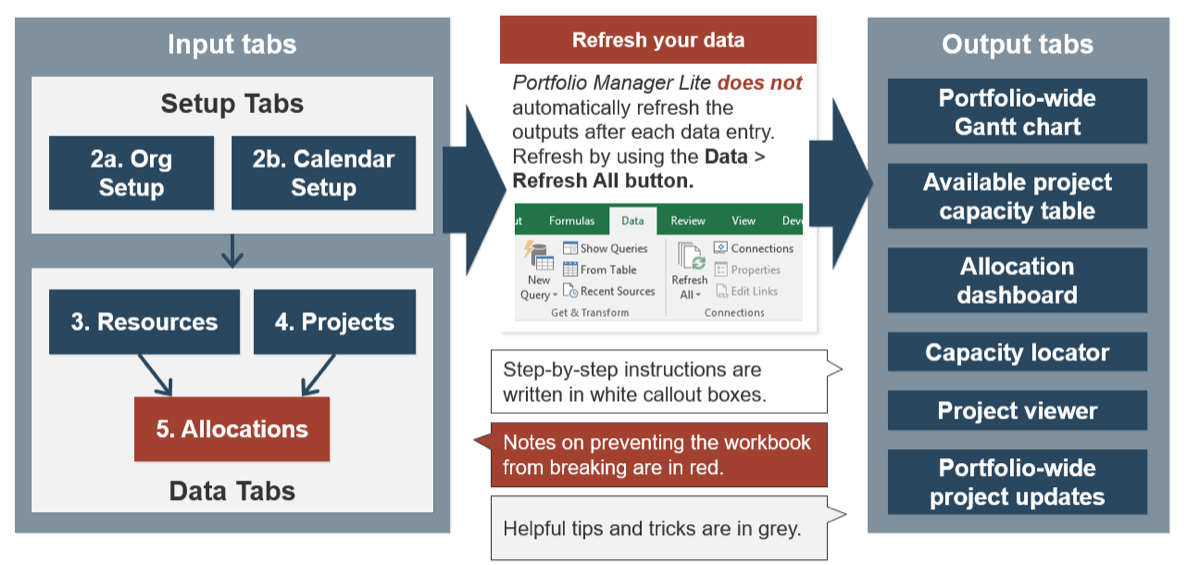

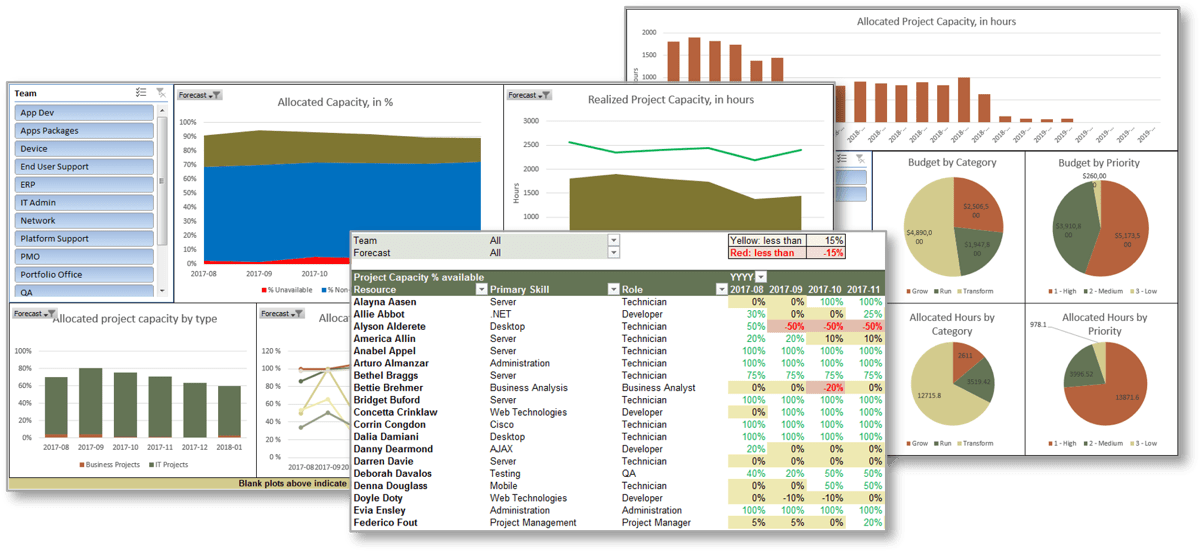

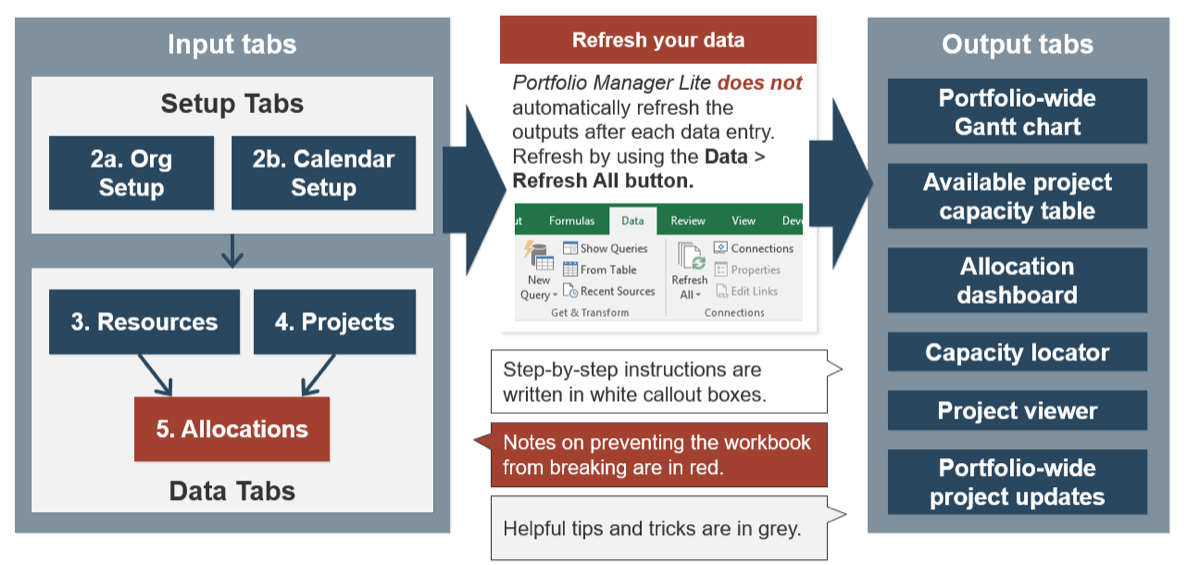

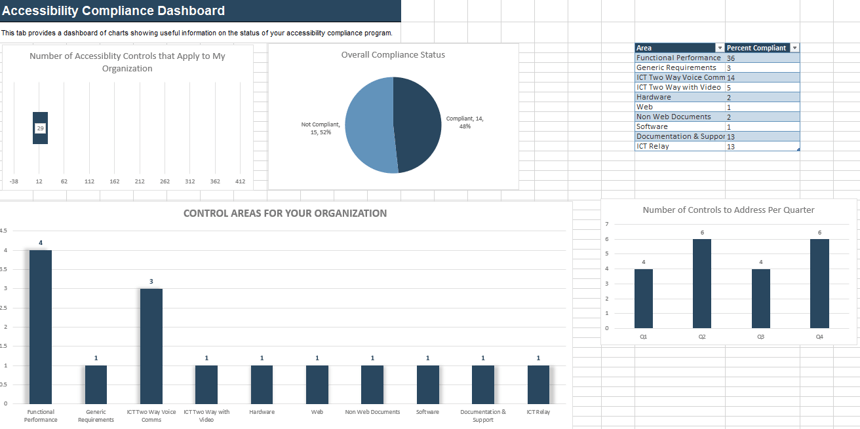

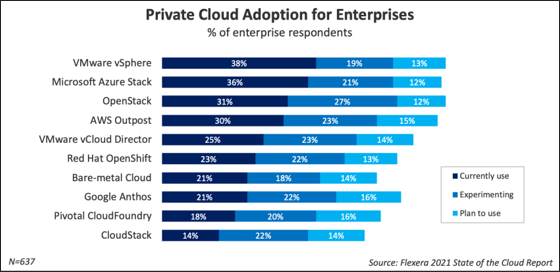

Use Info-Tech’s Portfolio Manager Lite to support your new process without a heavy upfront investment in tools

Spreadsheets can provide a viable alternative for organizations not ready to invest in an expensive tool, or for those not getting what they need from their commercial selections.

While homegrown solutions like spreadsheets and intranet sites lack the robust functionality of commercial offerings, they have dramatically lower complexity and cost-in-use.

Info-Tech’s Portfolio Manager Lite is a sophisticated, scalable, and highly customizable spreadsheet-based solution that will get your new resource management process up and running, without a heavy upfront cost.

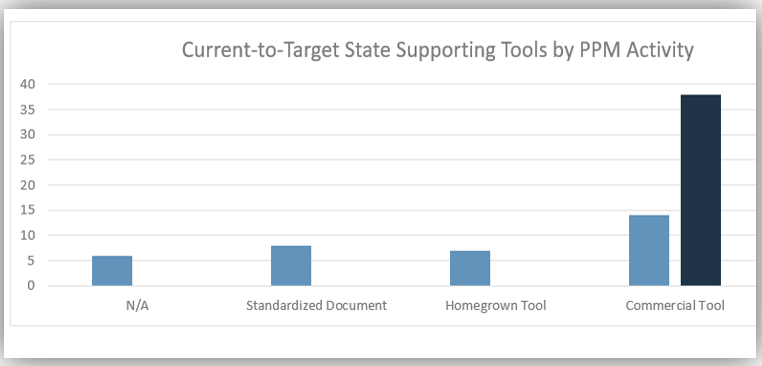

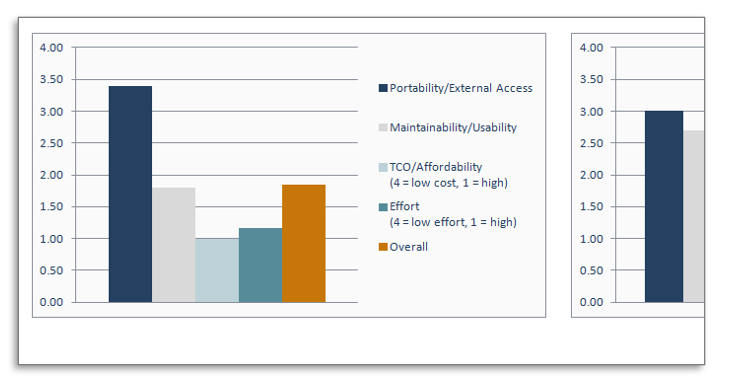

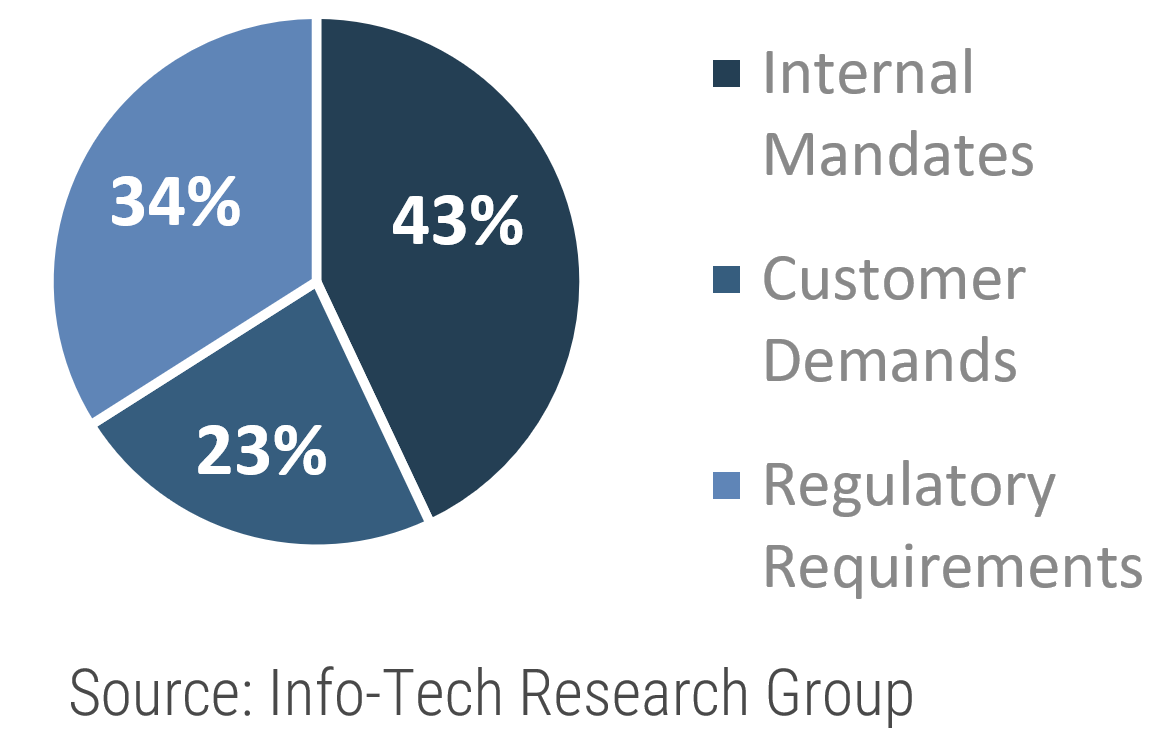

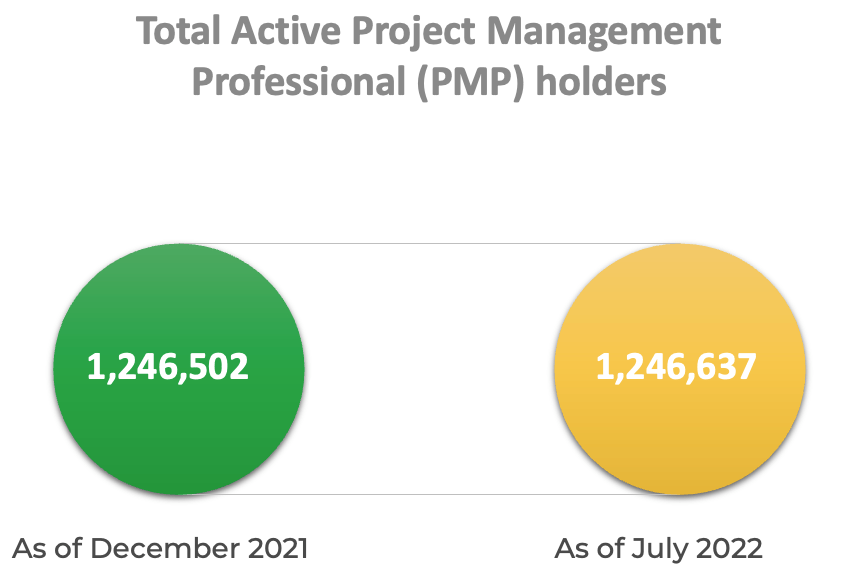

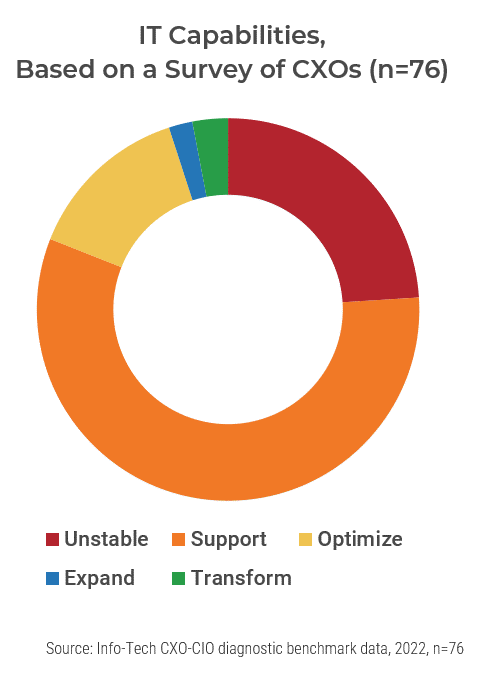

Kinds of PPM solutions used by Info-Tech clients

Homemade – 46%

Commercial – 33%

No Solution – 21%

(Info-Tech Research Group (2016), N=433)

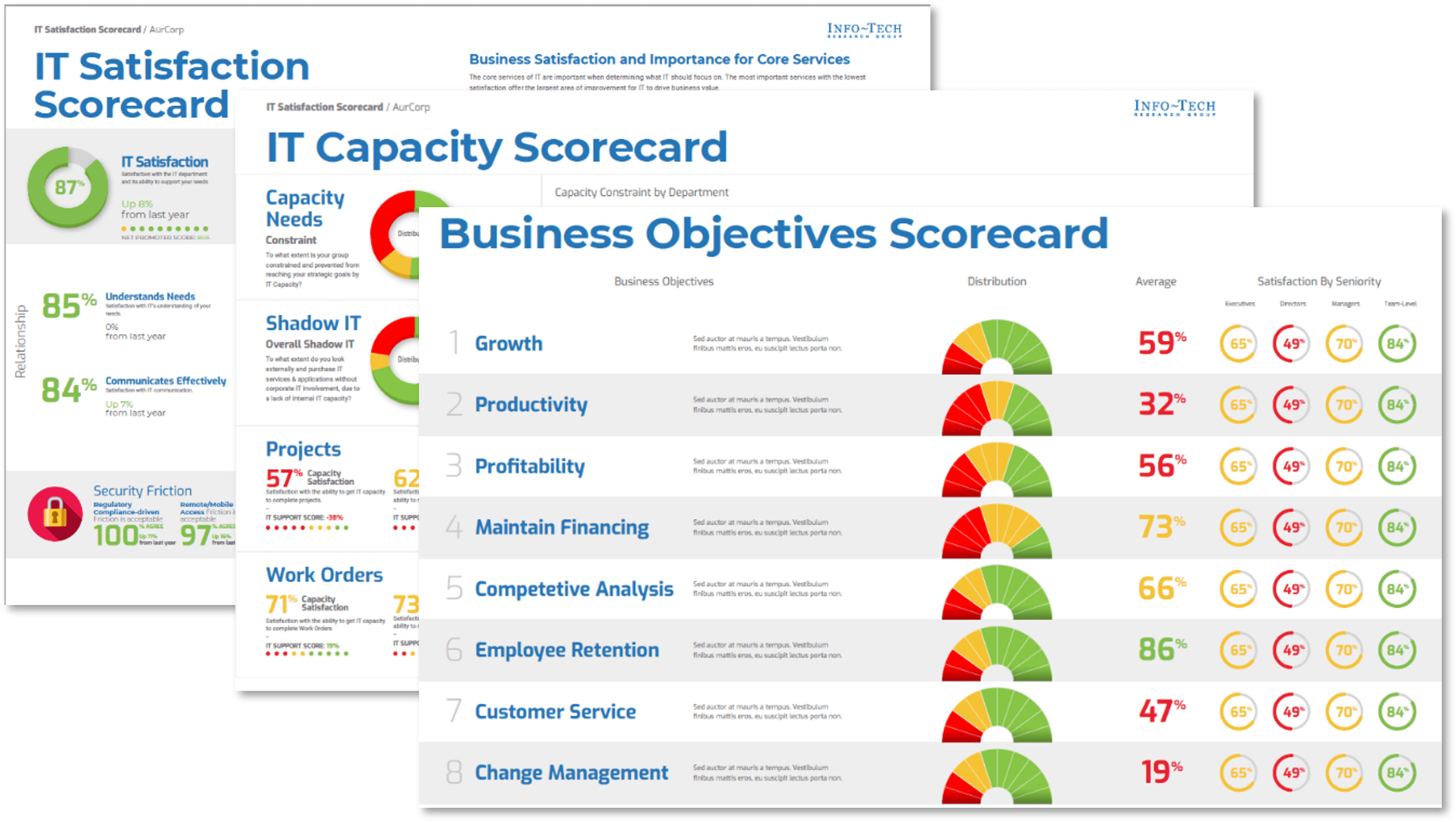

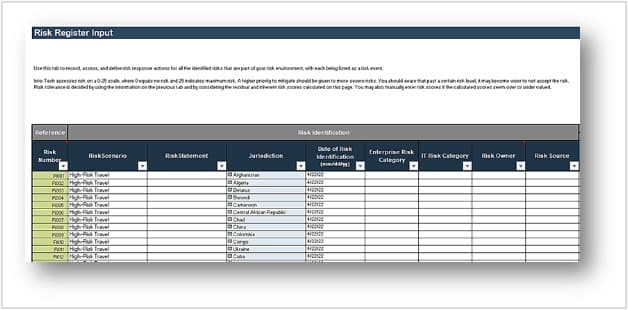

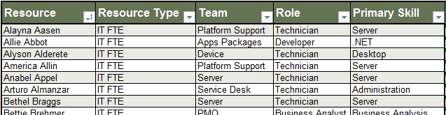

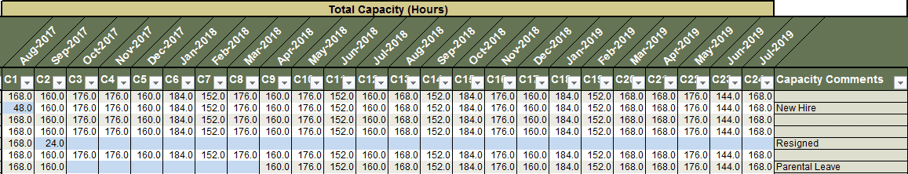

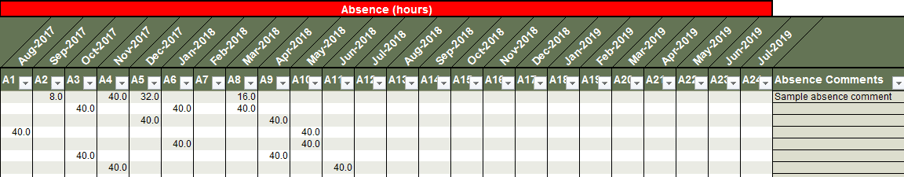

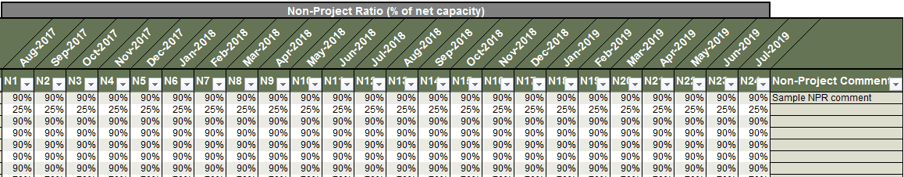

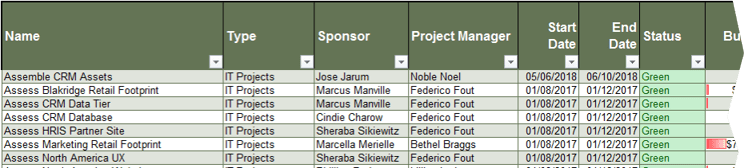

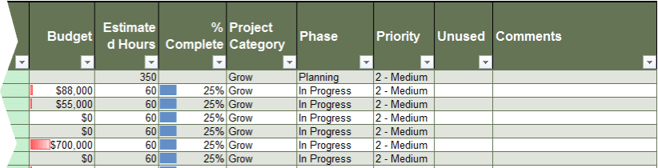

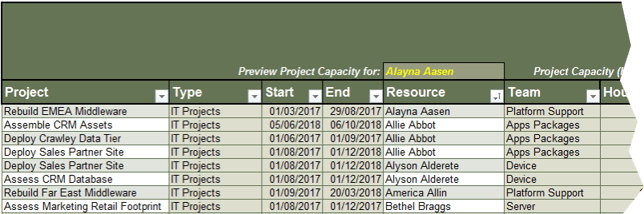

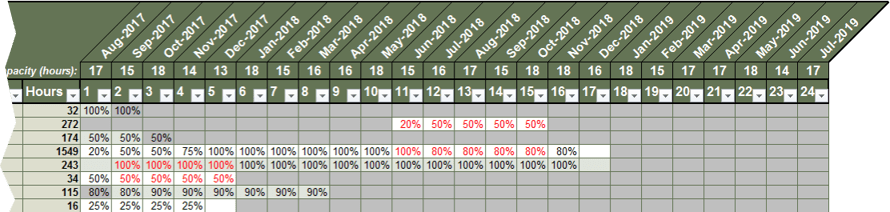

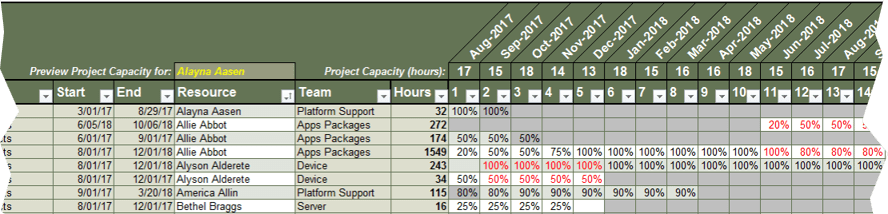

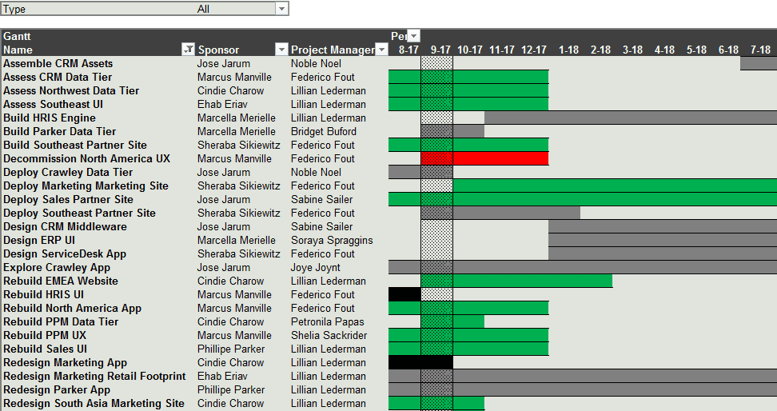

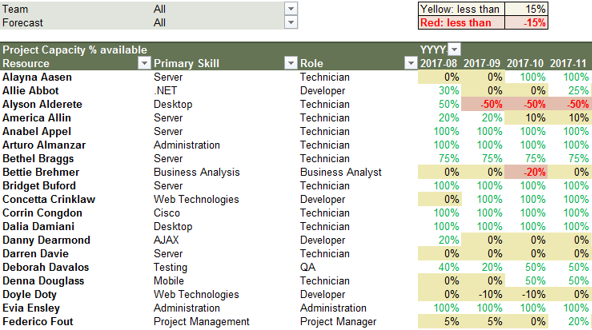

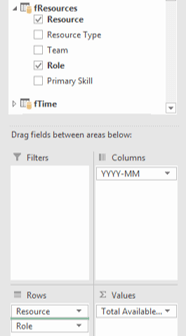

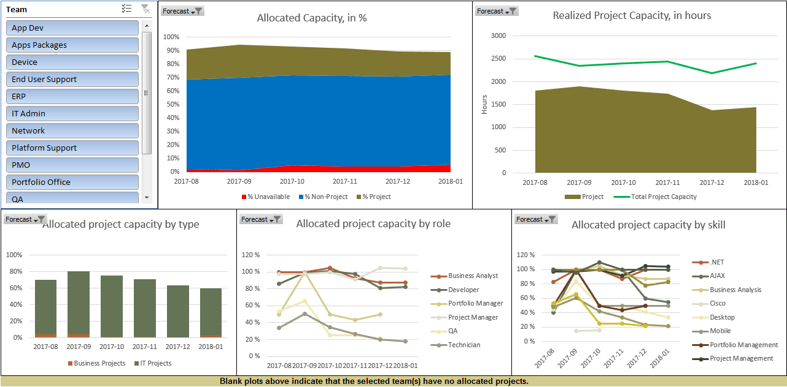

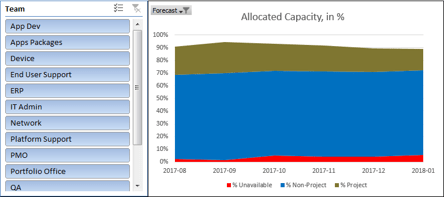

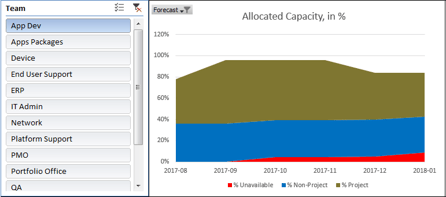

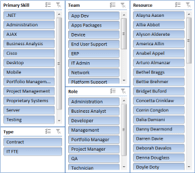

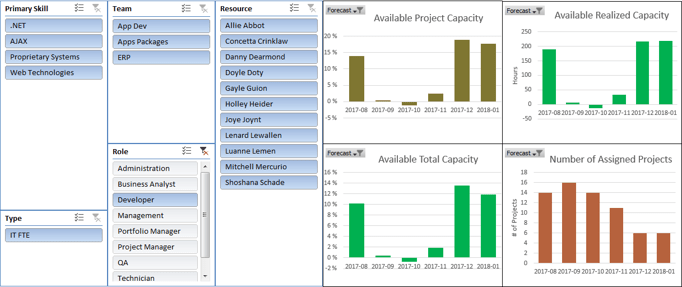

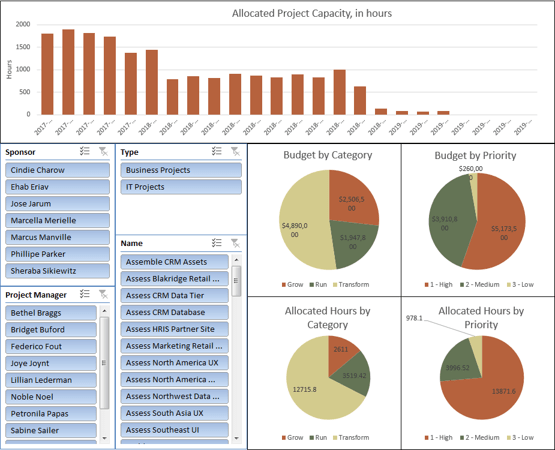

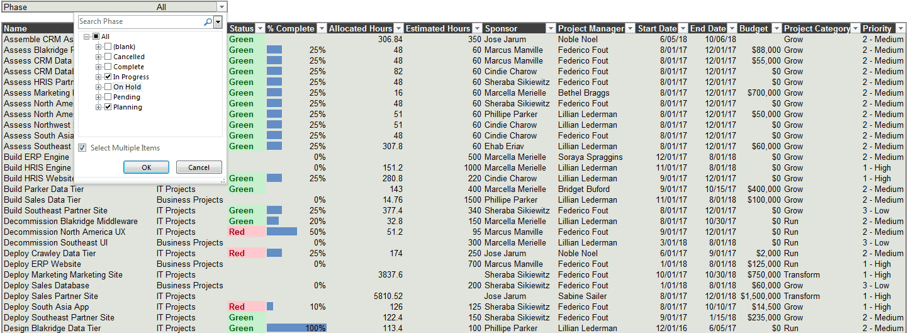

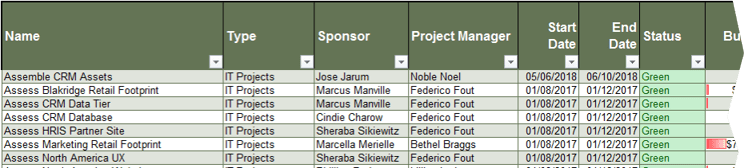

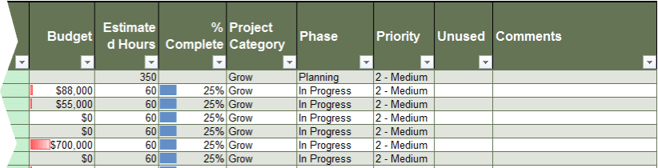

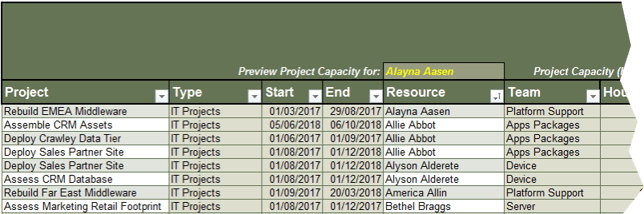

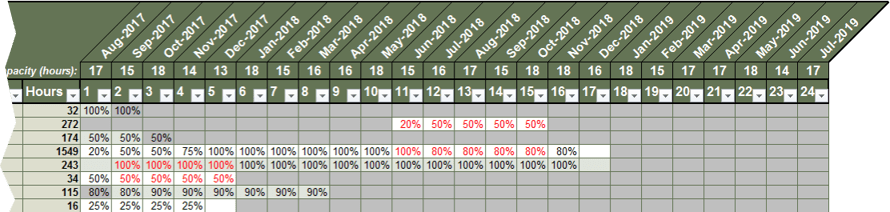

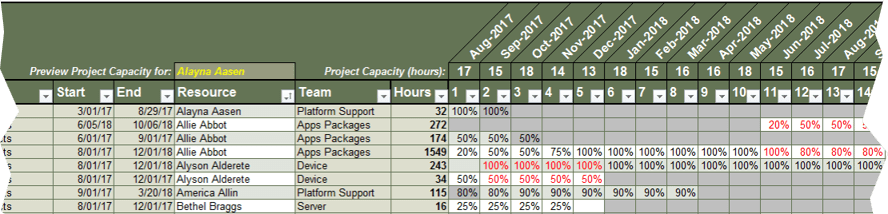

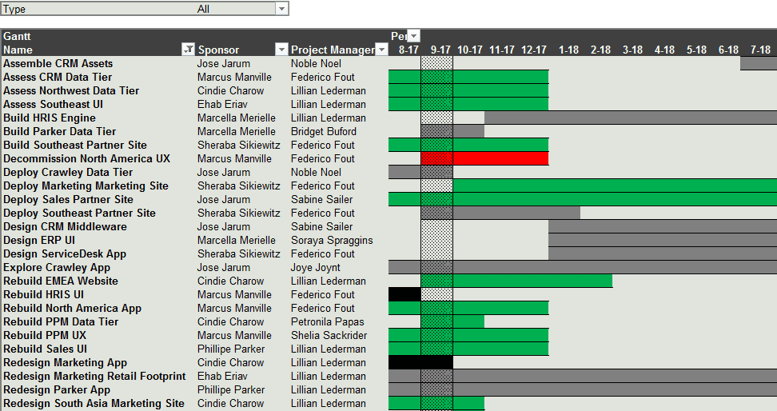

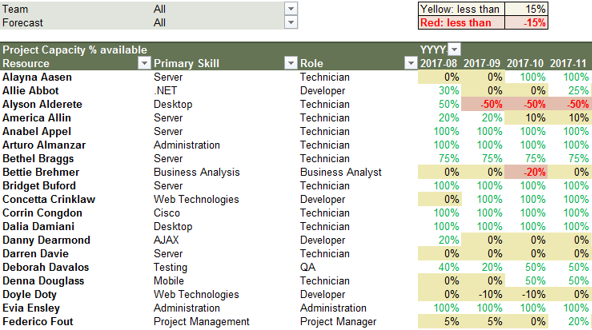

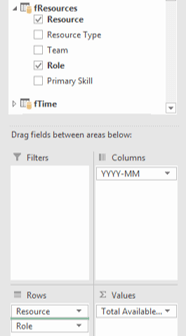

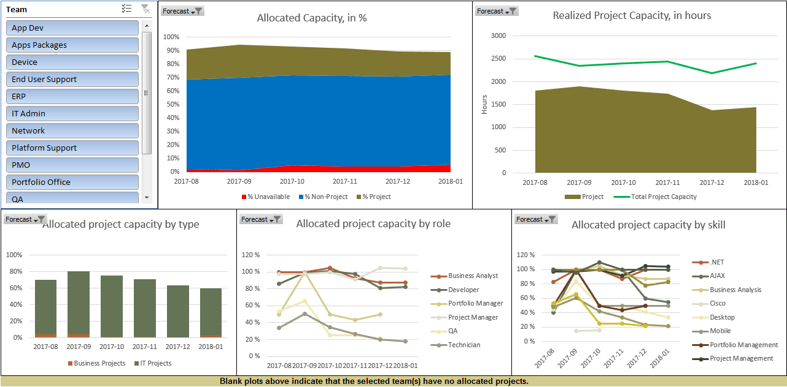

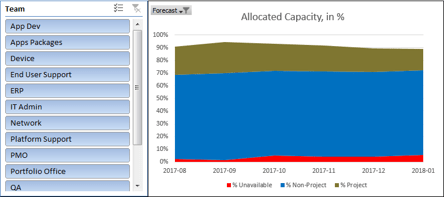

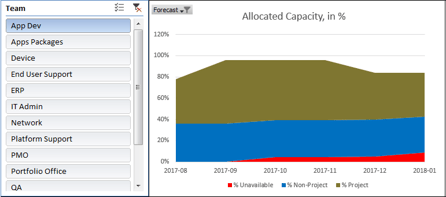

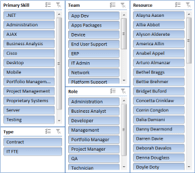

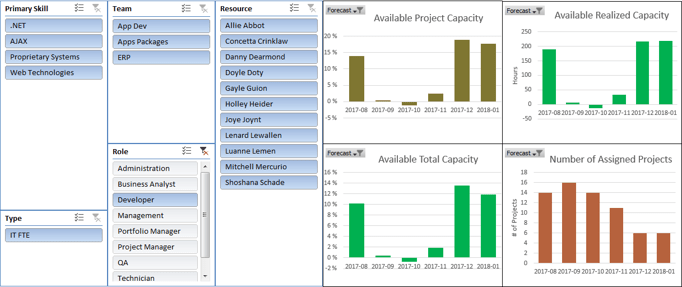

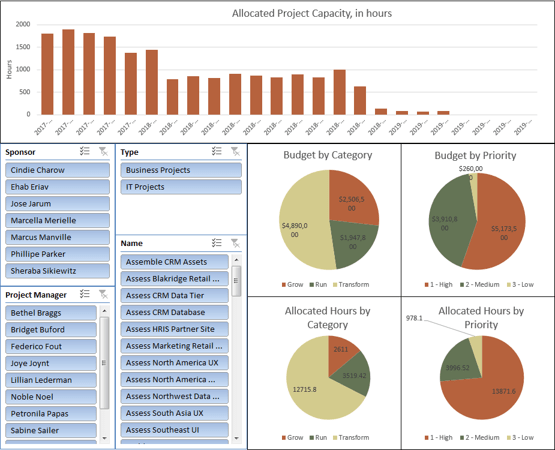

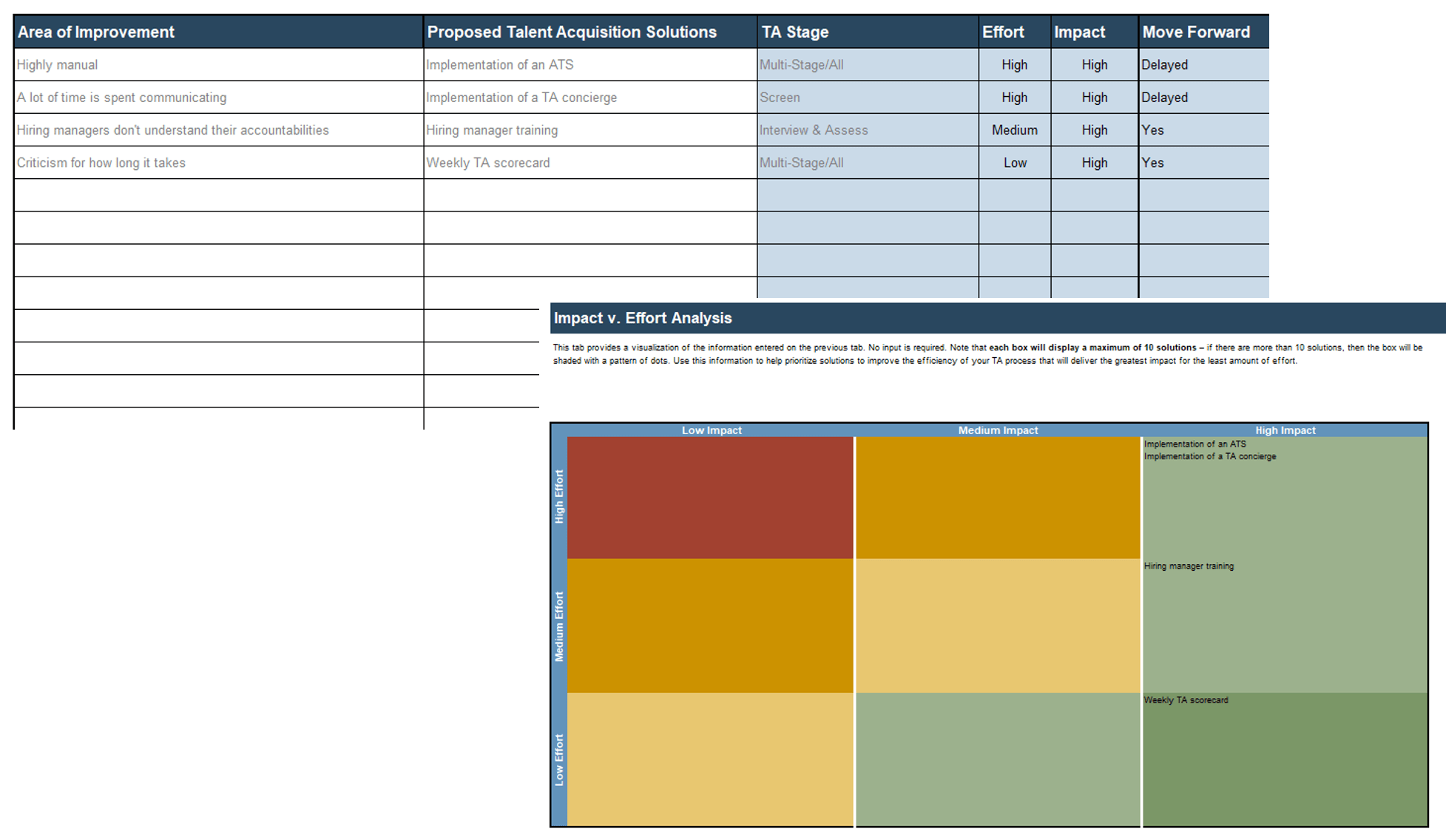

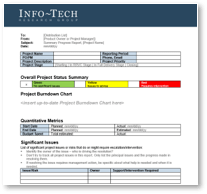

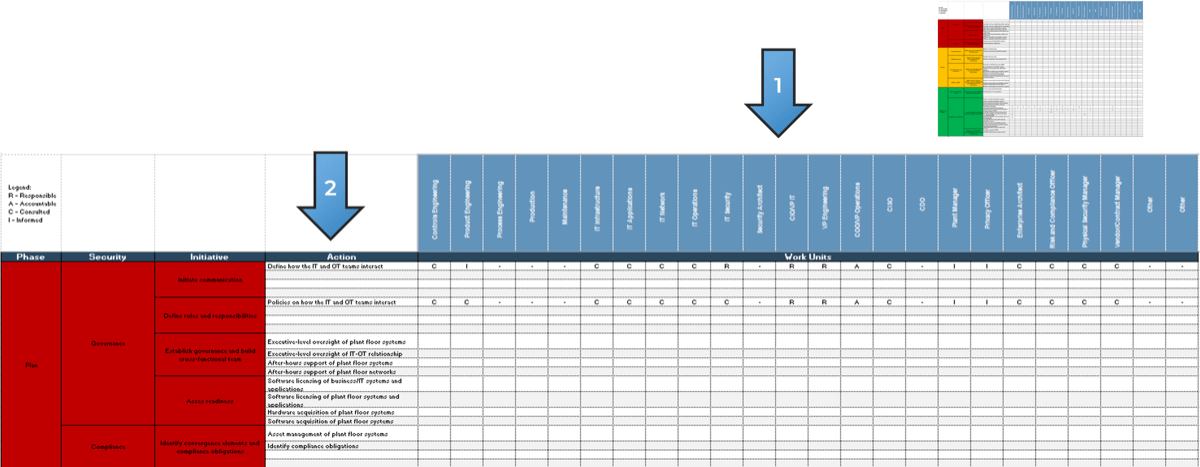

Samples of Portfolio Manager Lite's output and reporting tabs

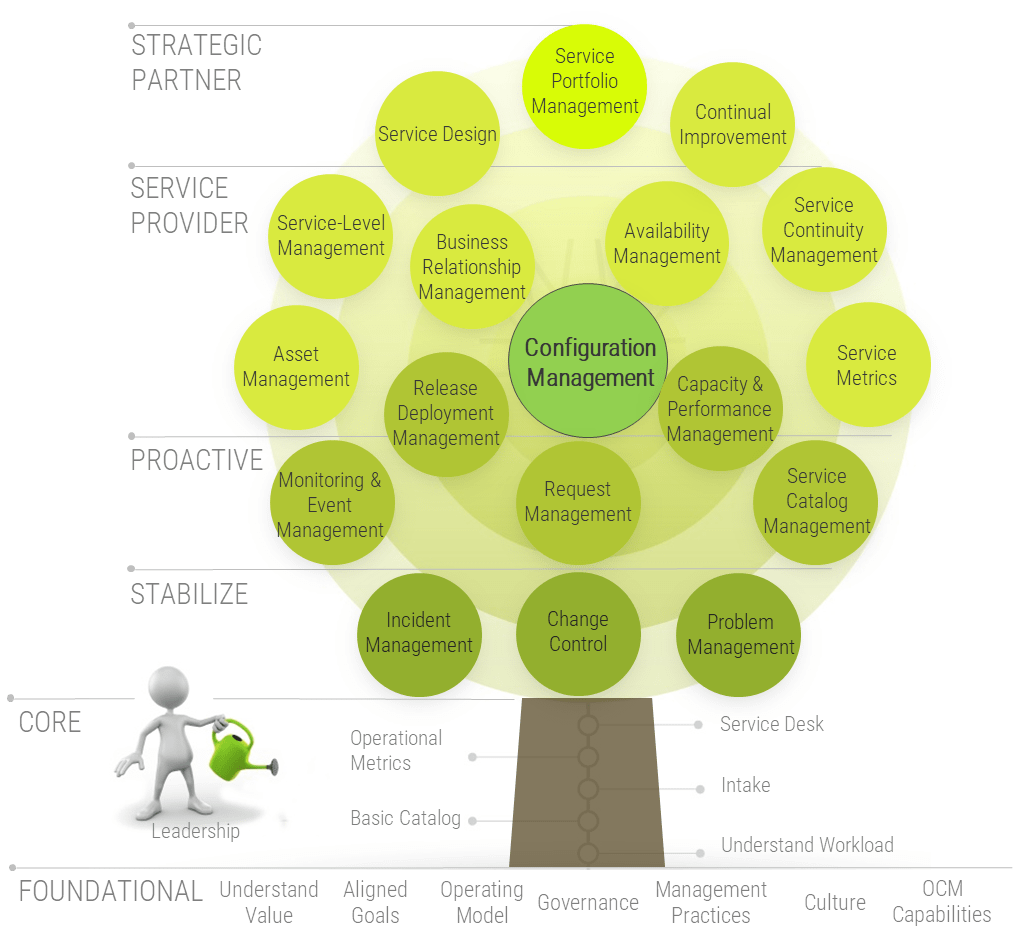

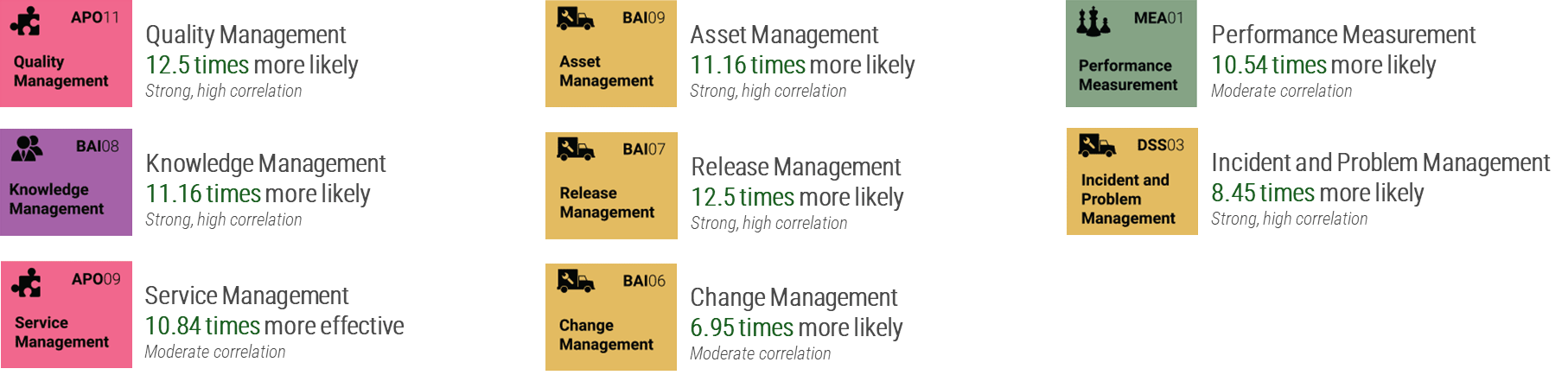

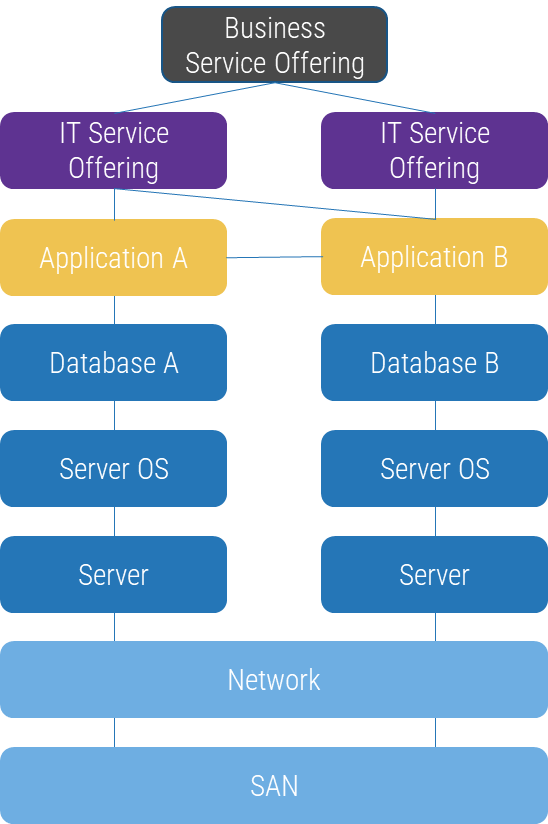

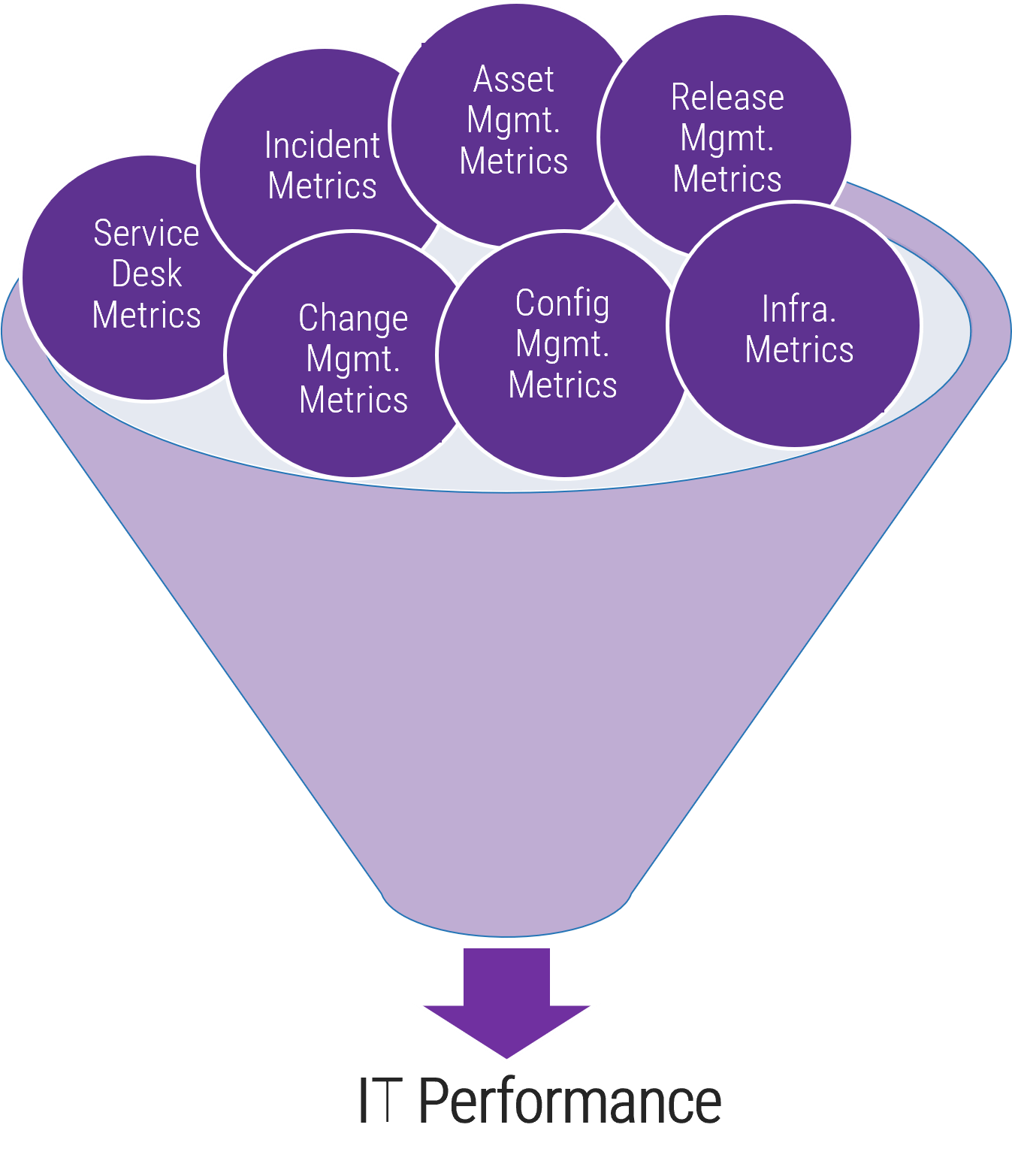

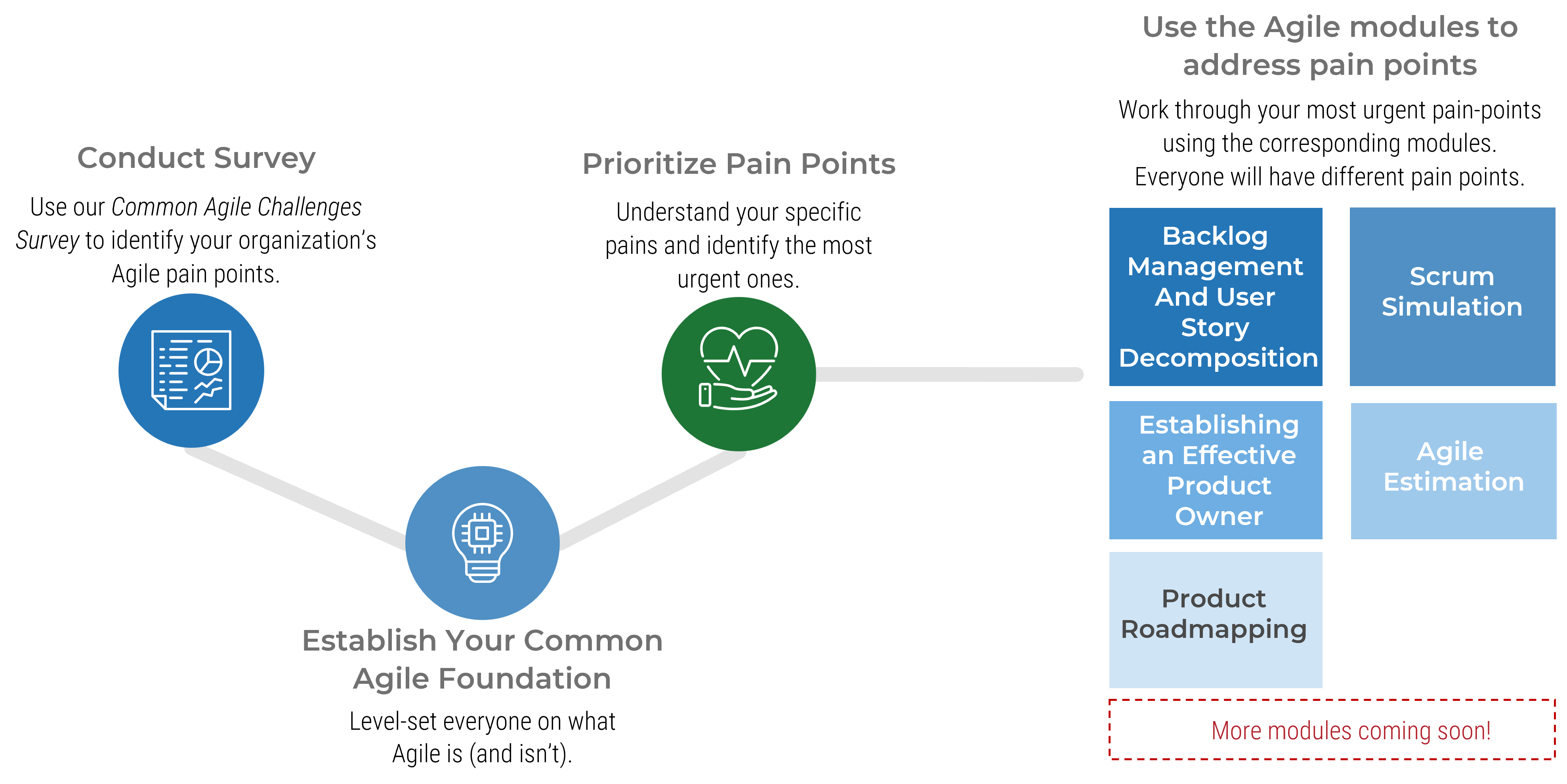

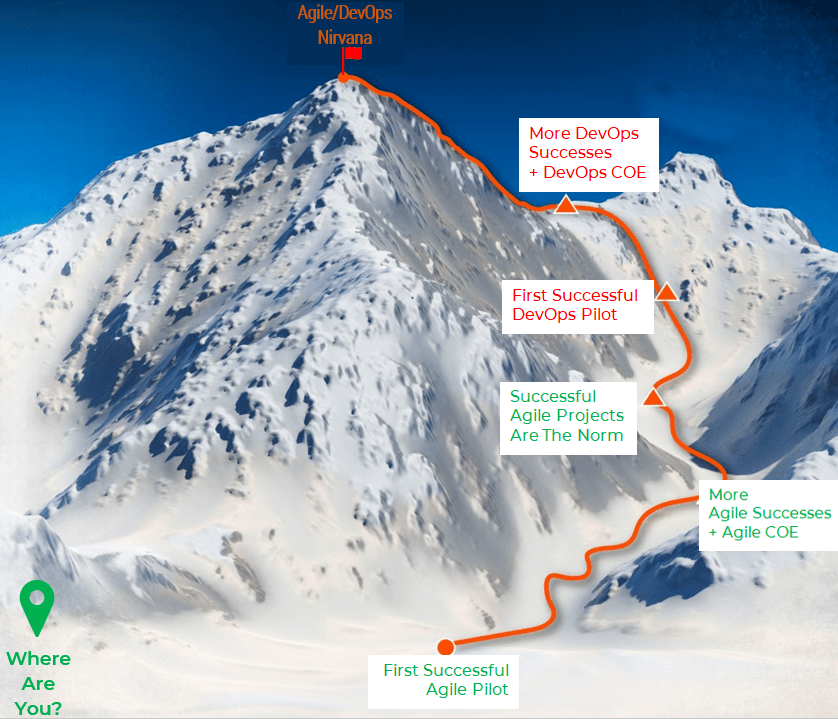

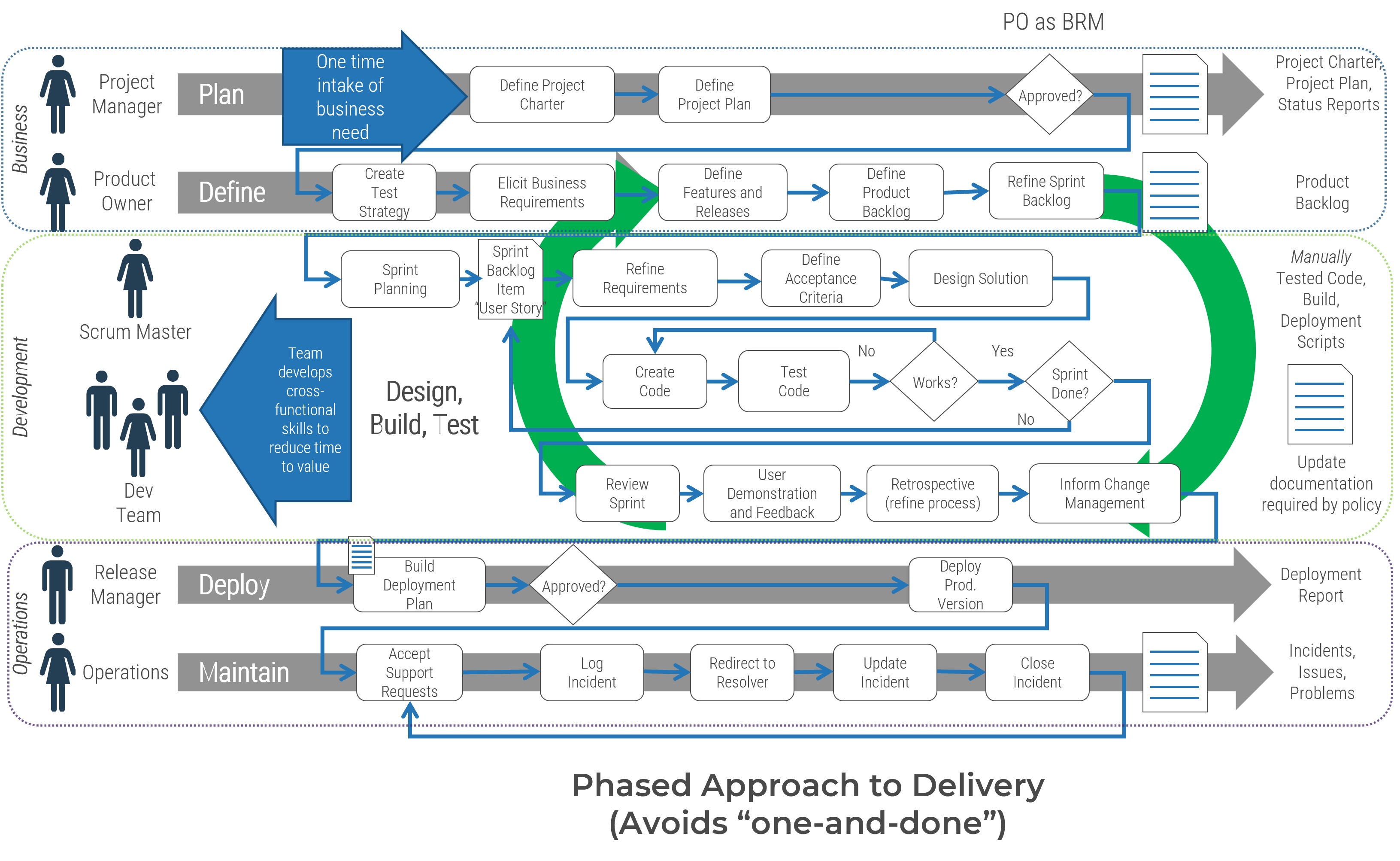

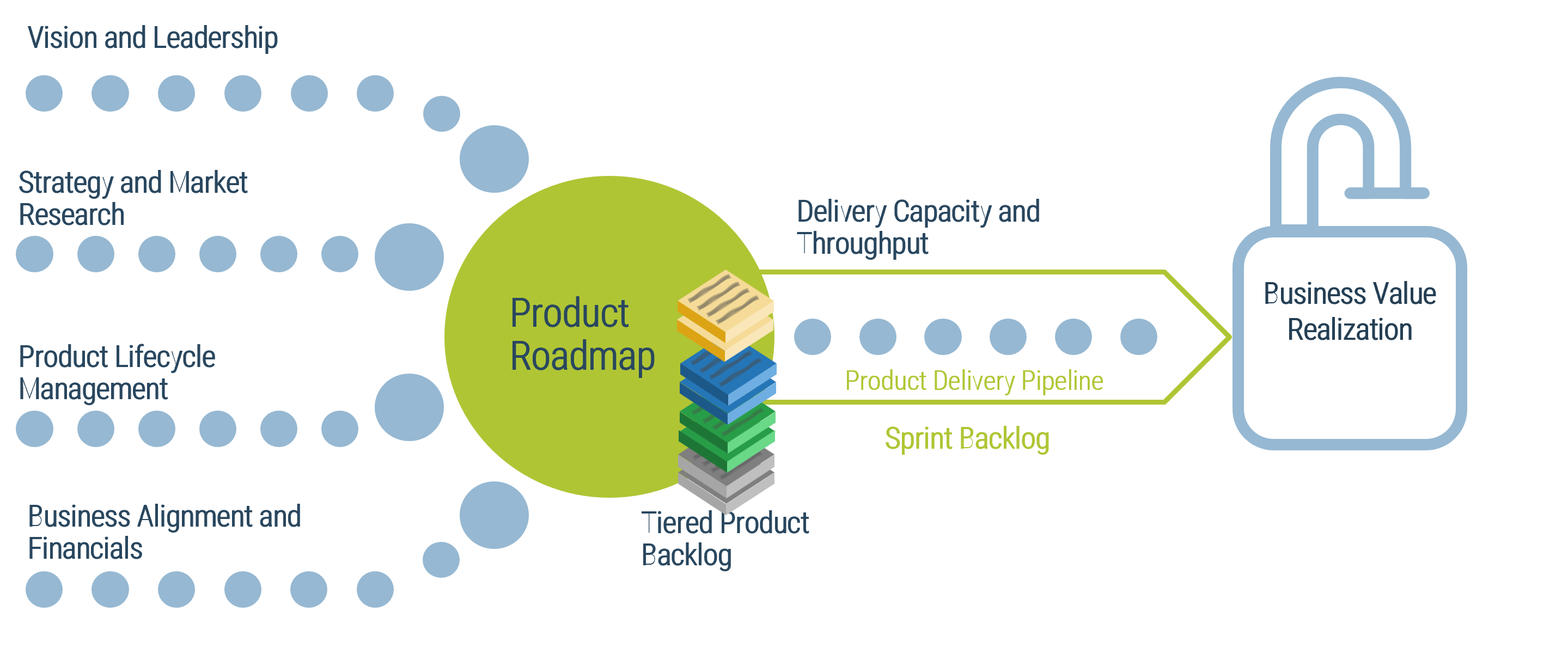

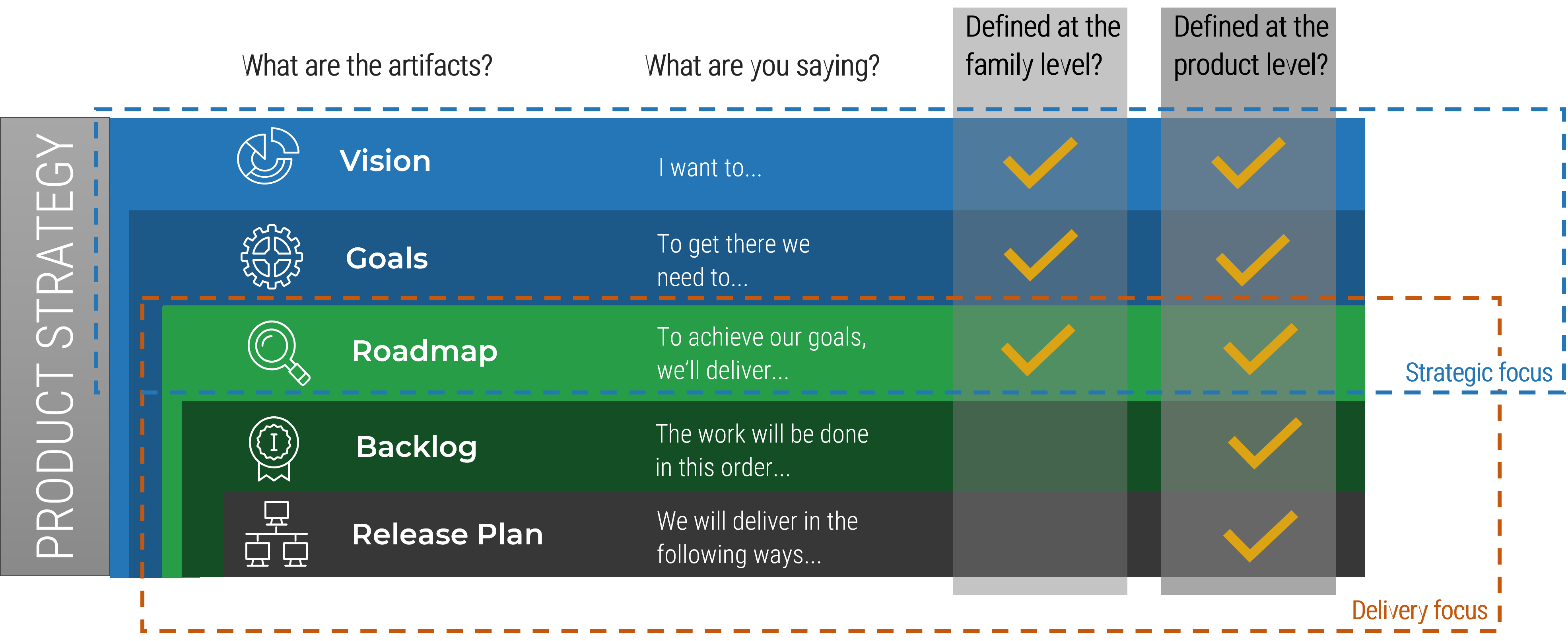

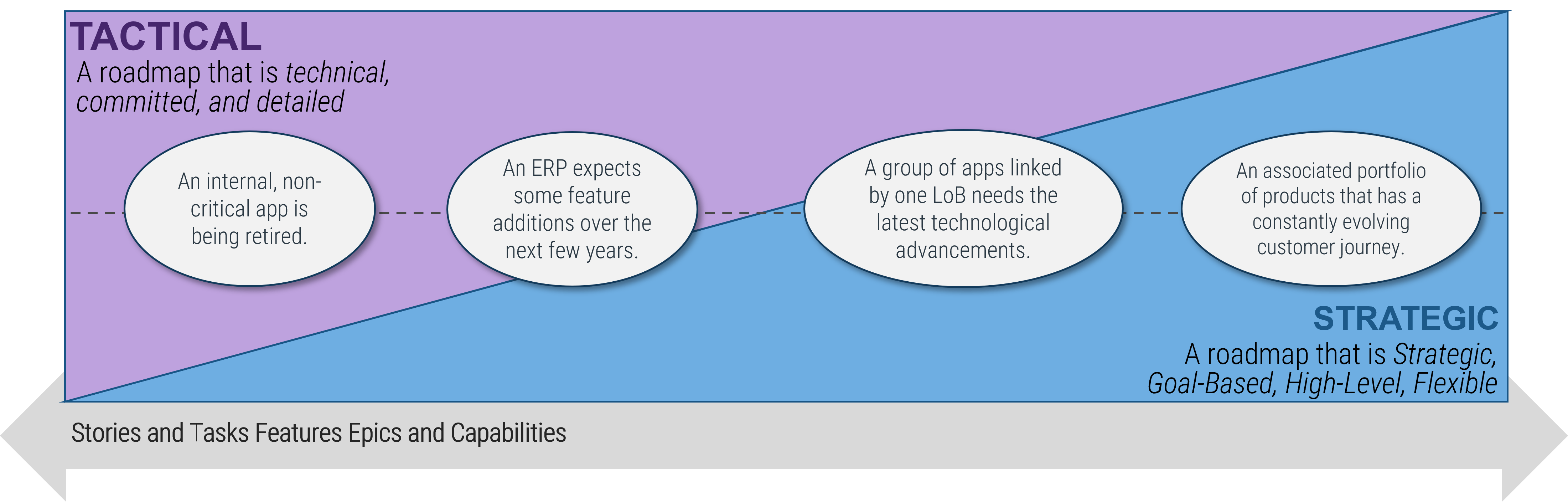

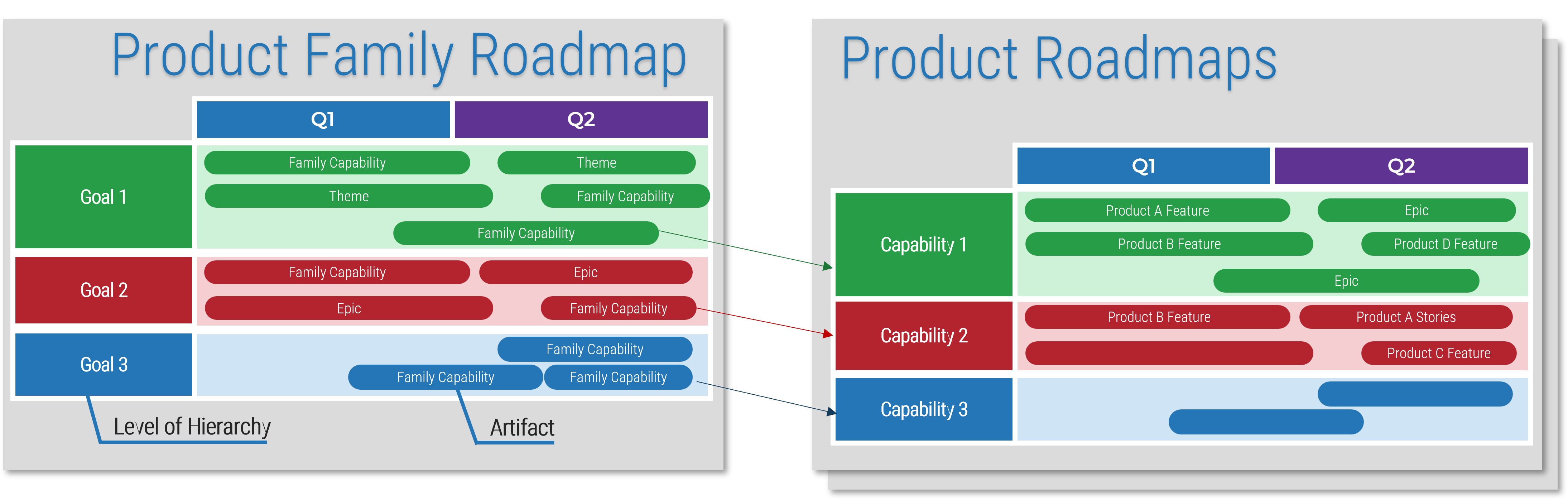

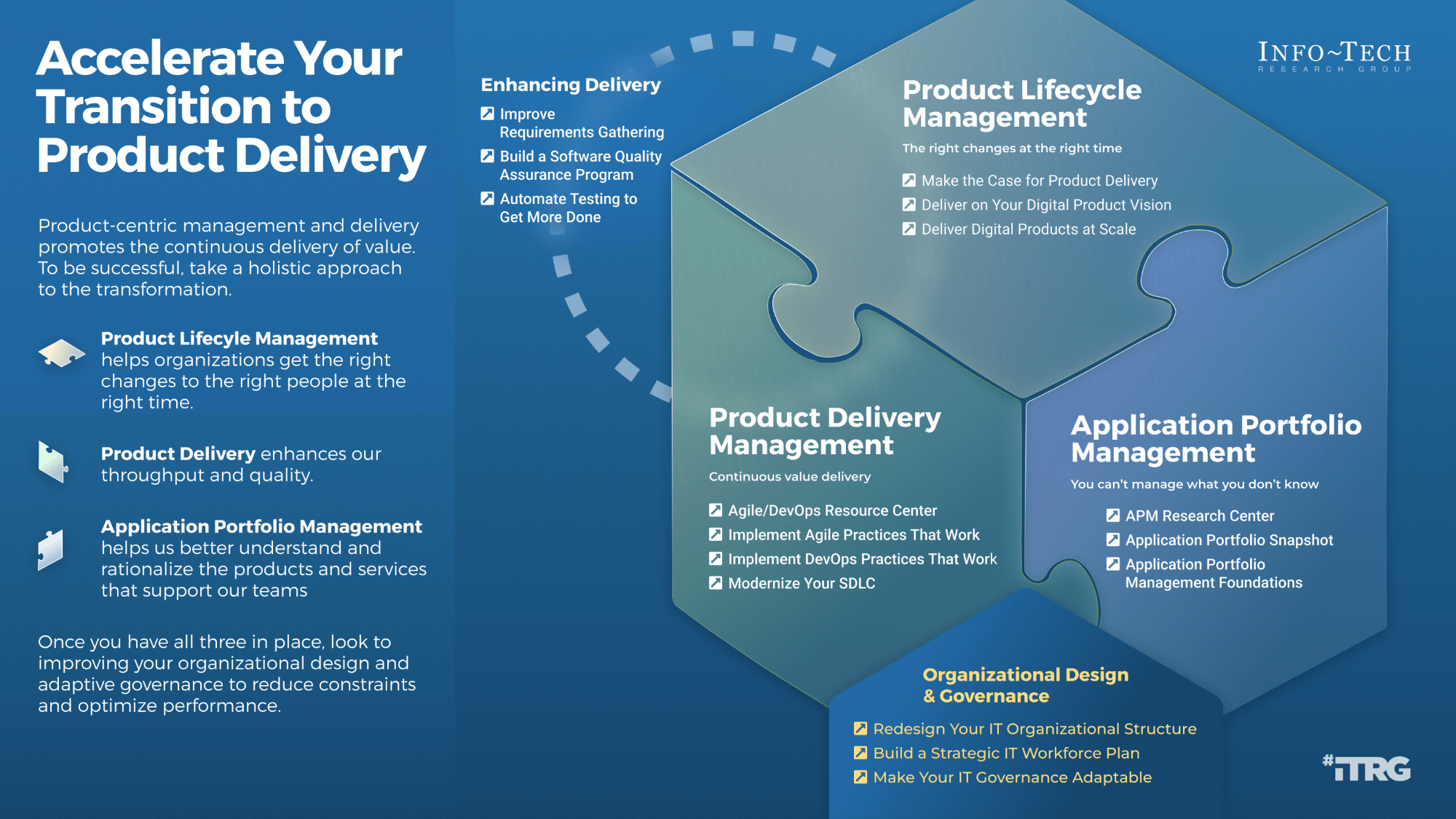

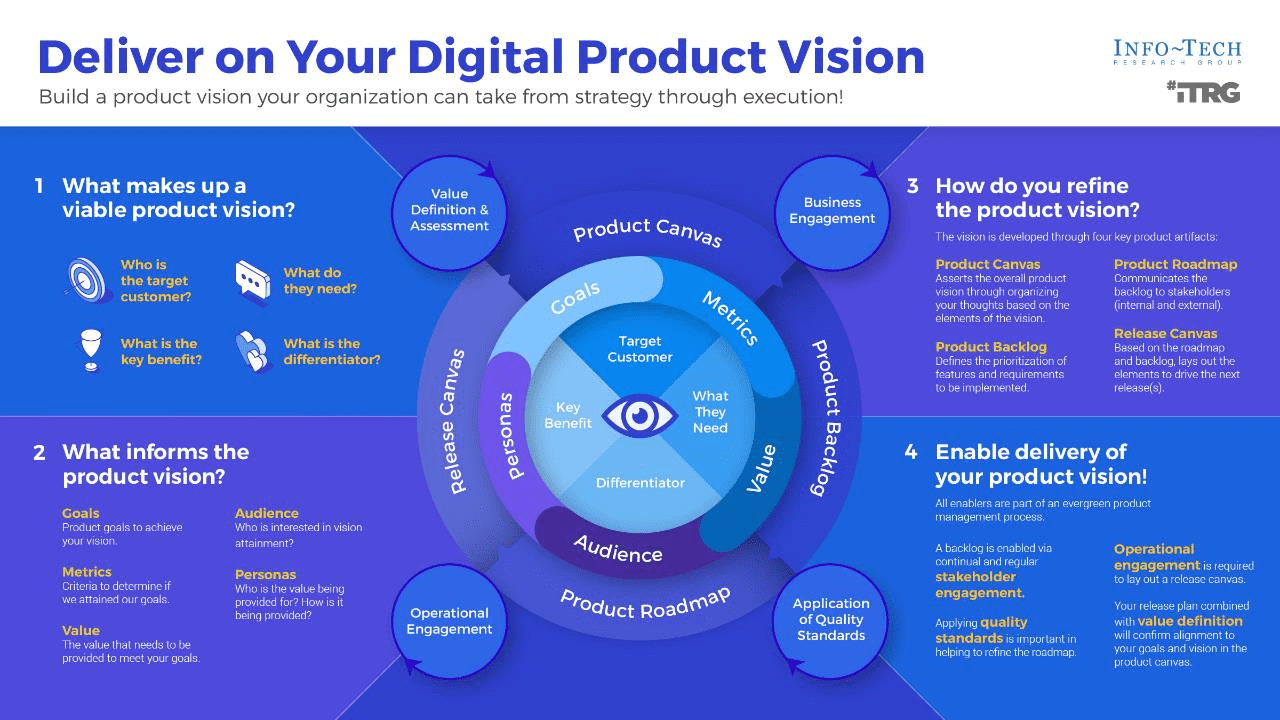

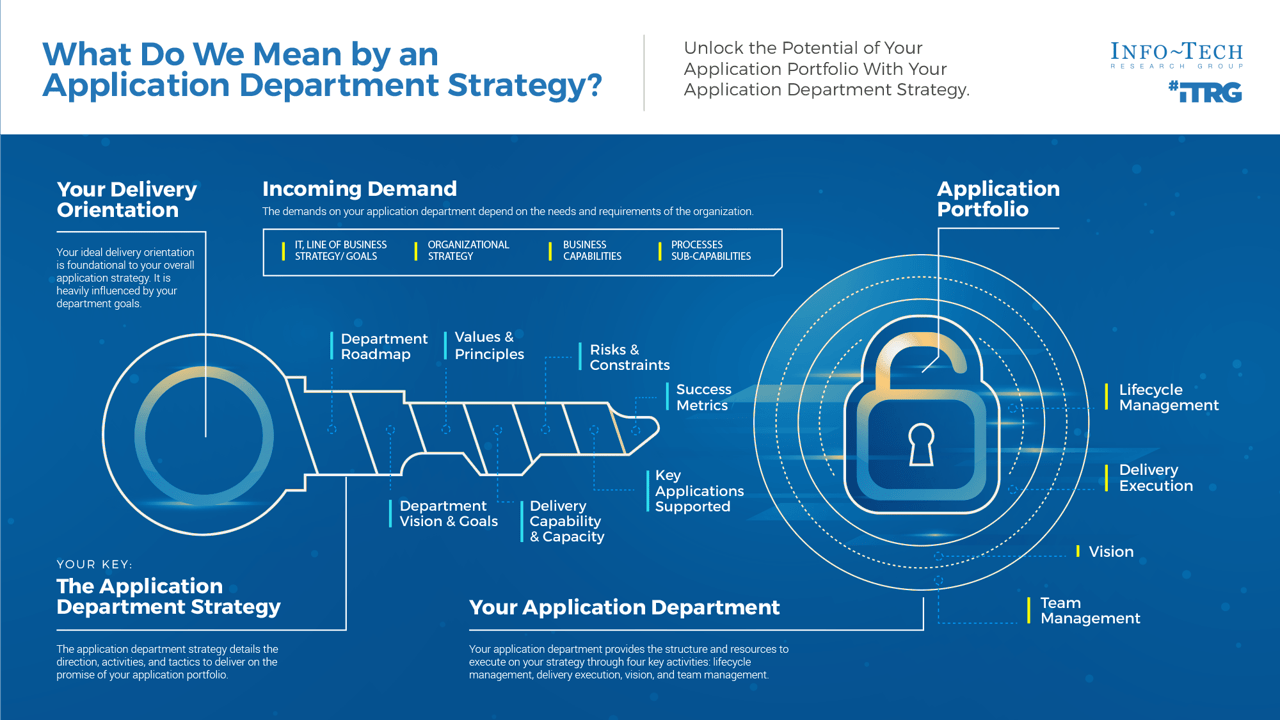

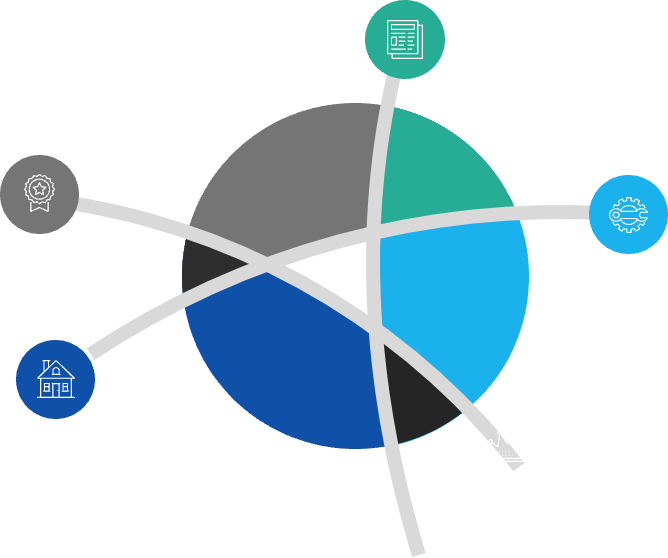

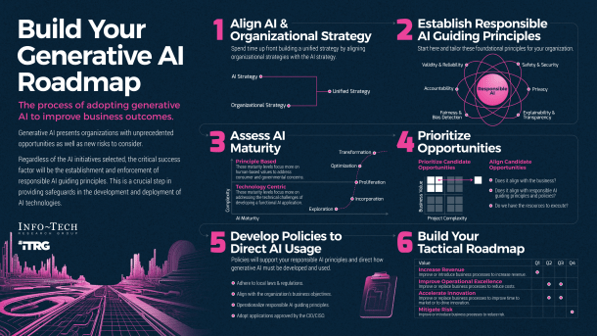

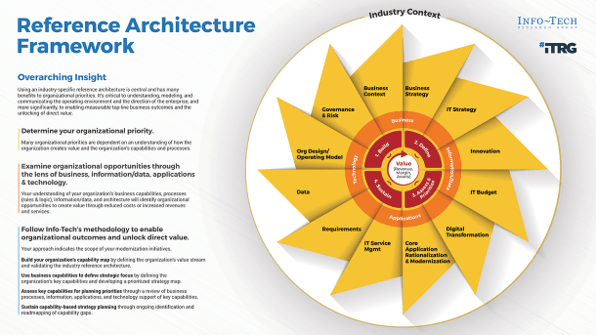

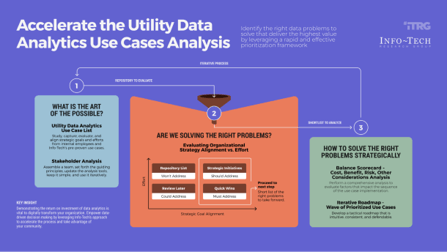

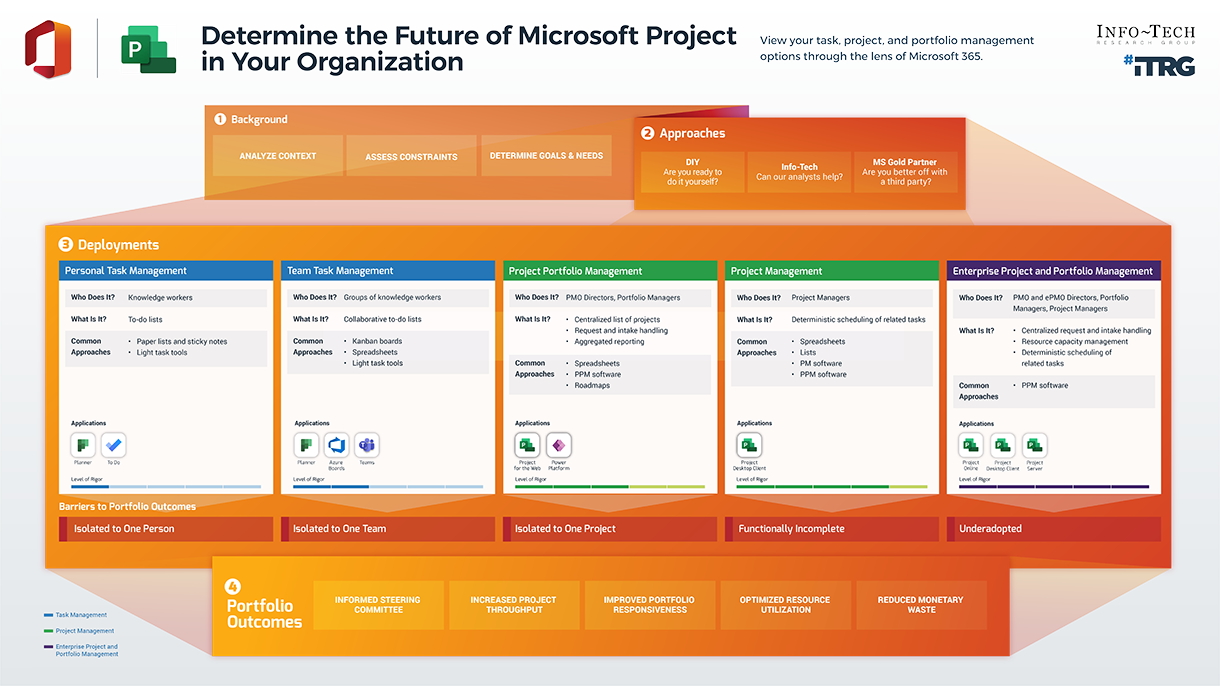

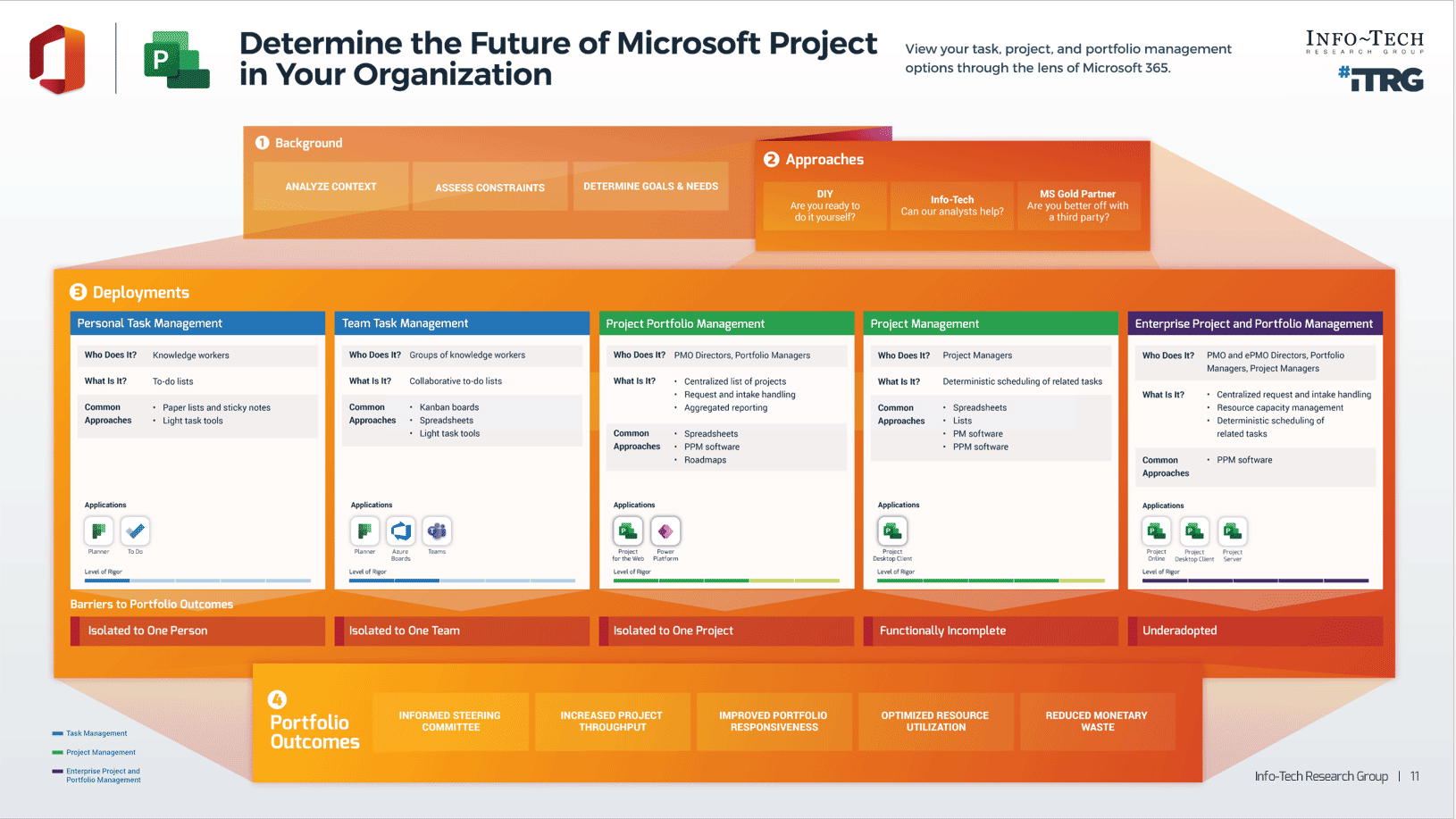

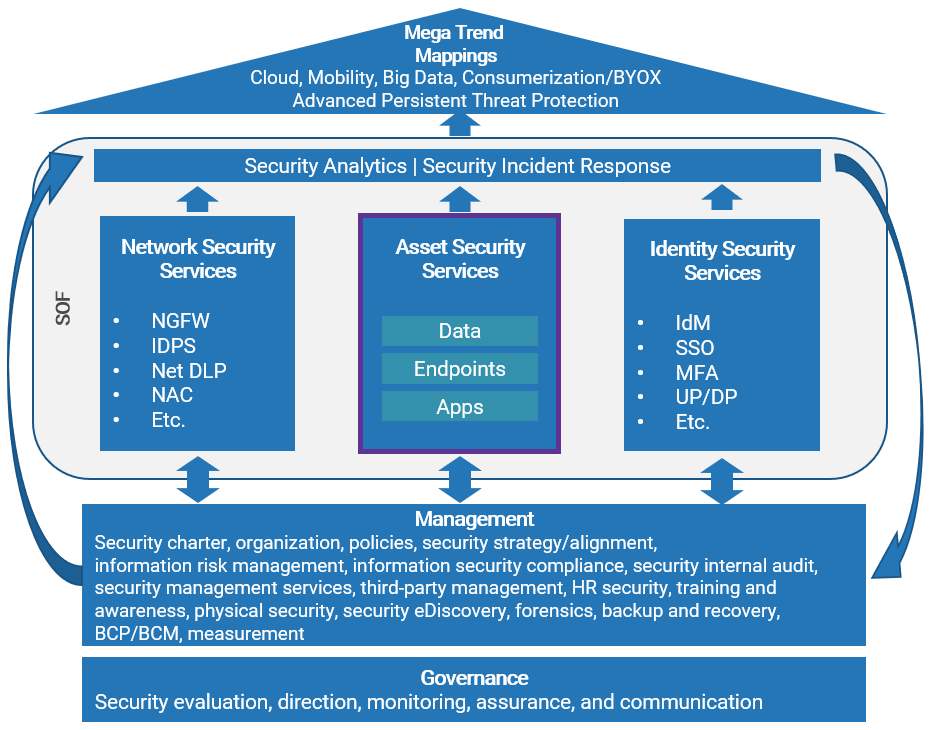

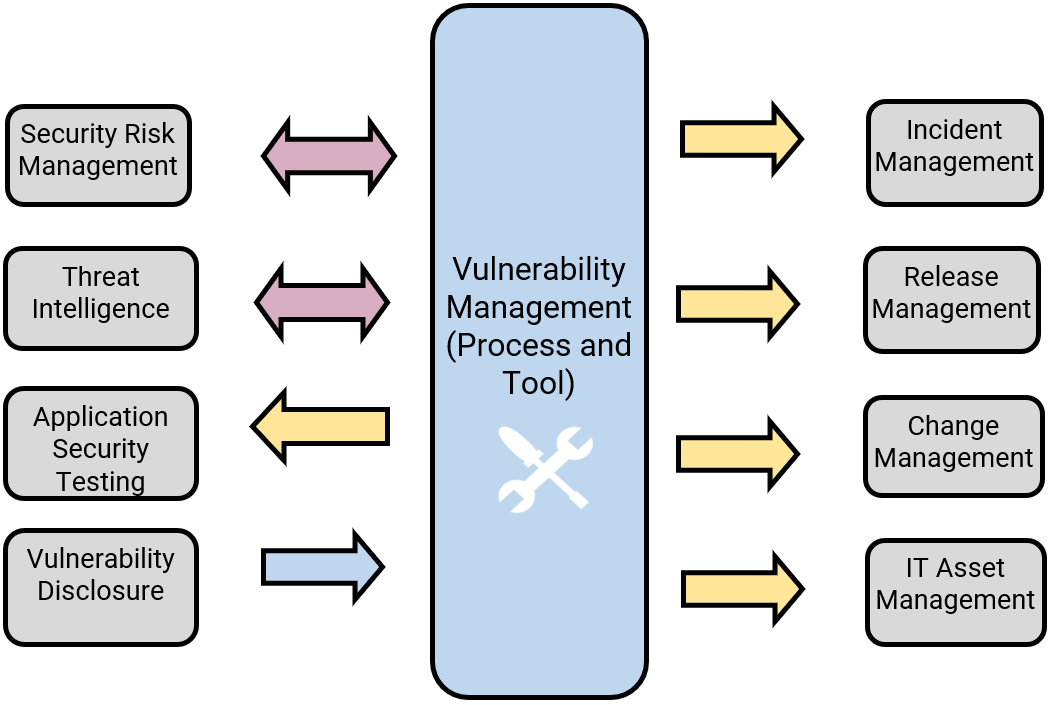

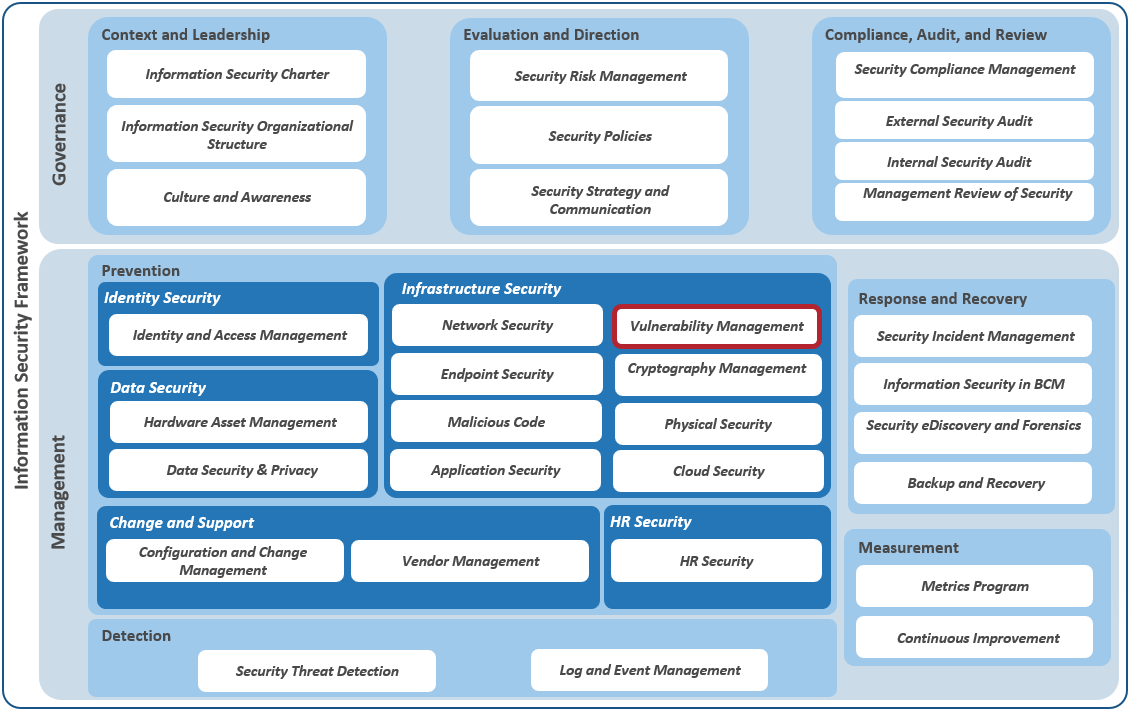

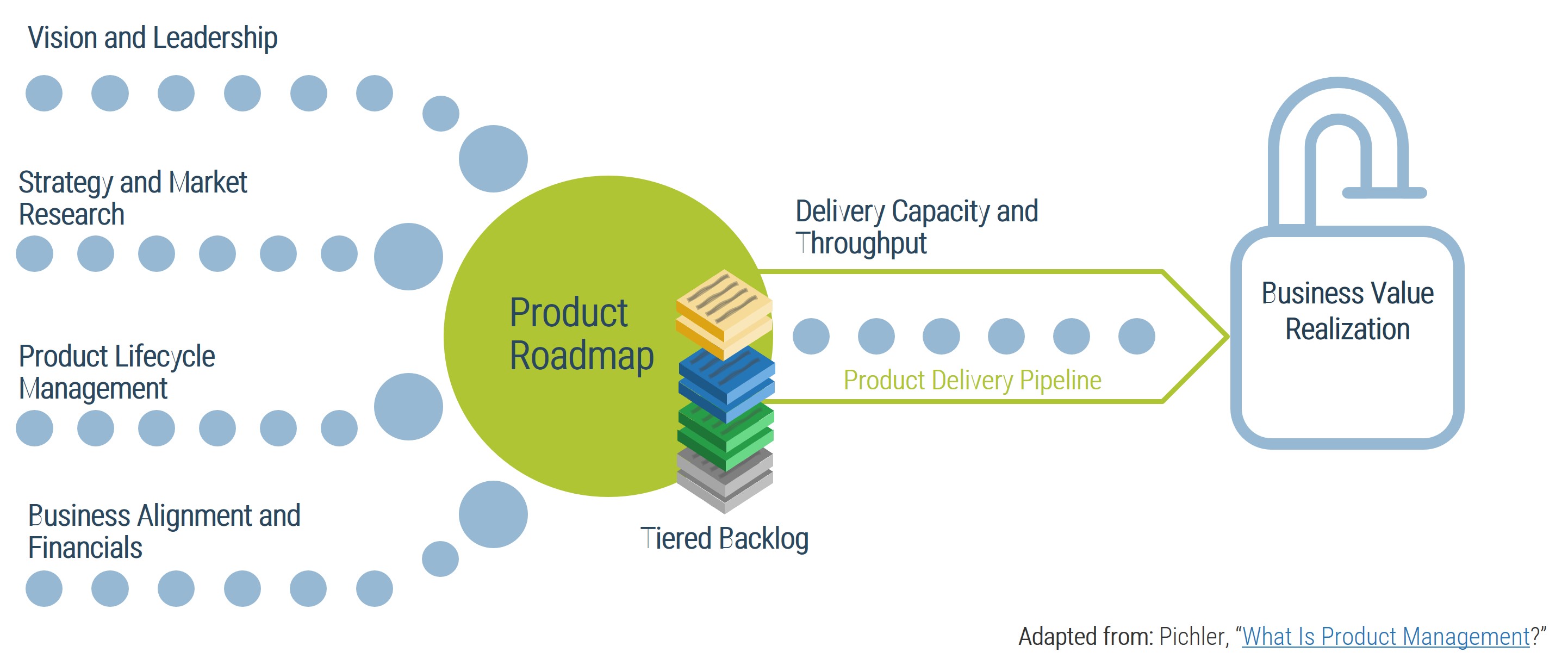

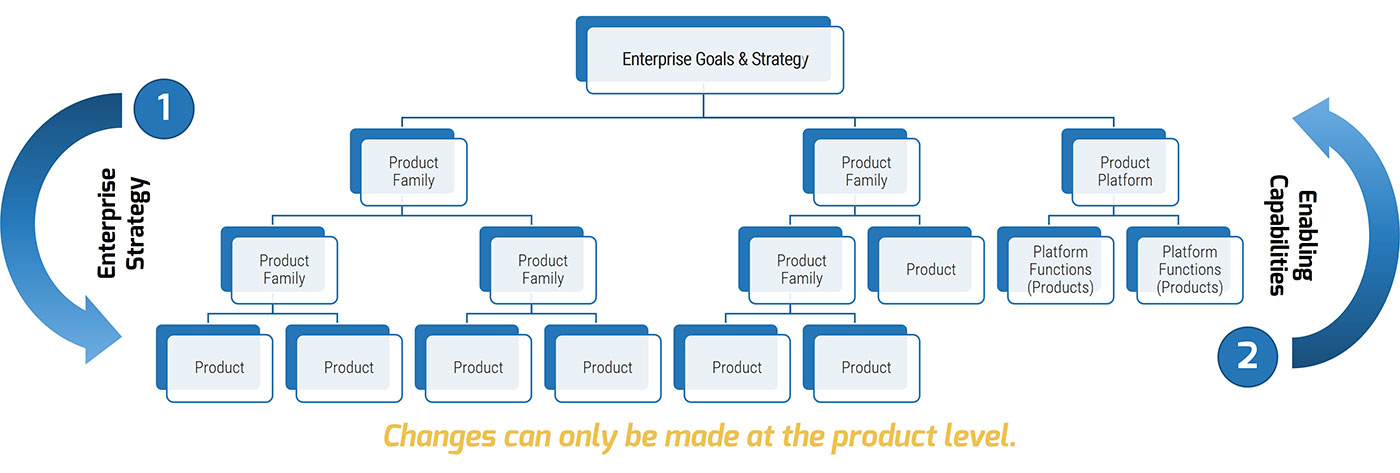

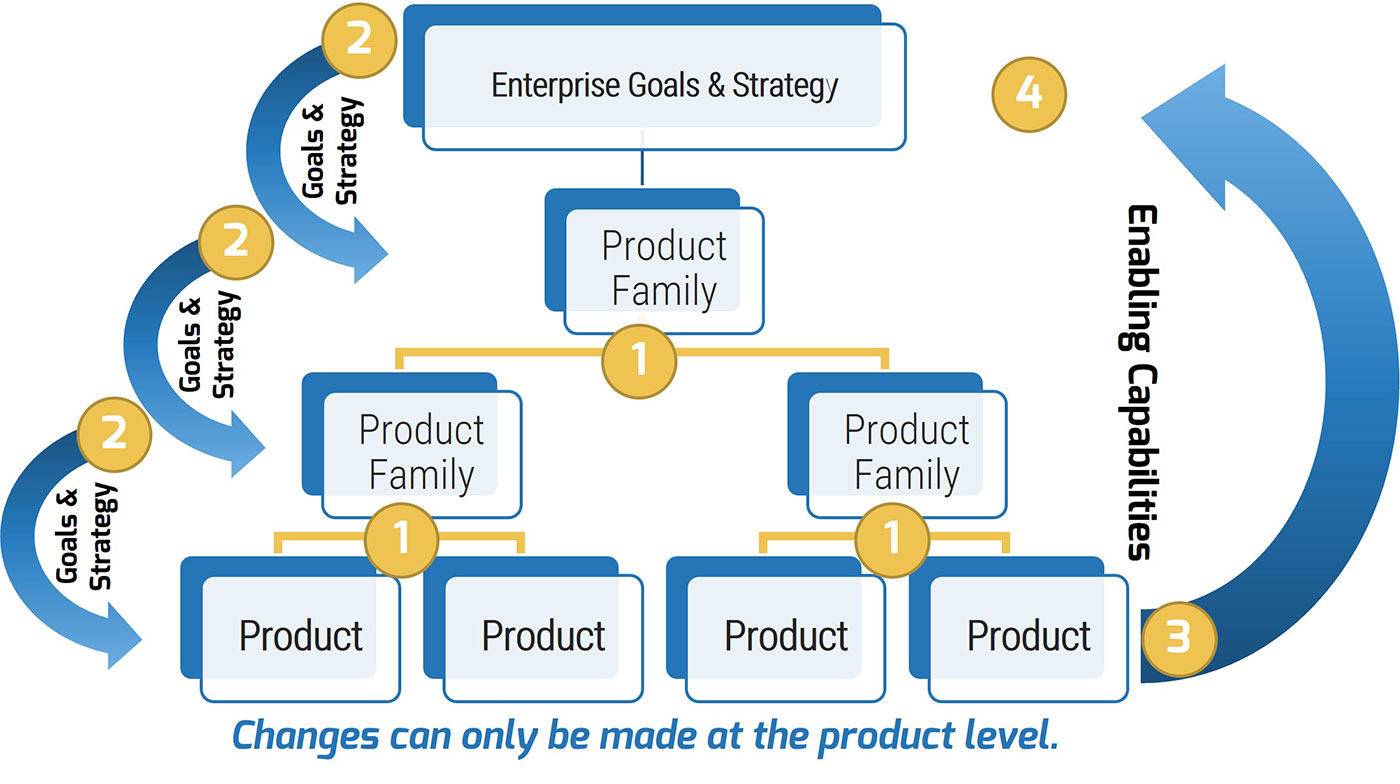

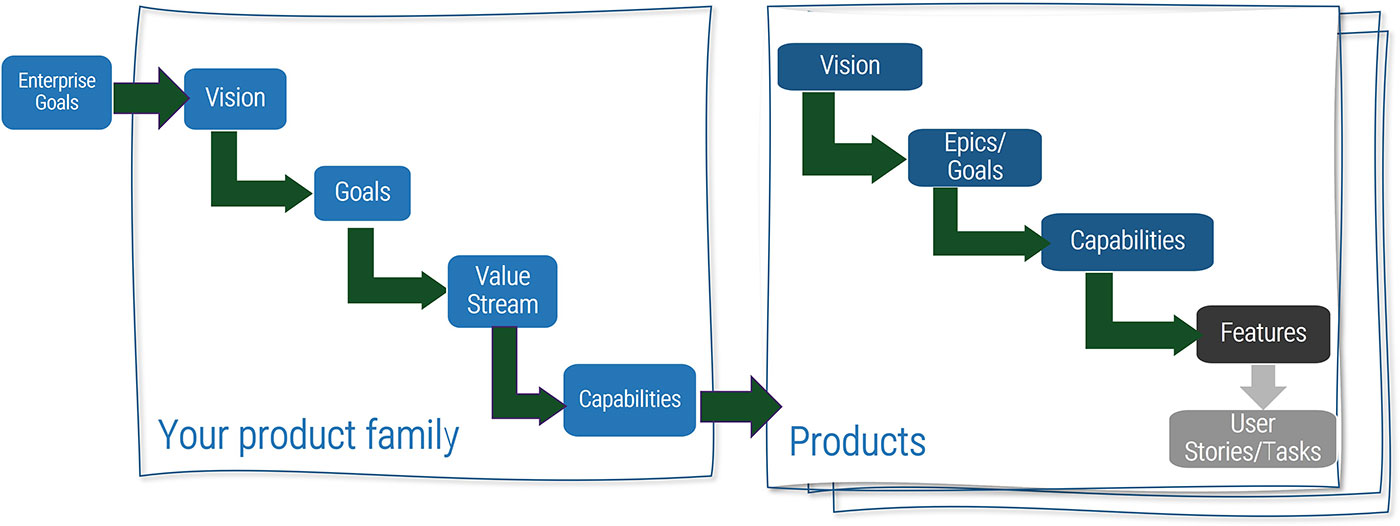

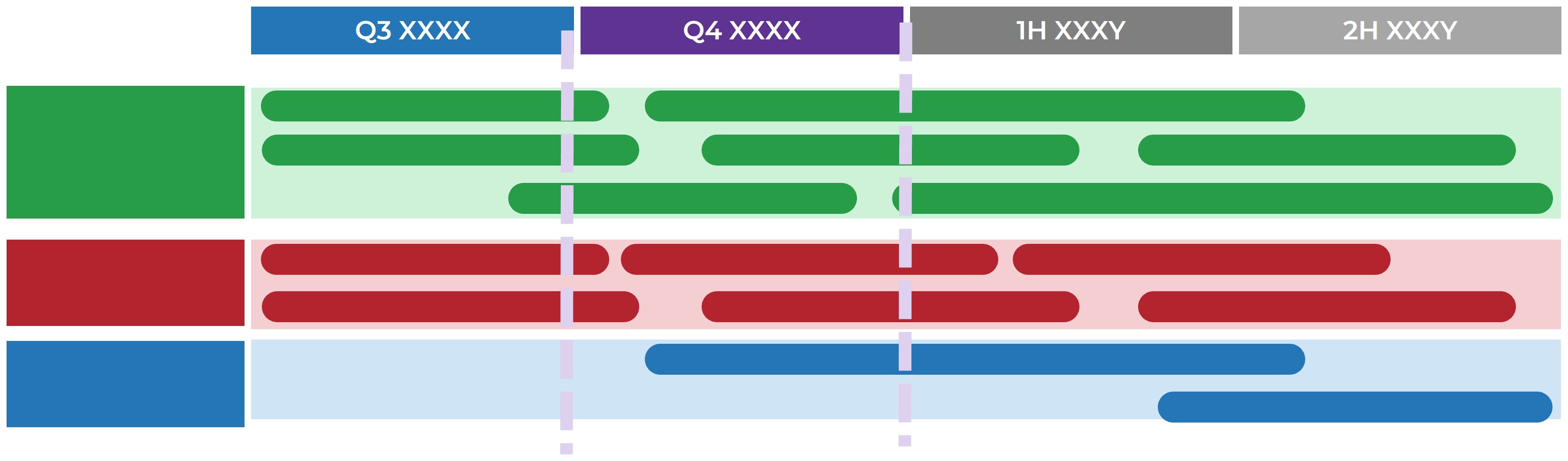

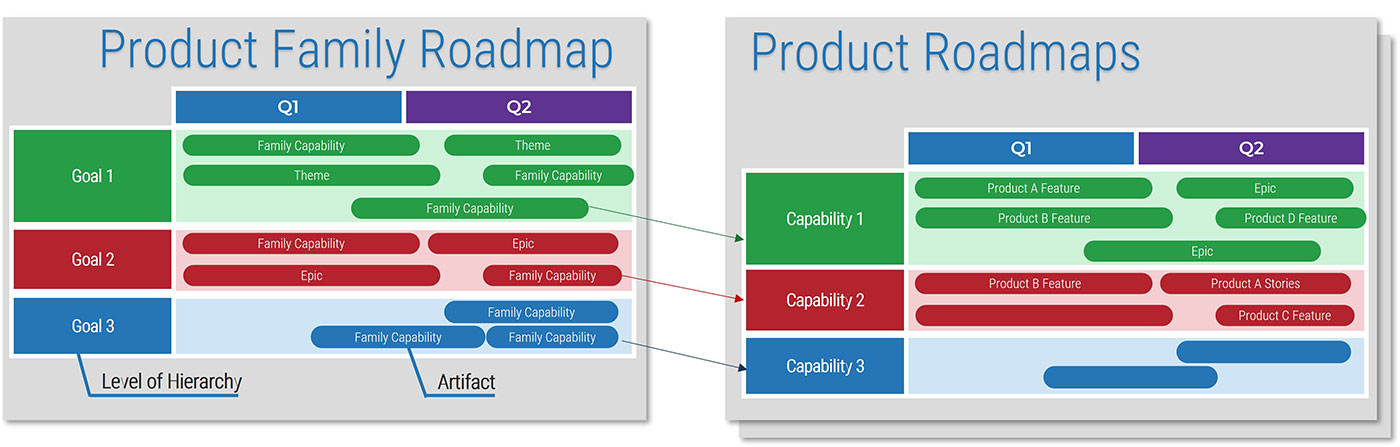

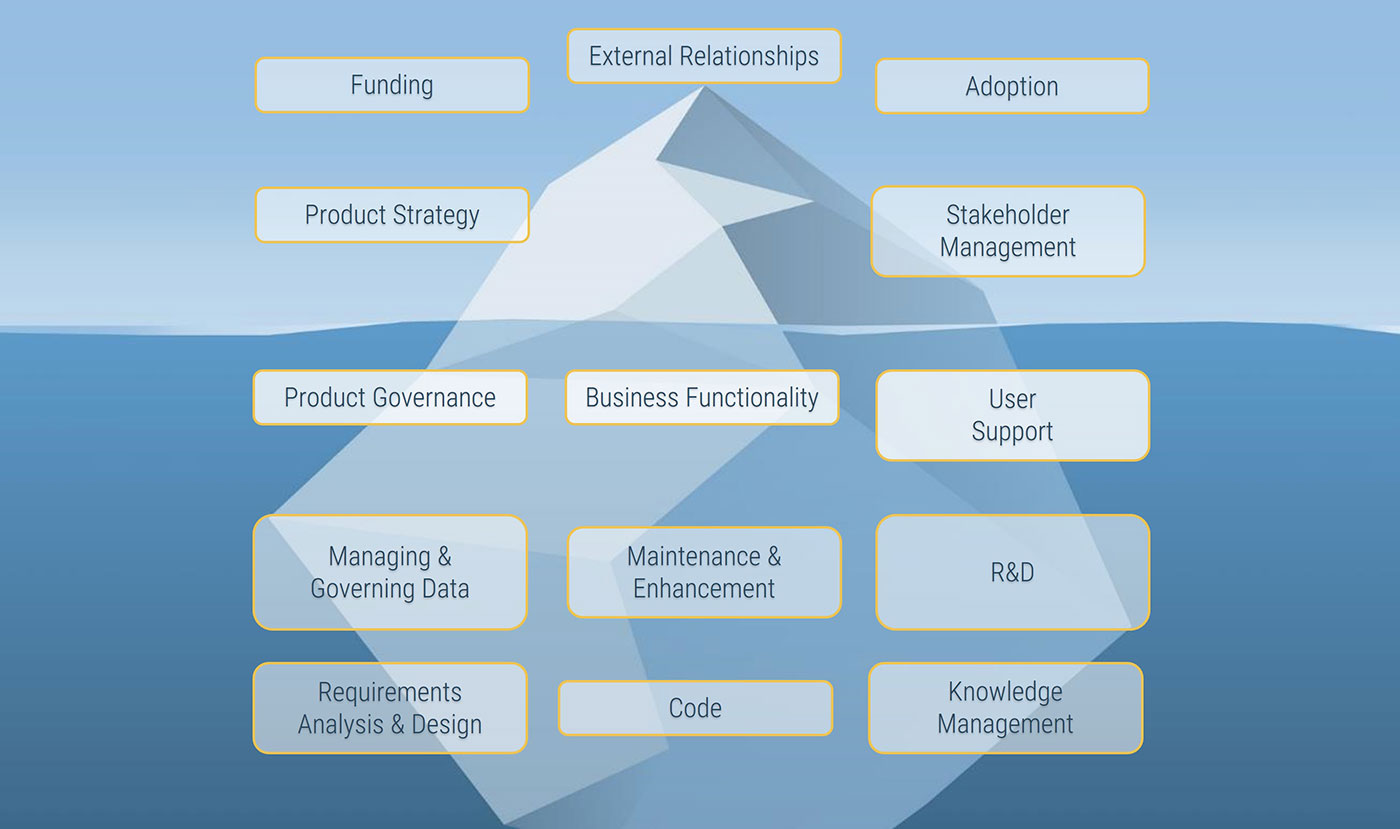

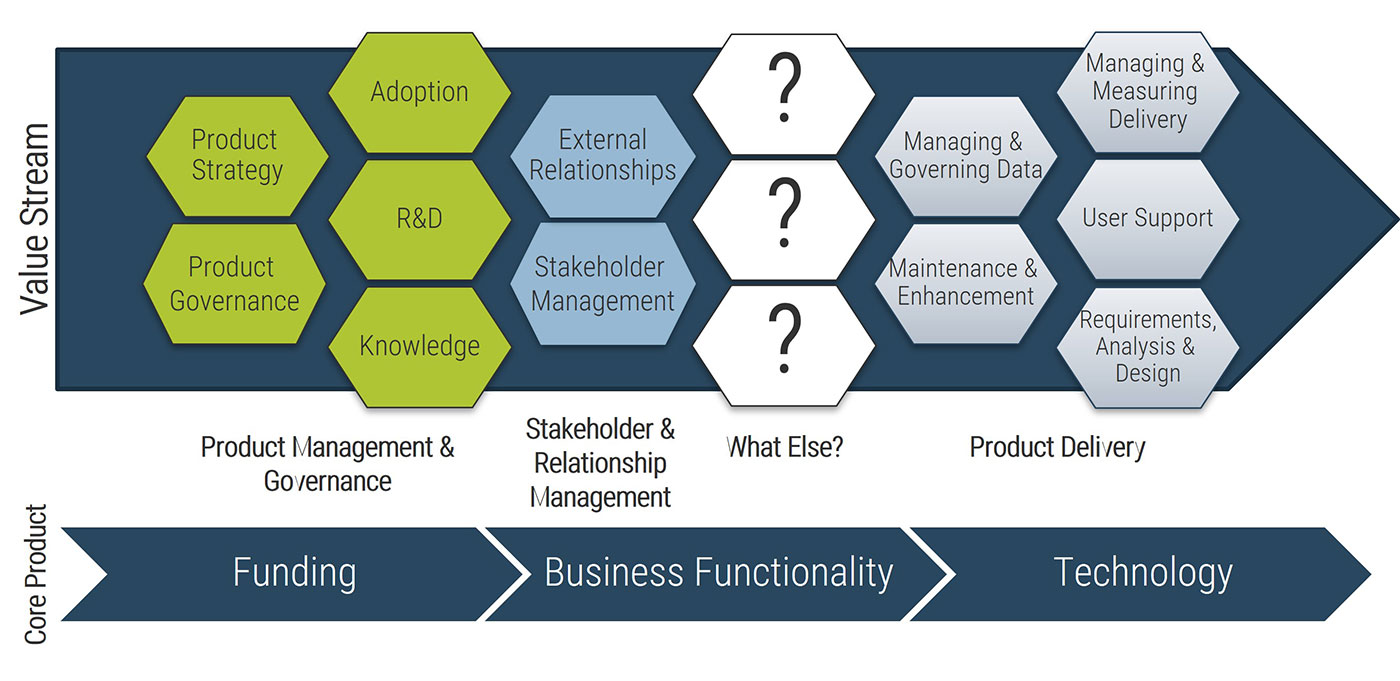

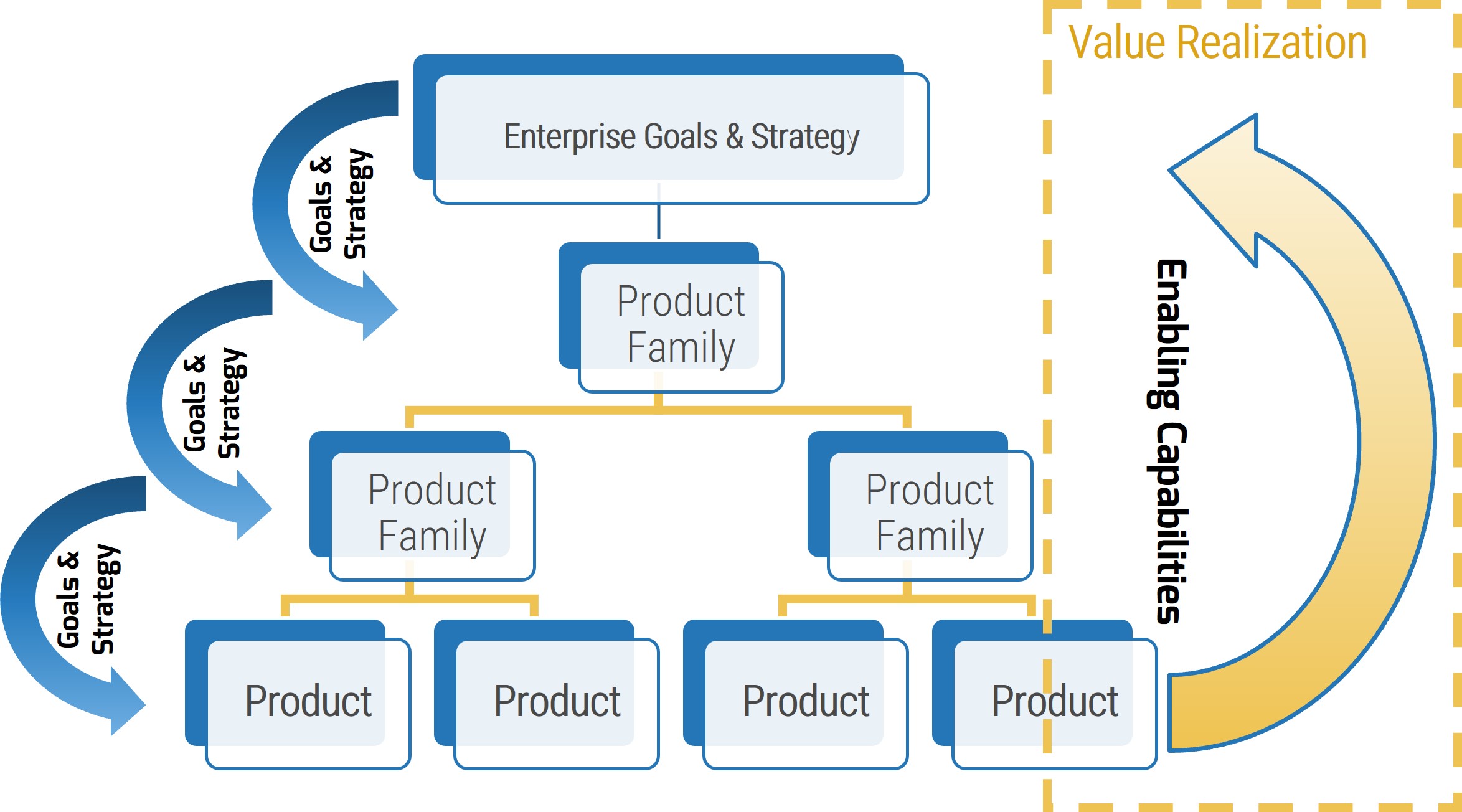

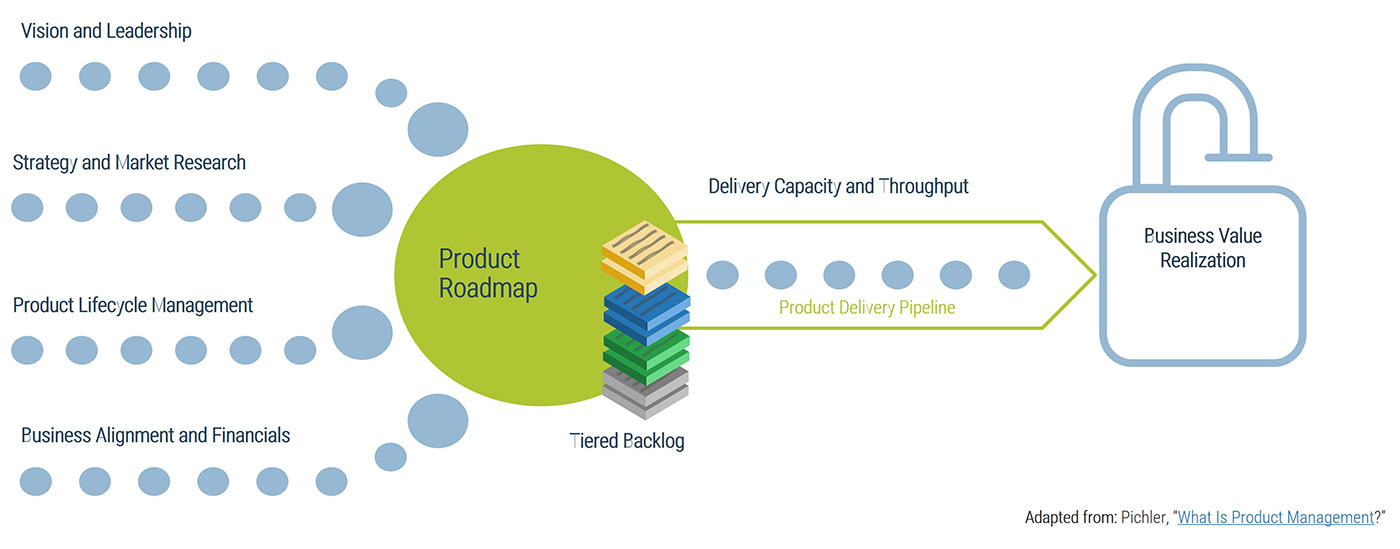

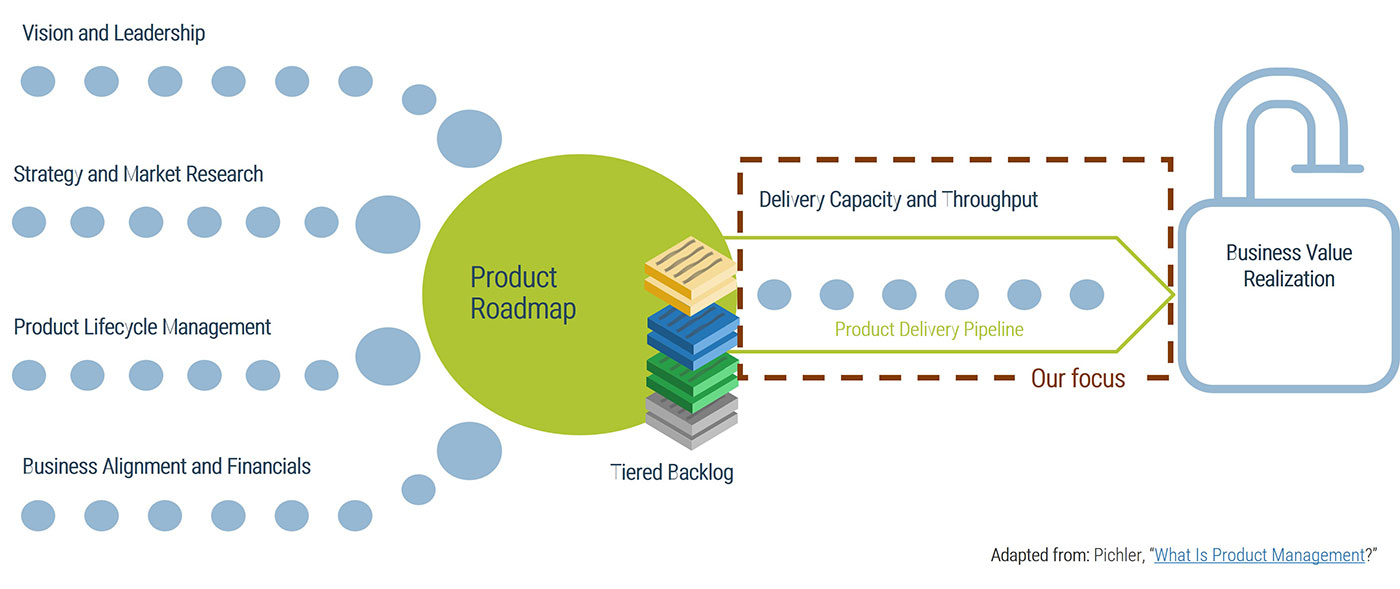

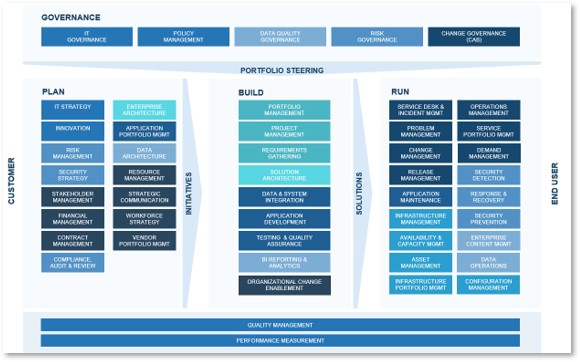

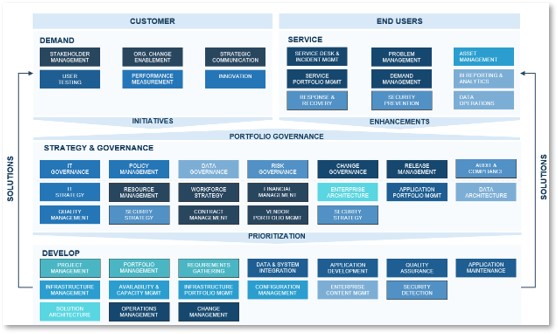

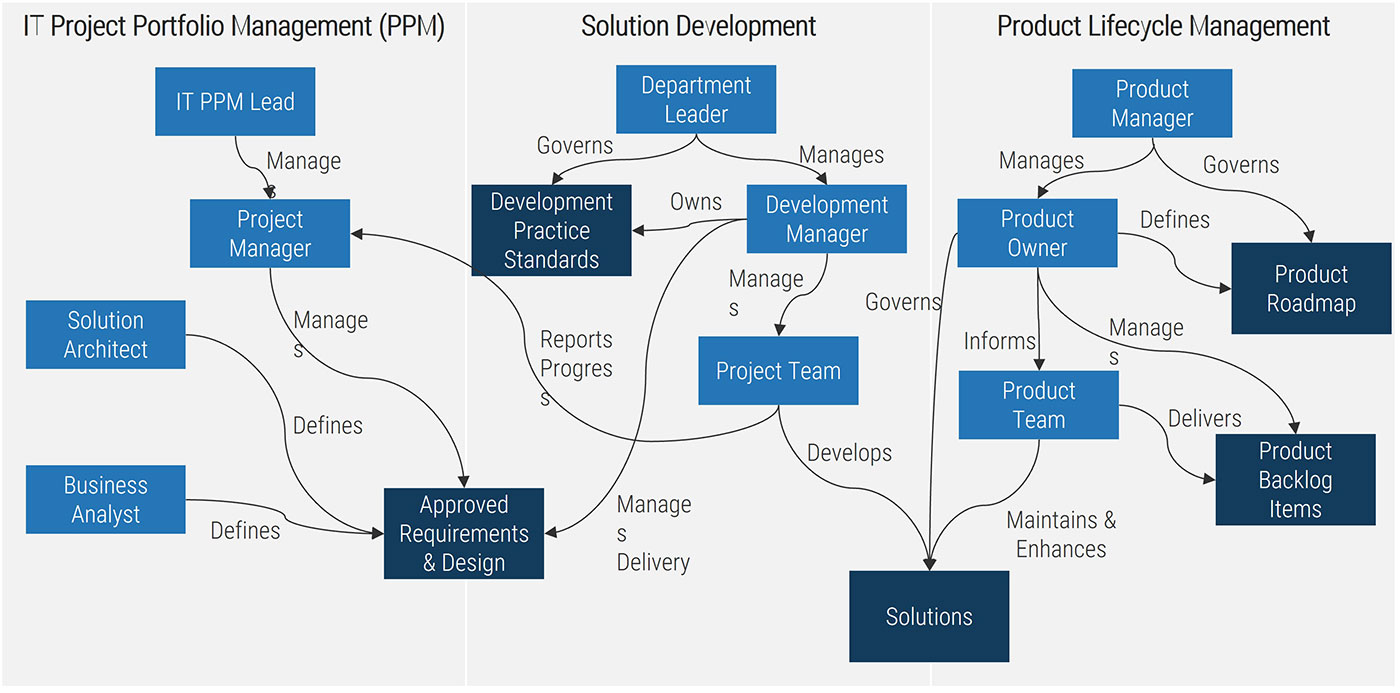

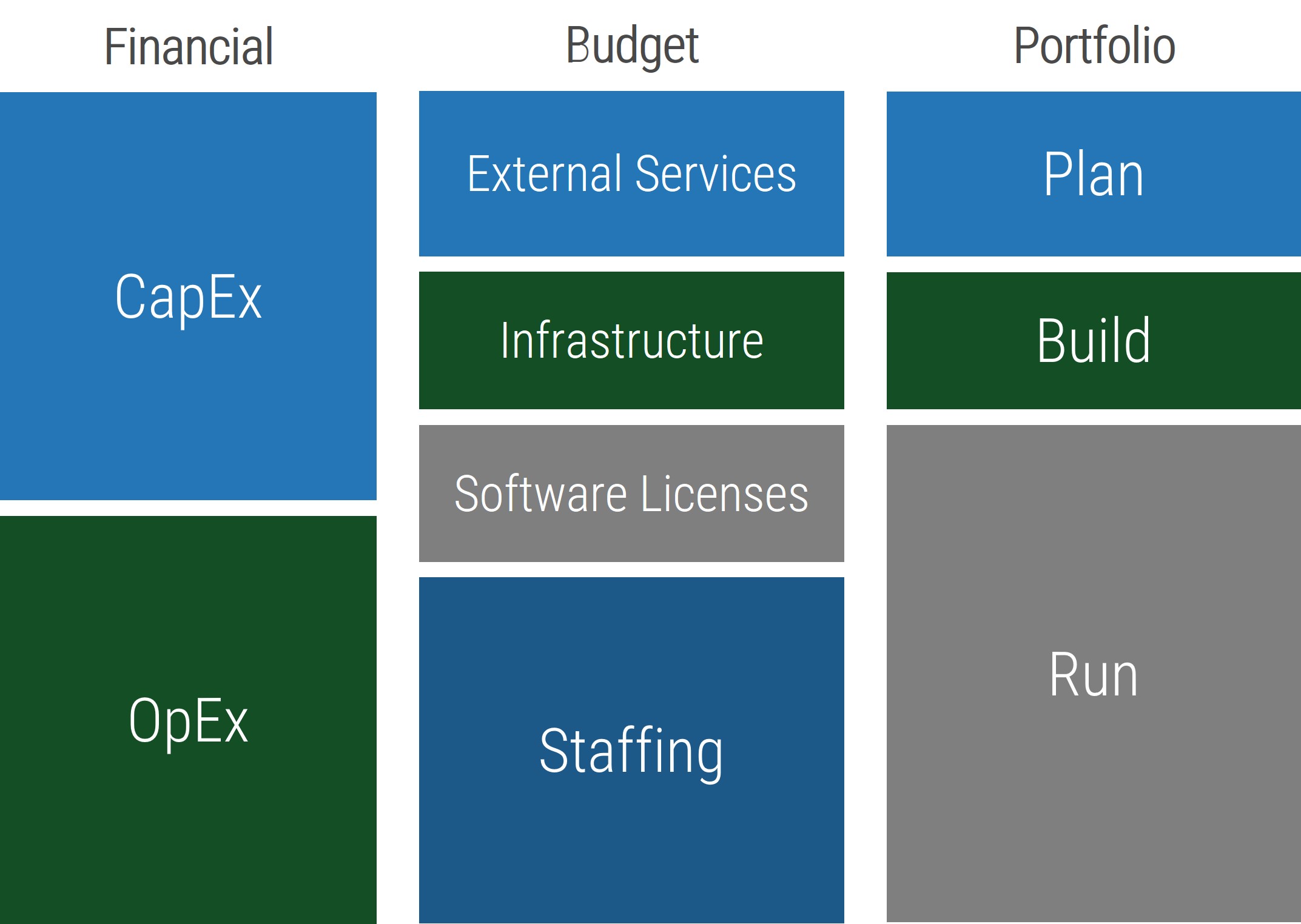

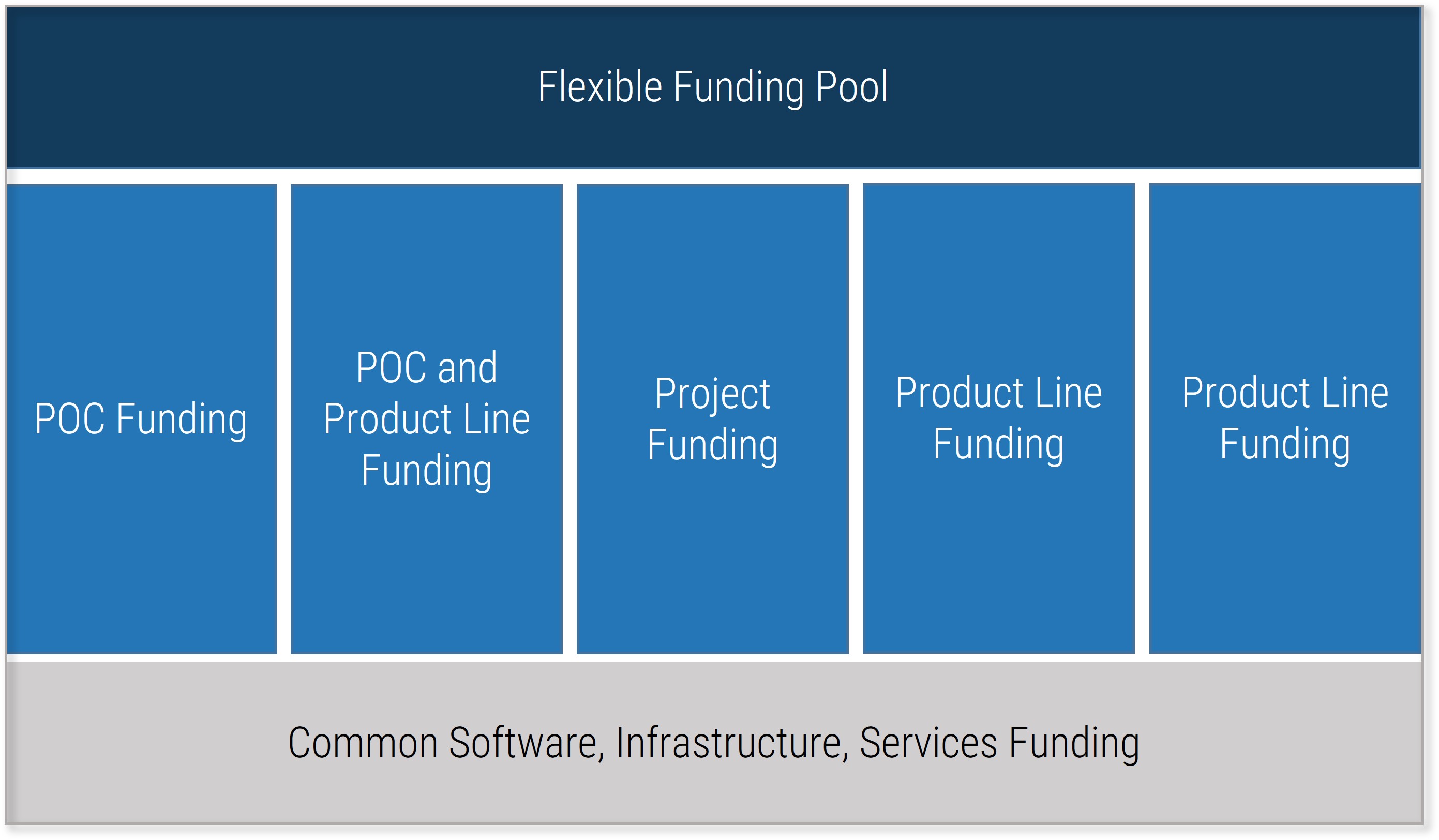

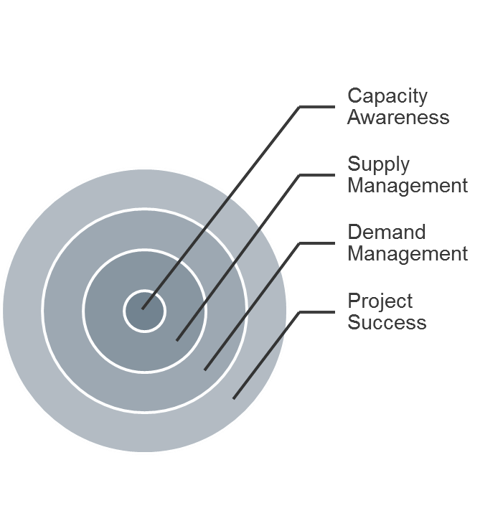

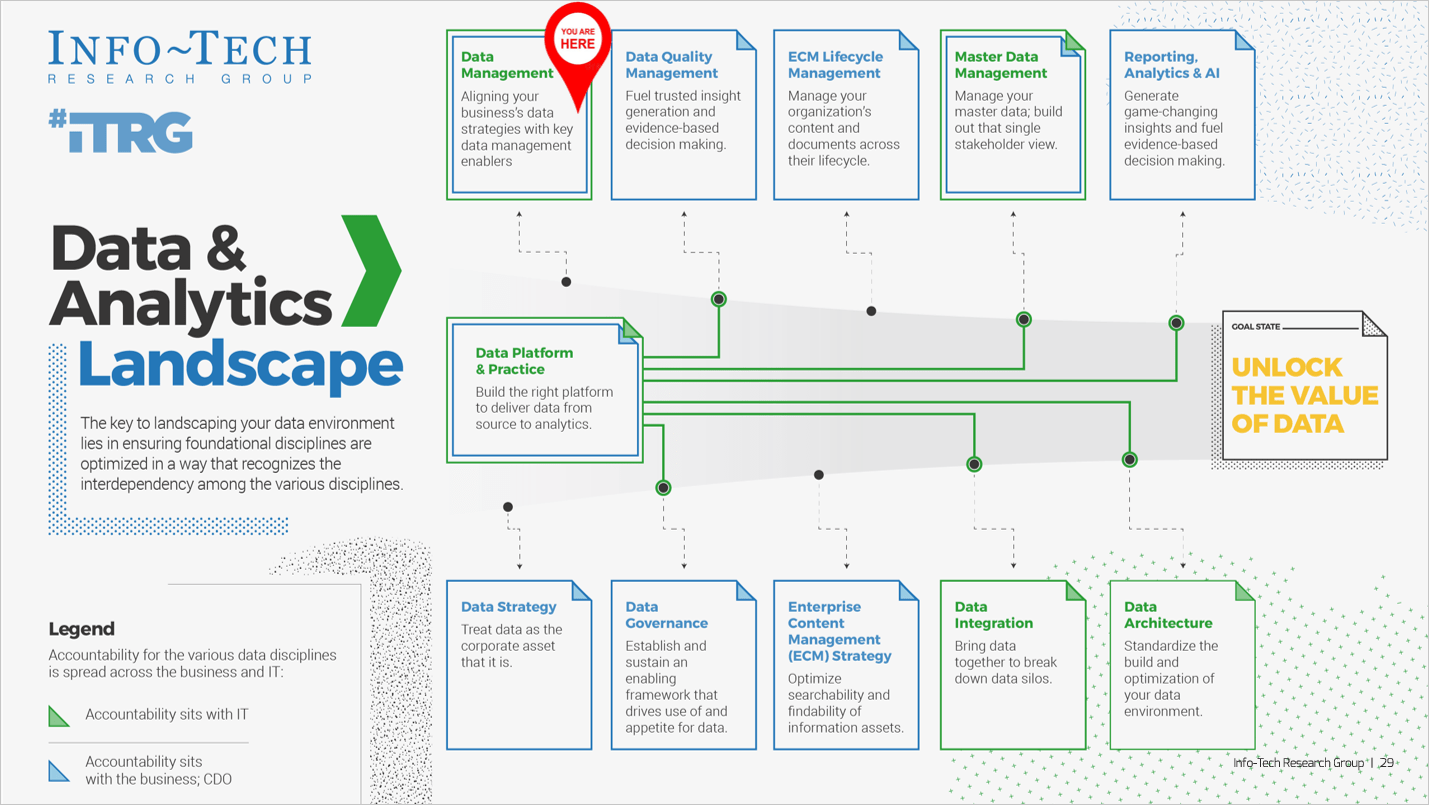

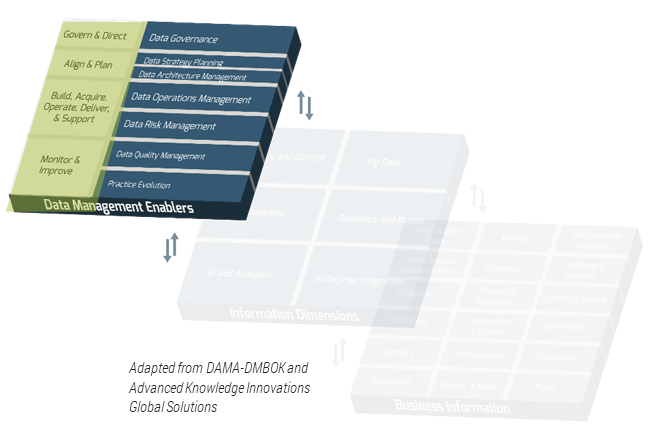

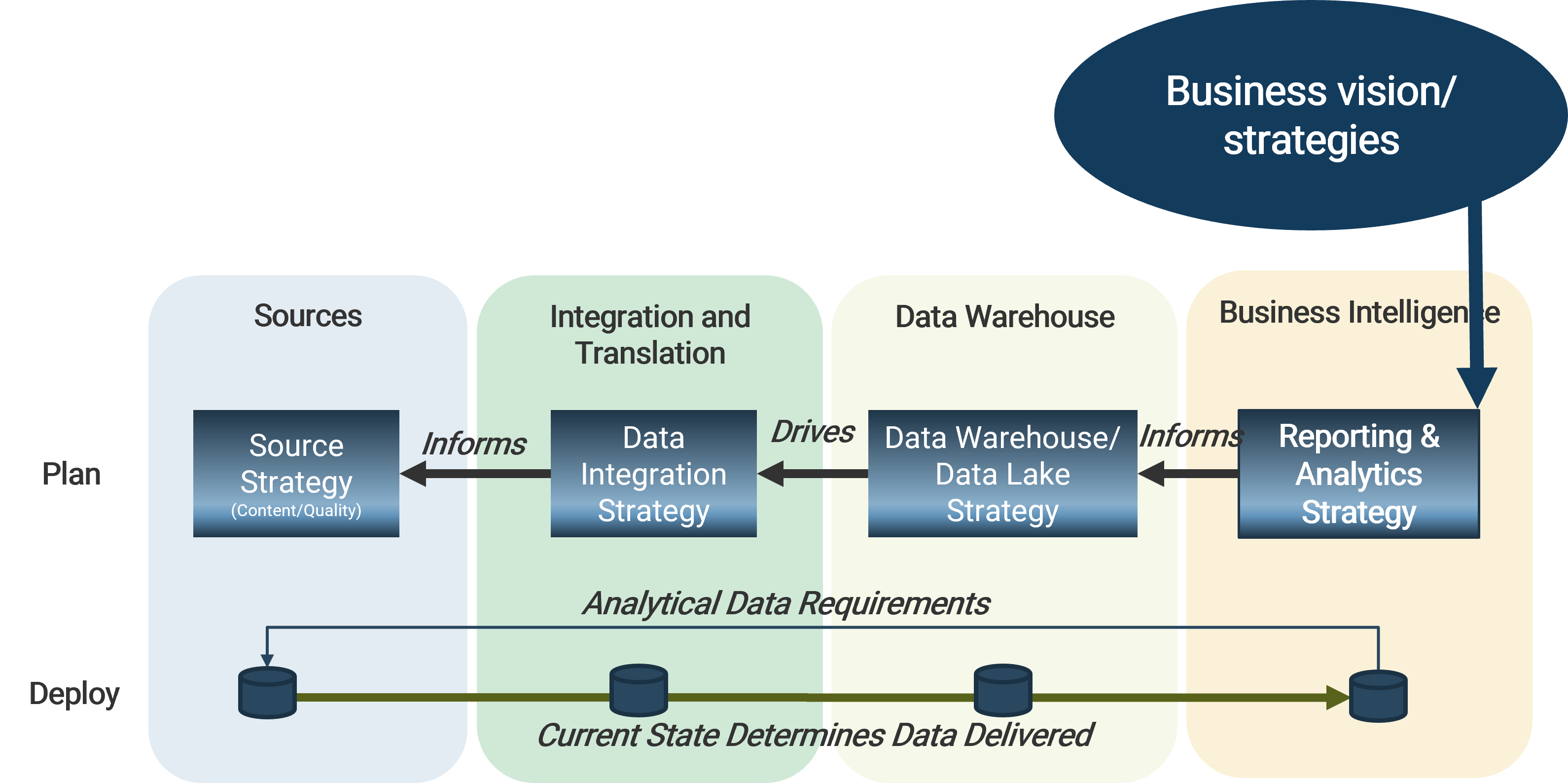

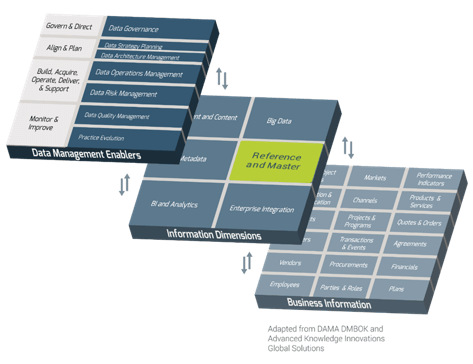

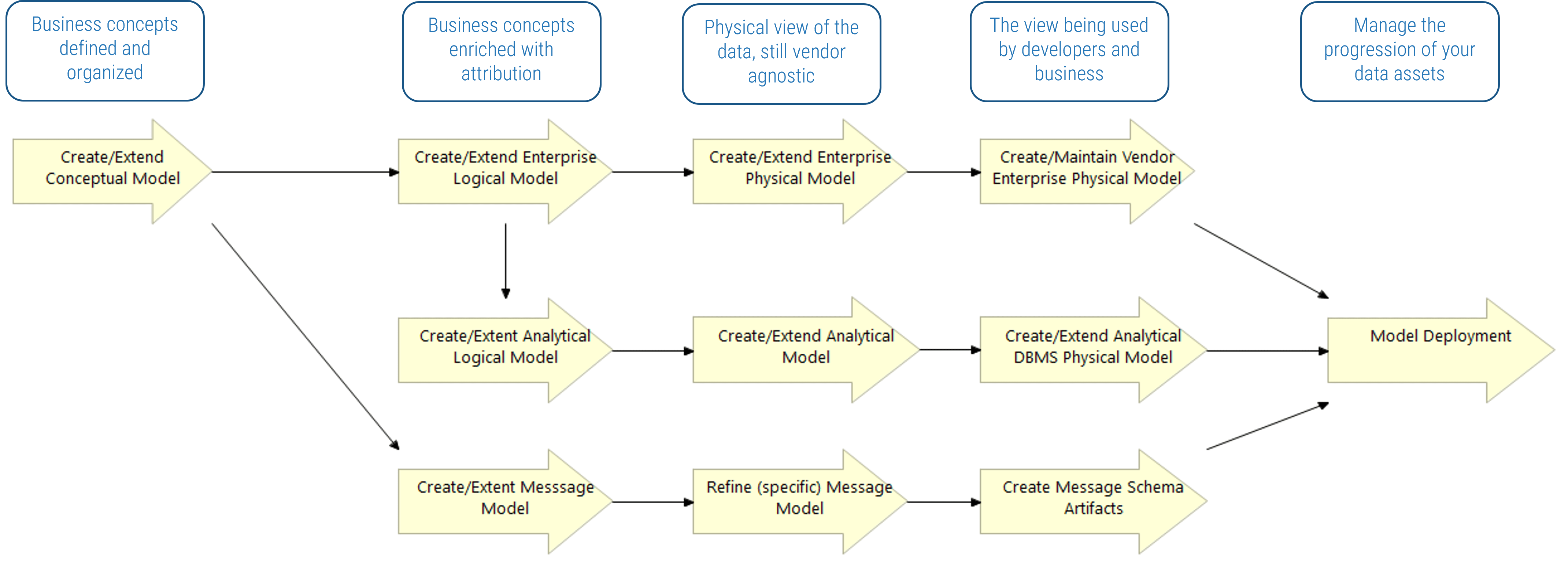

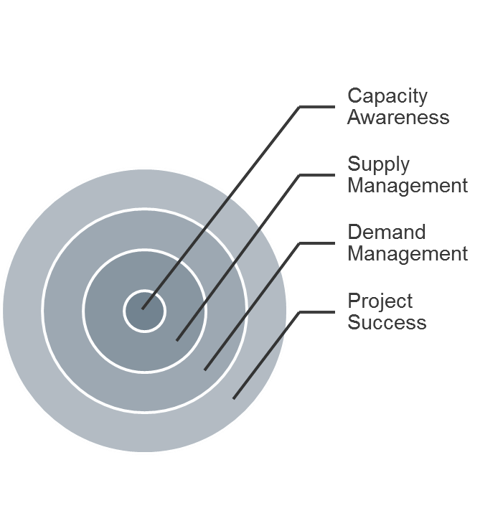

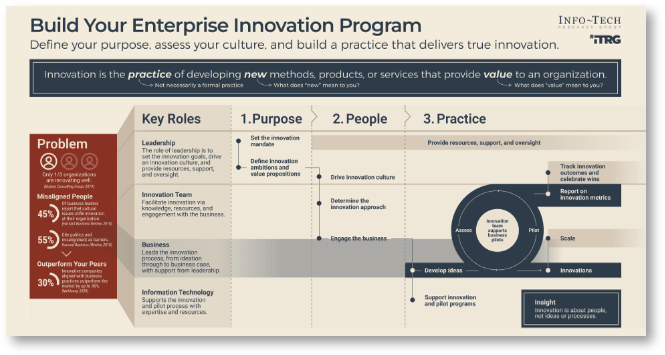

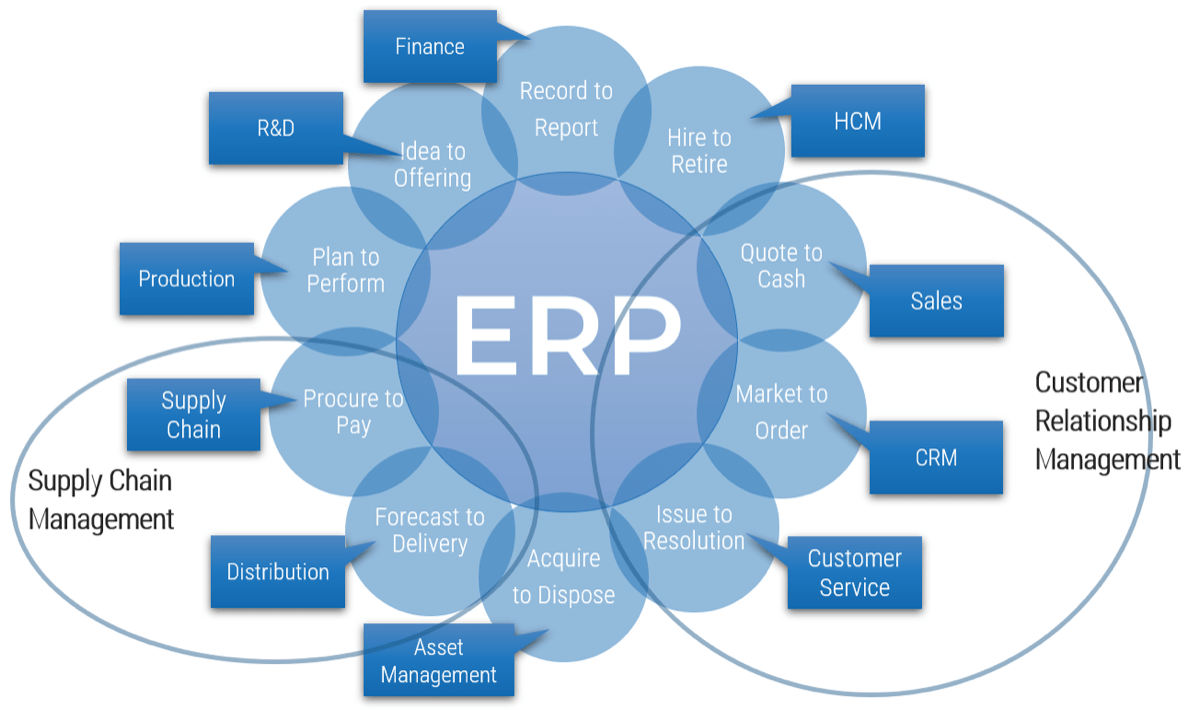

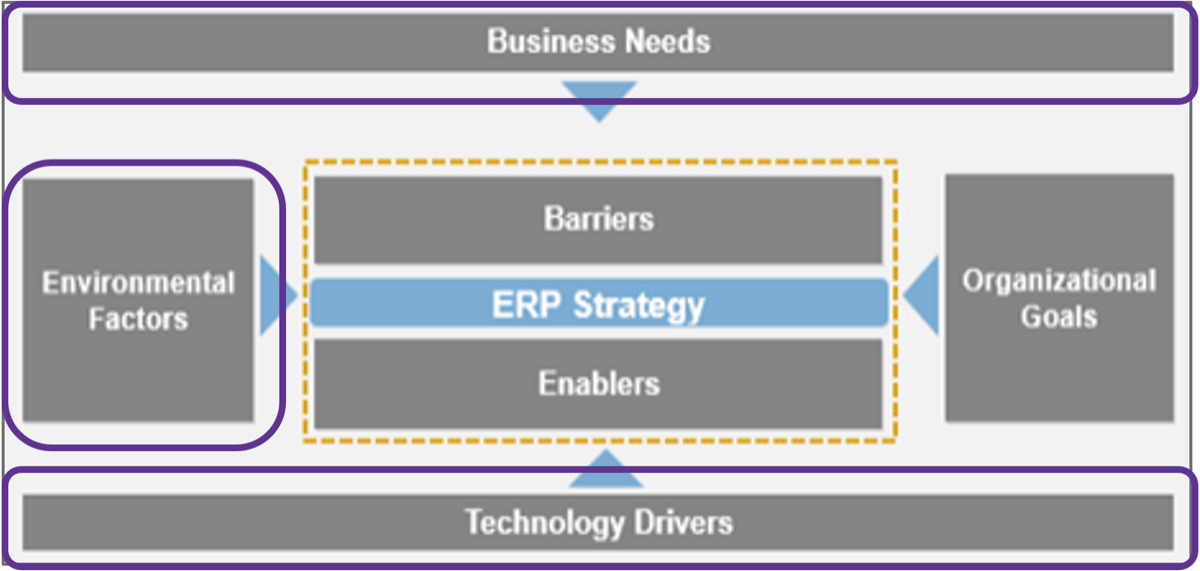

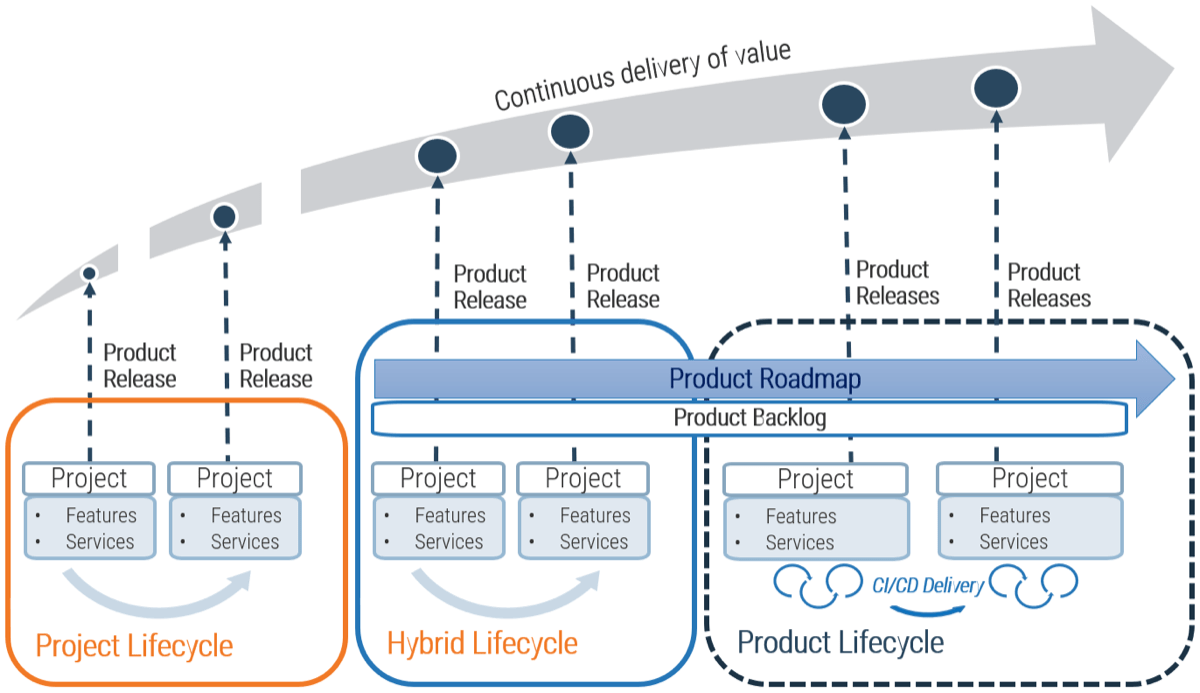

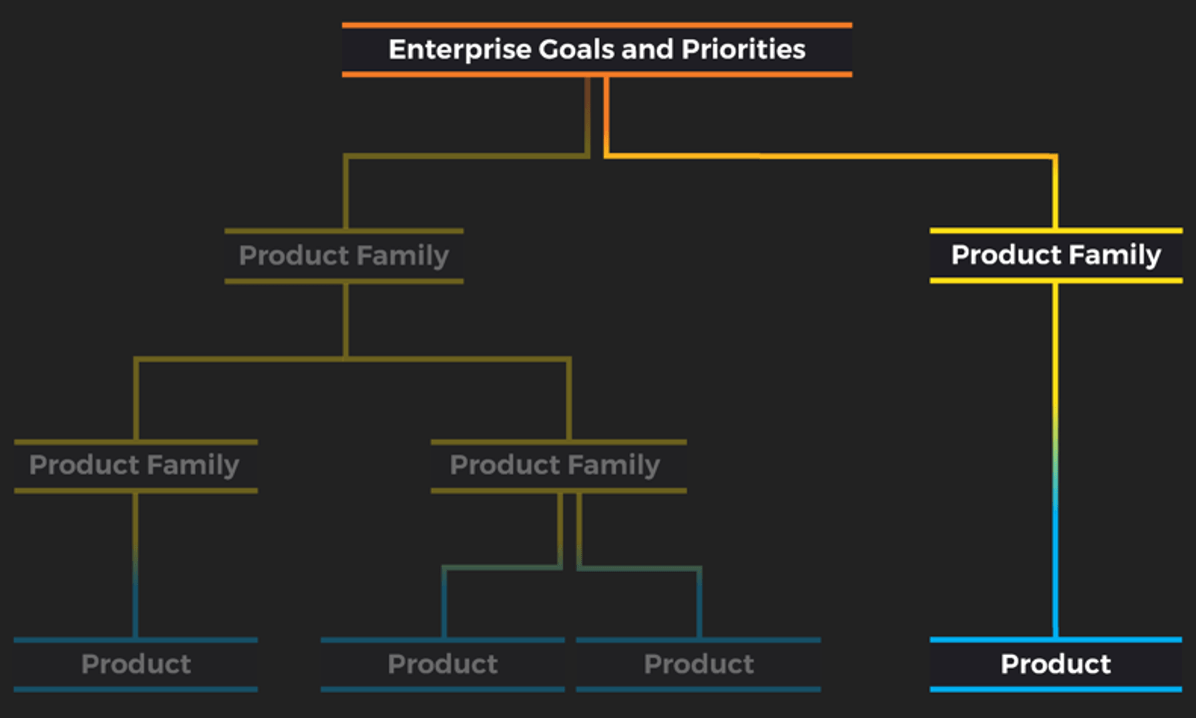

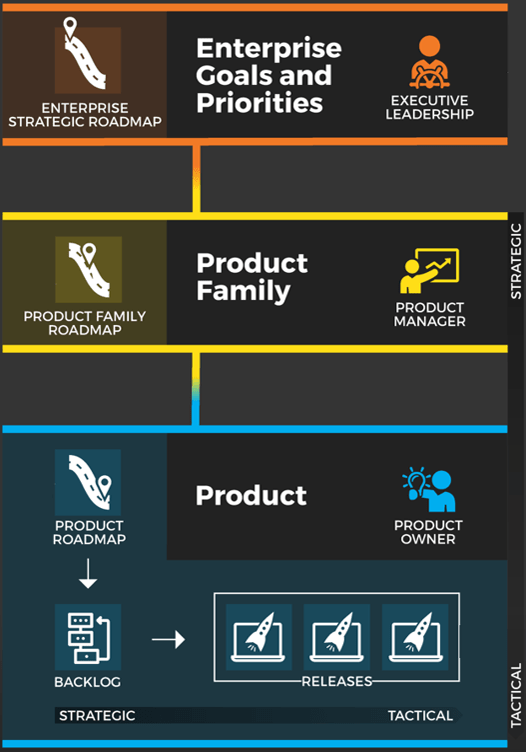

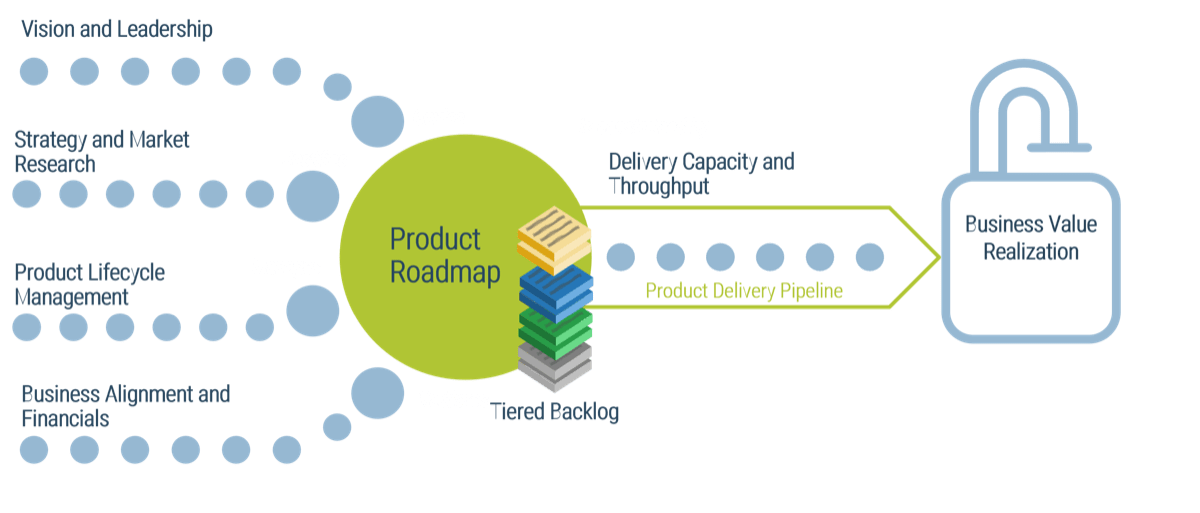

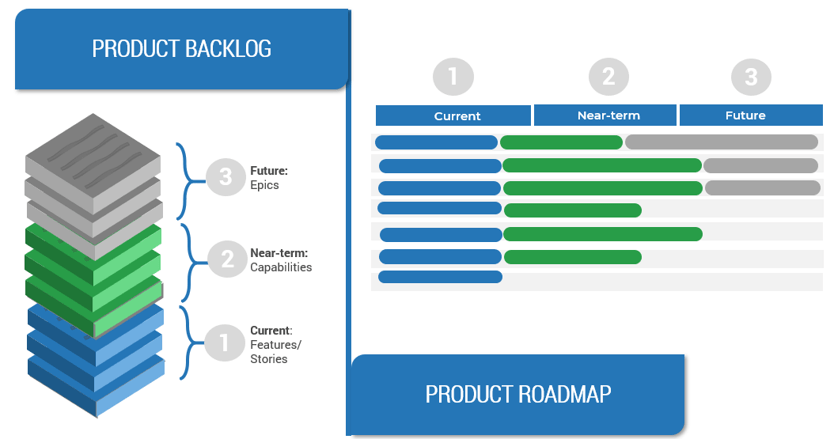

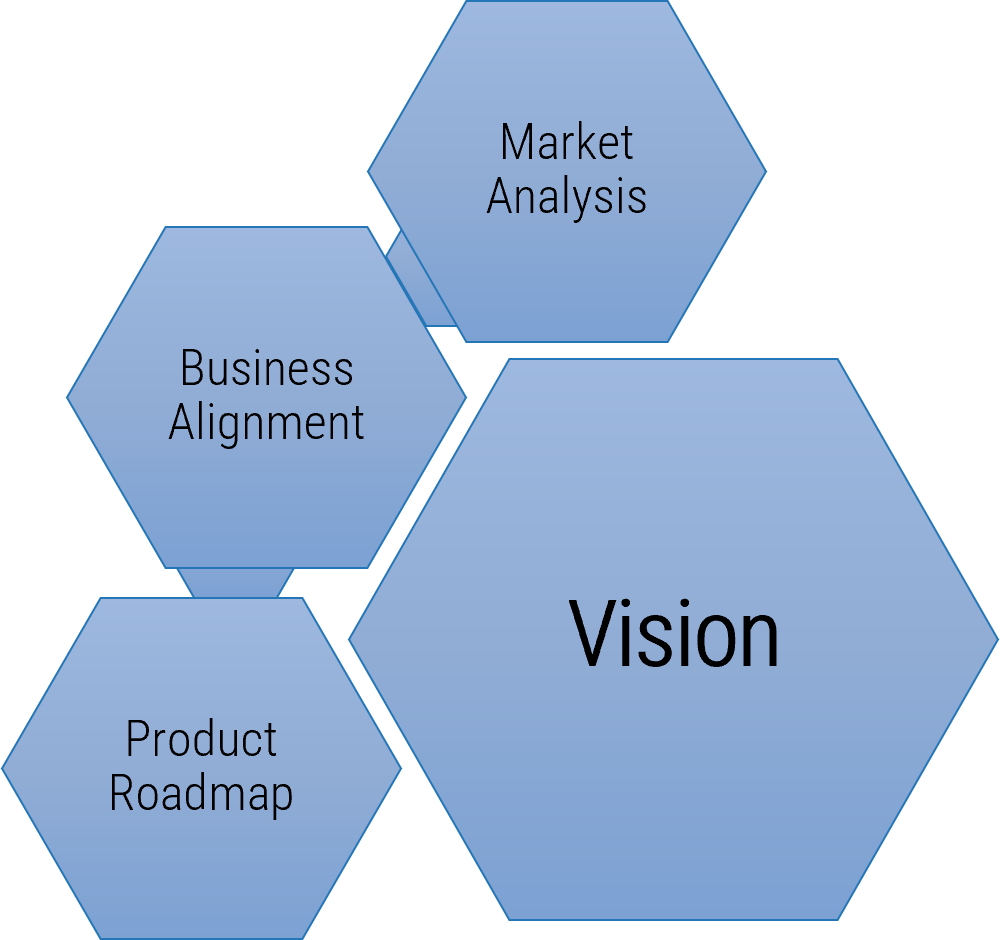

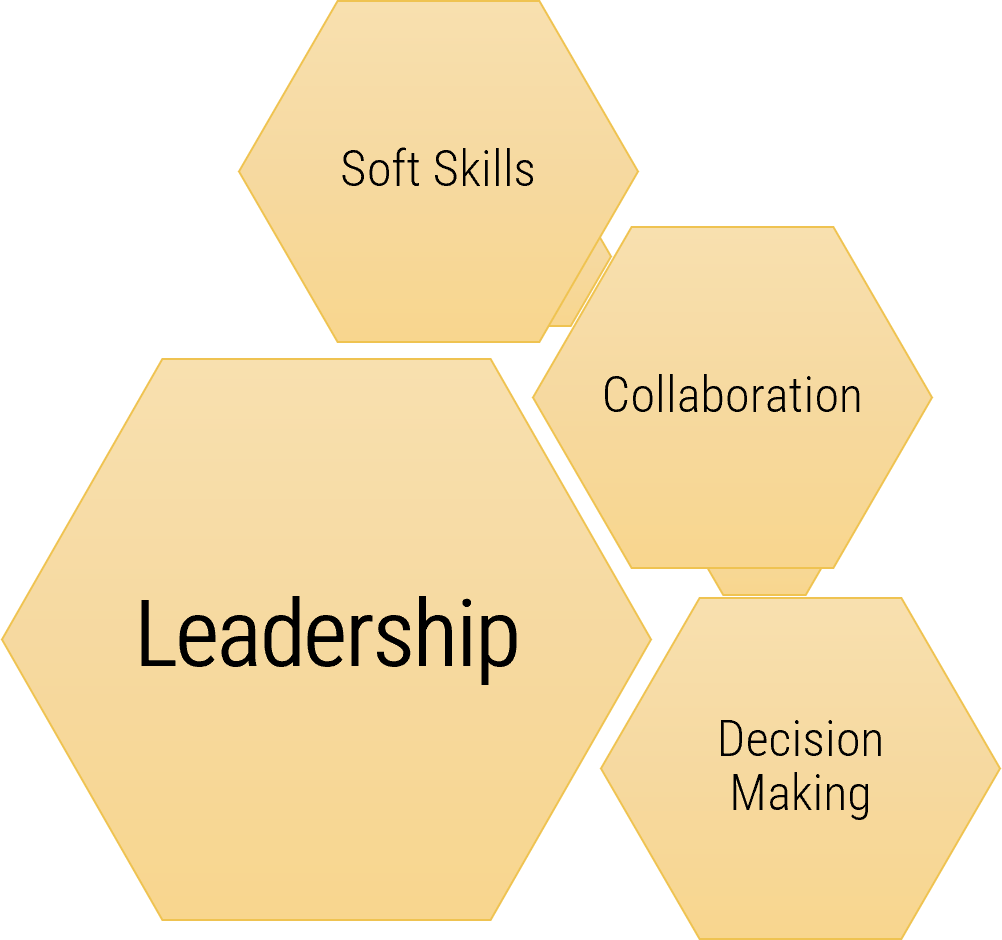

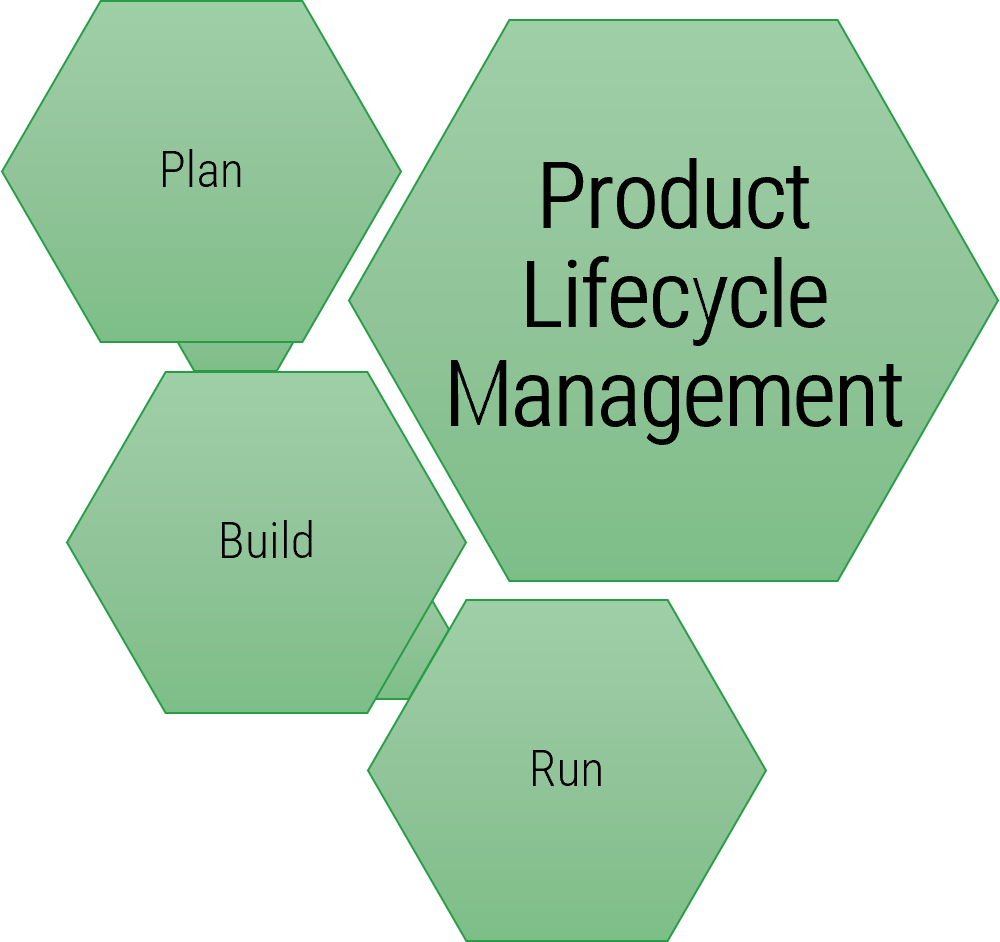

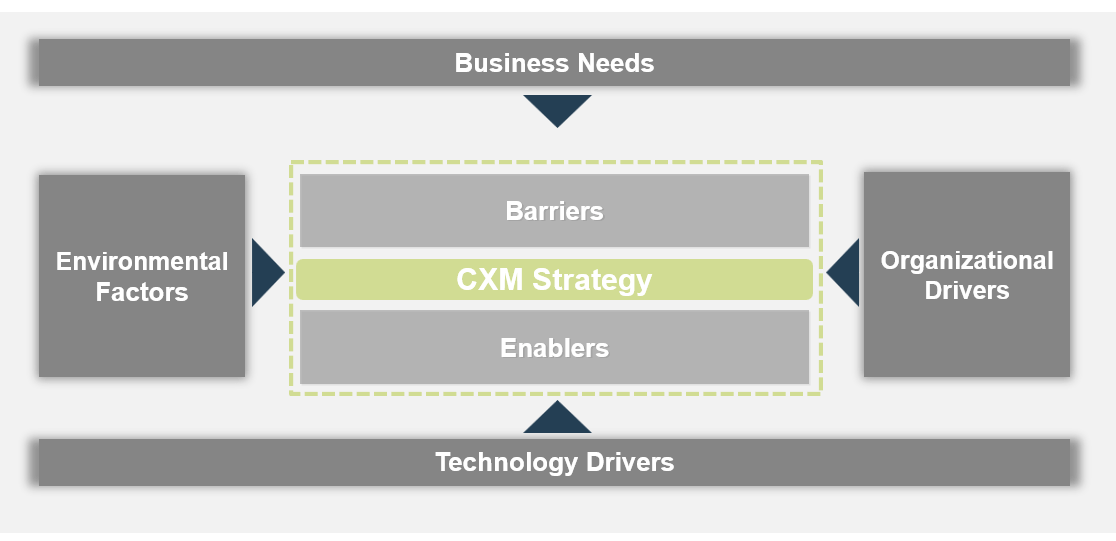

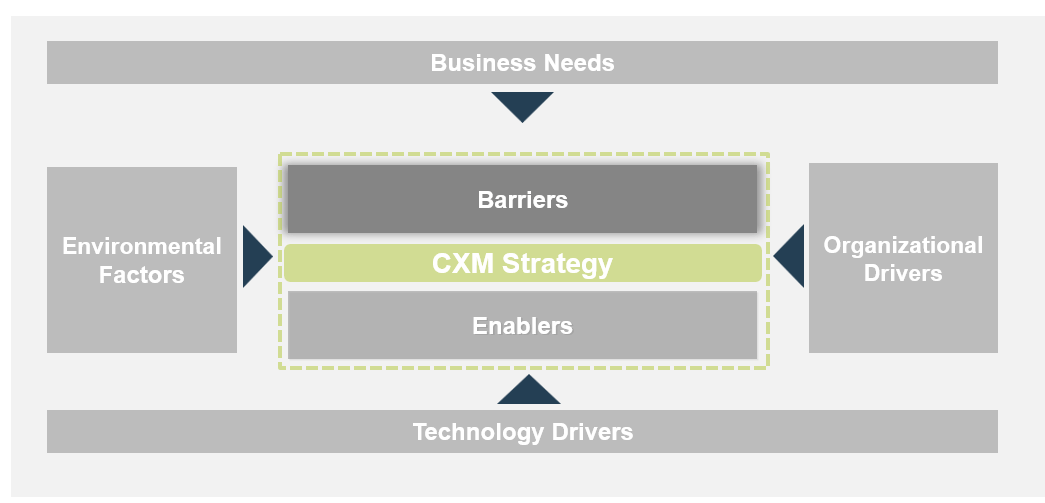

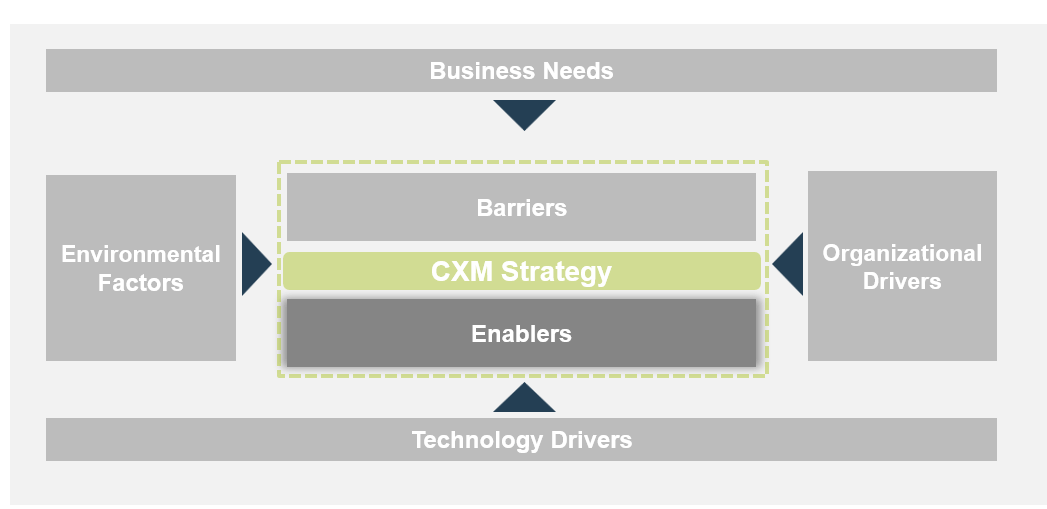

Info-Tech’s approach to resource management is part of our larger project portfolio management framework

This blueprint will help you master the art of resource management and set you up for greater success in other project portfolio management capabilities.

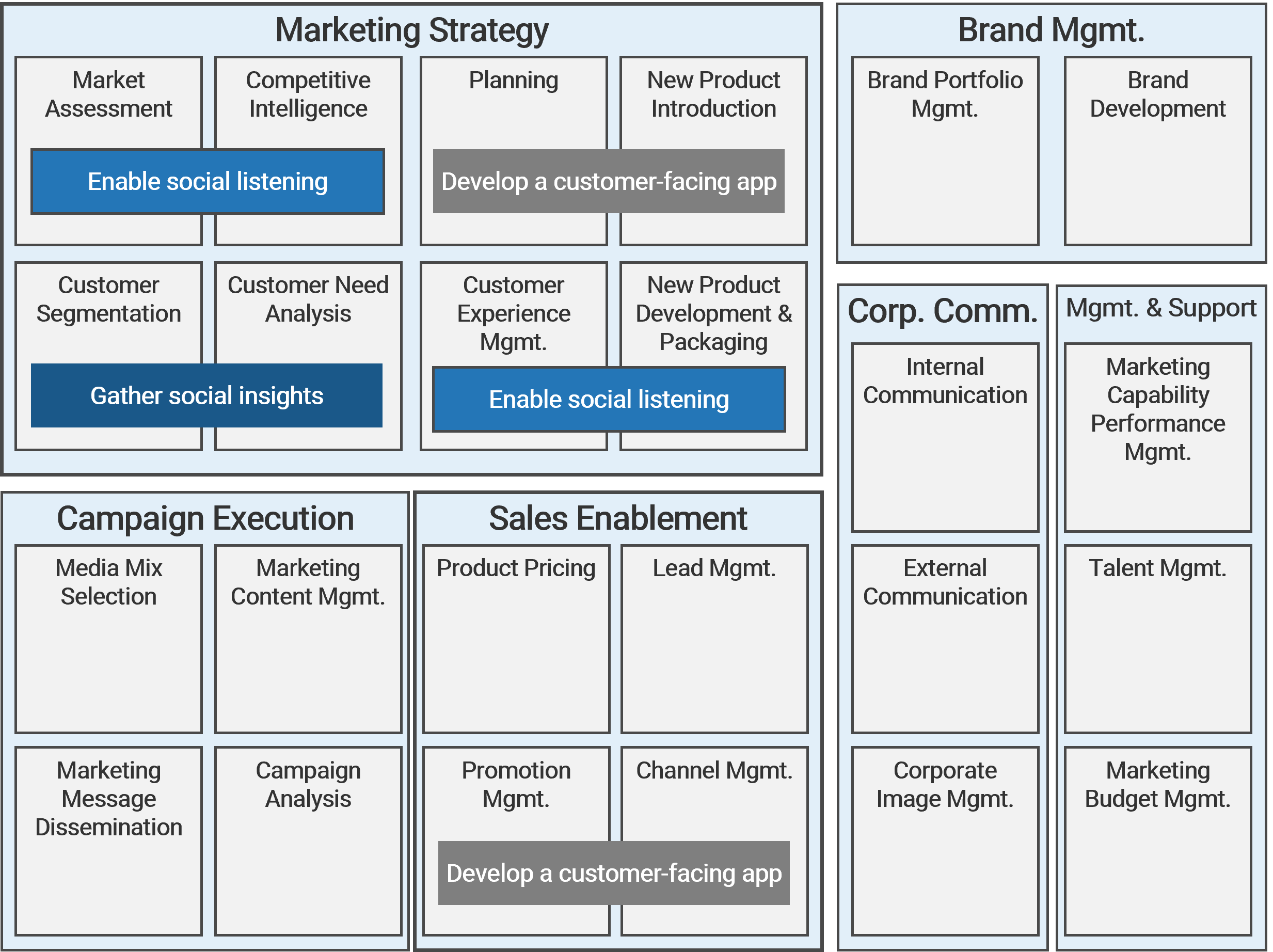

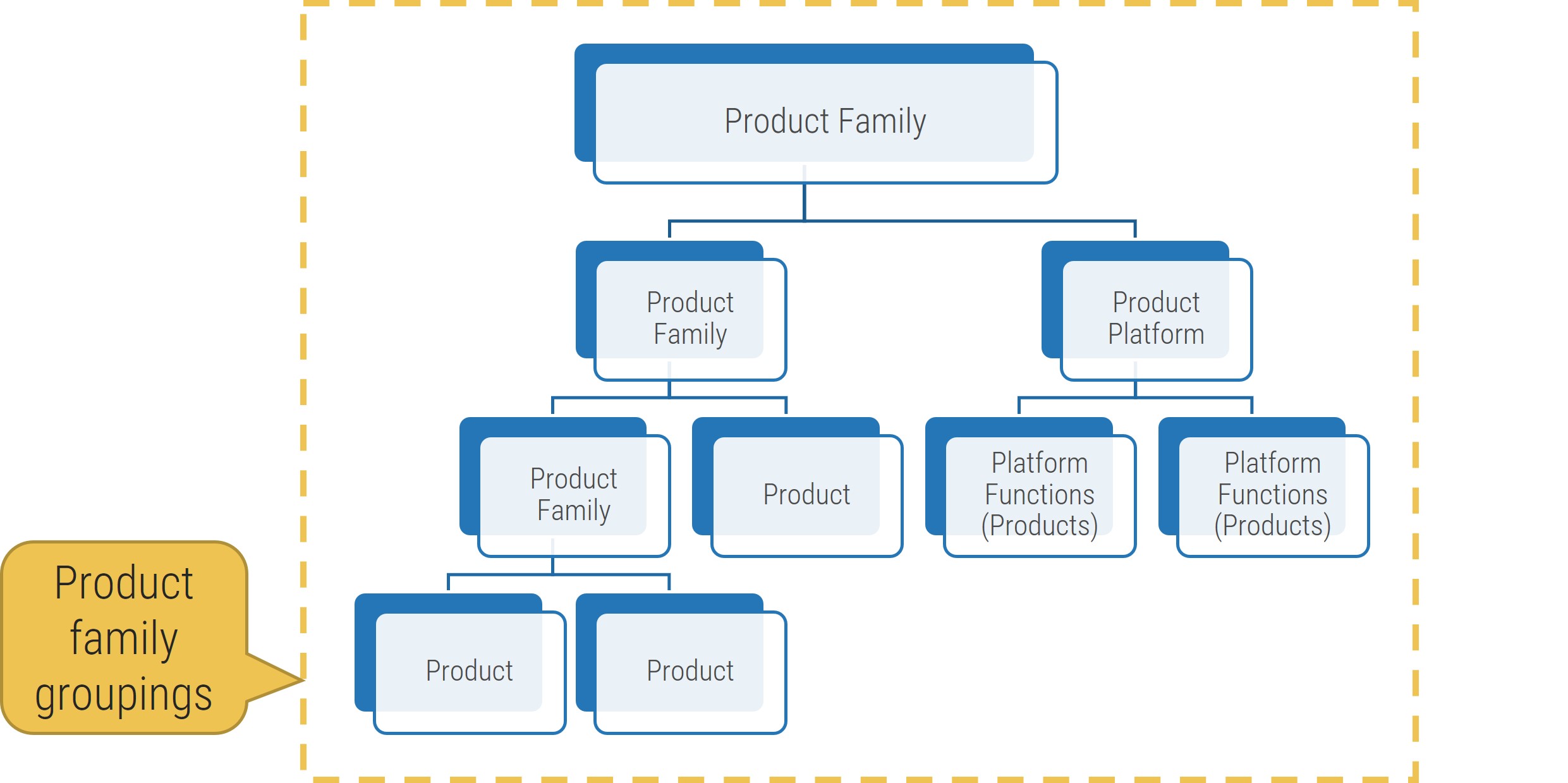

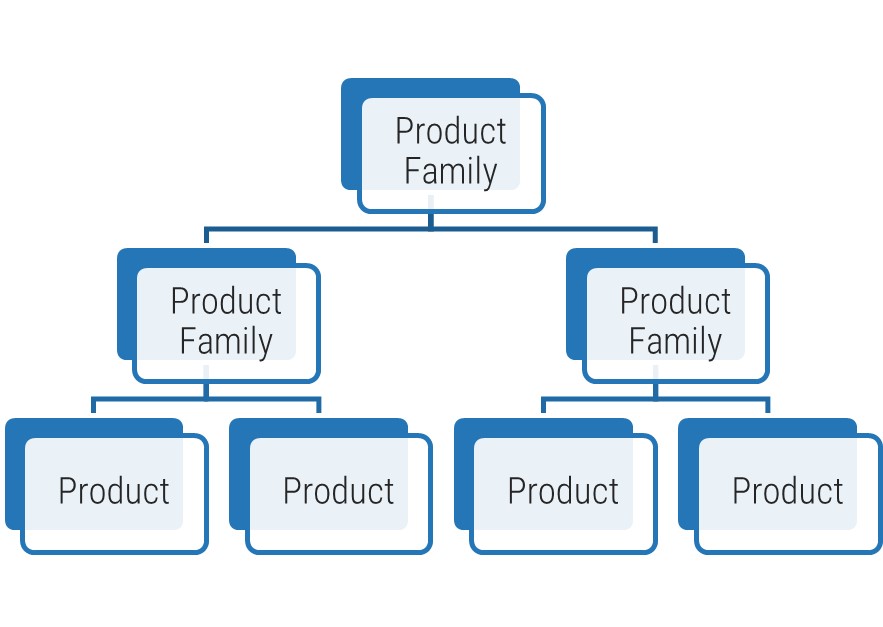

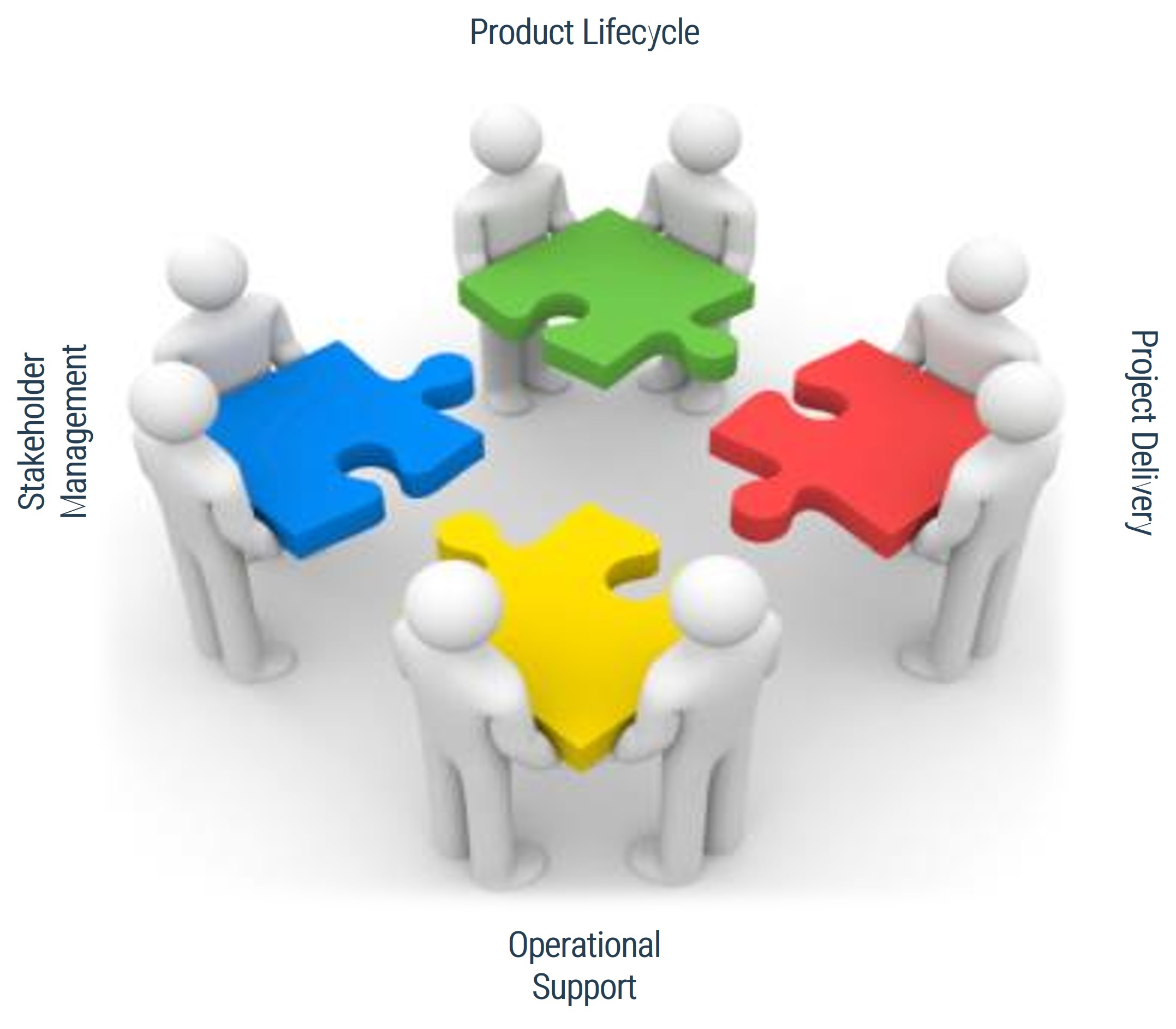

Resource management is one capability within Info-Tech’s larger project portfolio management (PPM) framework.

Resource visibility and capacity awareness permeates the whole of PPM, helping to ensure the right intake decisions get made, and projects are scheduled according to resource and skill availability.

Whether you have an existing PPM strategy that you are looking to optimize or you are just starting on your PPM journey, this blueprint will help you situate your resource management processes within a larger project and portfolio framework.

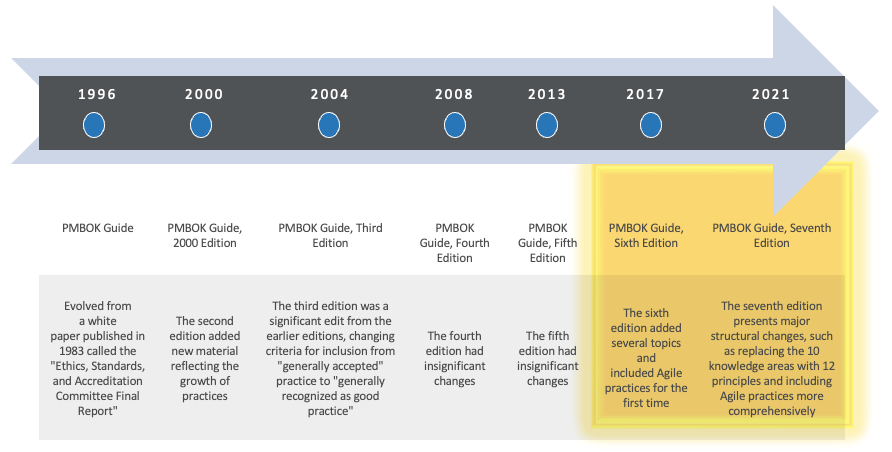

Info-Tech’ s PPM framework is based on extensive research and practical application, and complements industry standards such as those offered by PMI and ISACA.

| Project Portfolio Management

|

| Status & Progress Reporting

|

| Intake, Approval, & Prioritization

|

Resource Management

|

Project Management

|

Project Closure

|

Benefits Tracking

|

| Organizational Change Management

|

| Intake →

|

Execution→

|

Closure

|

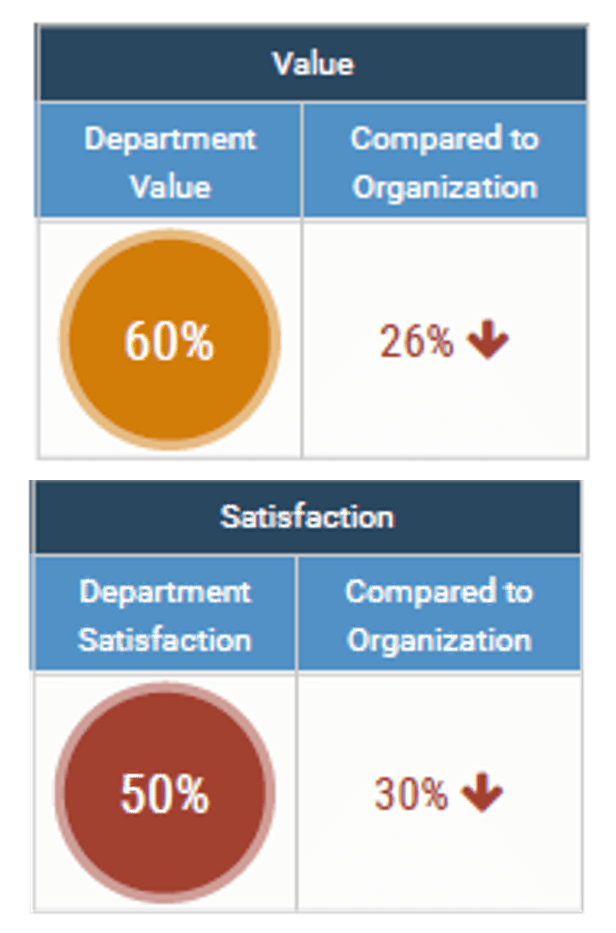

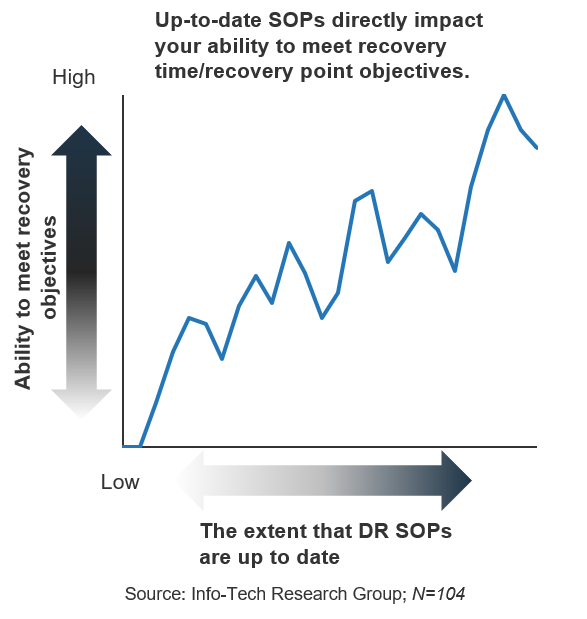

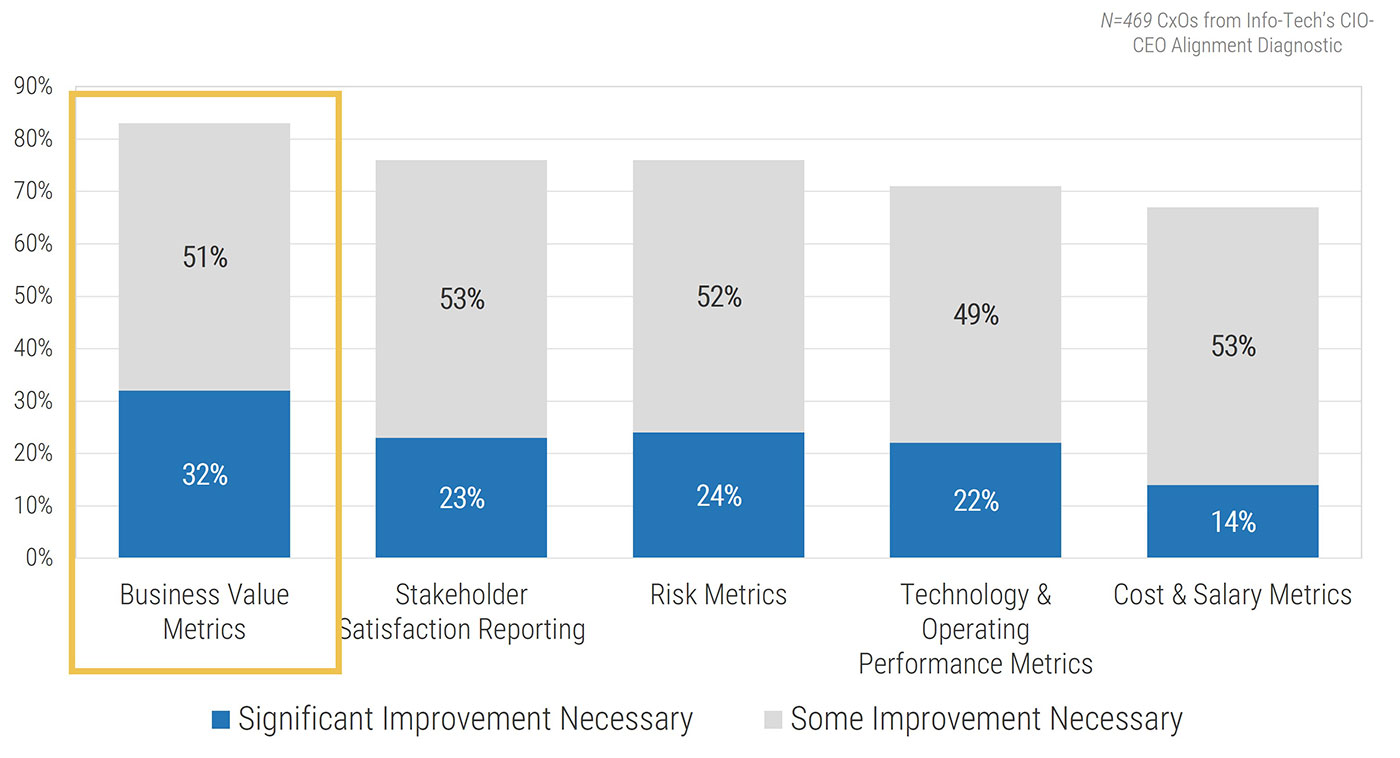

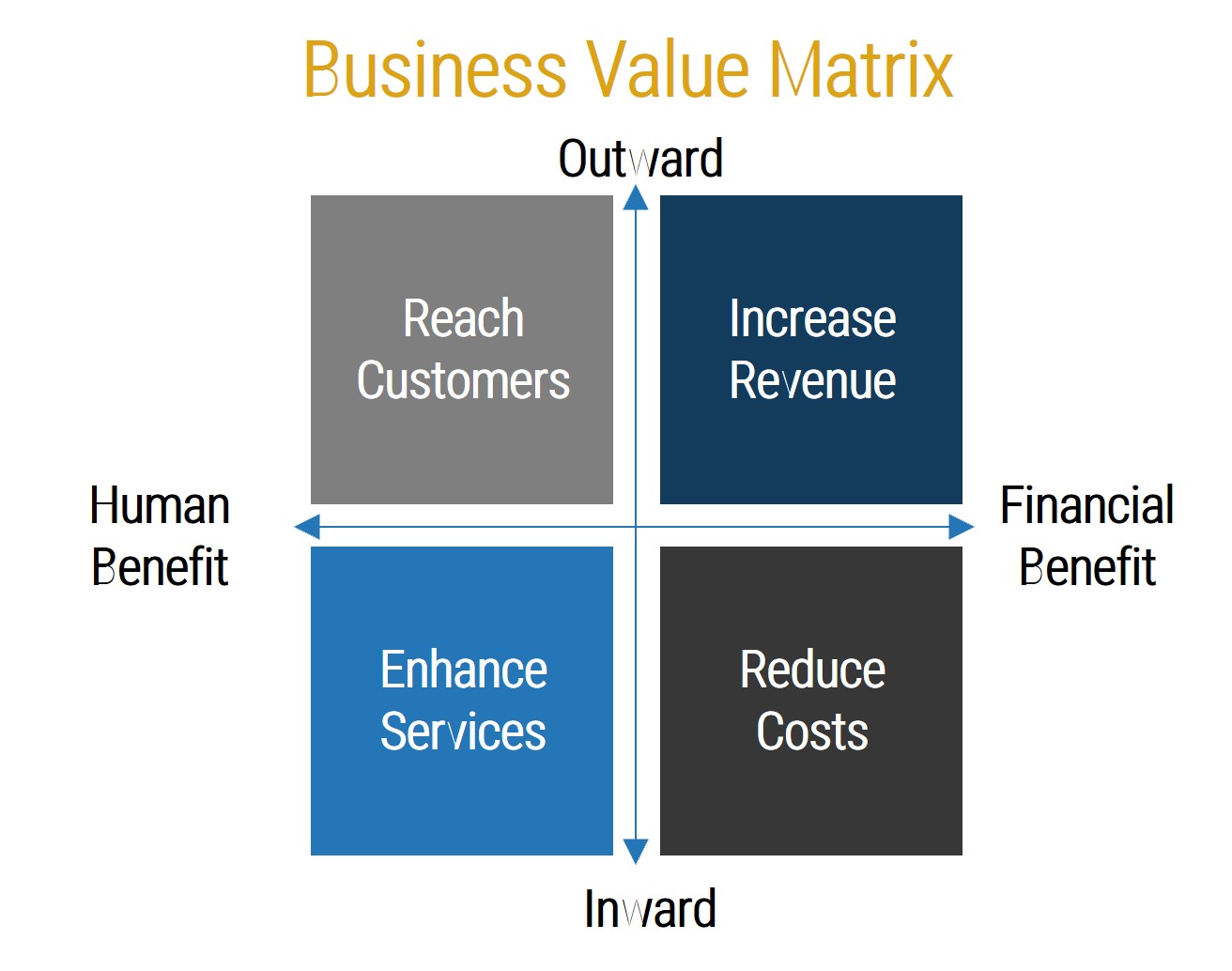

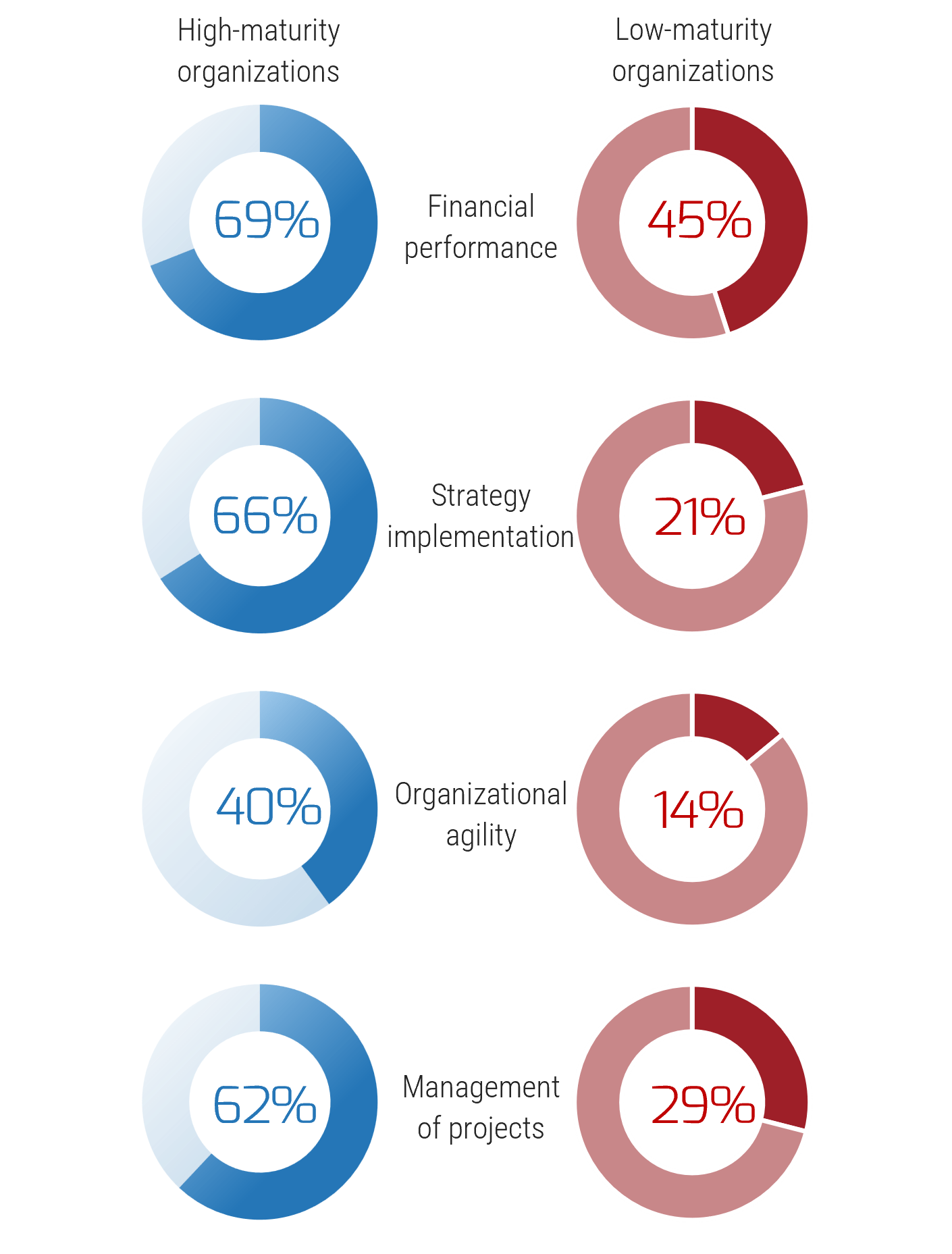

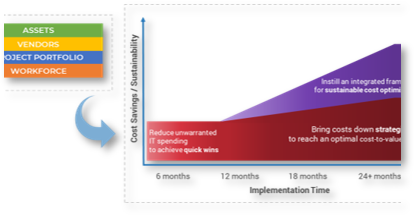

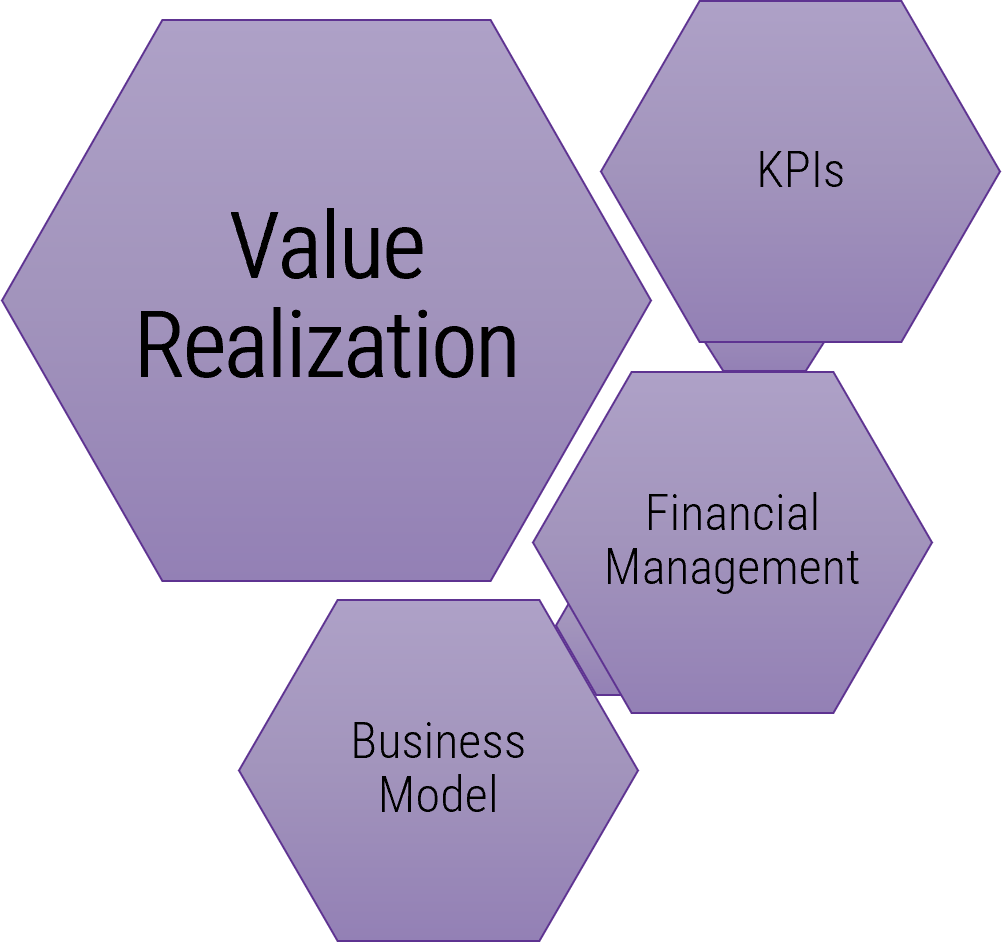

Realize the value that improved resource management practices could bring to your organization

Spend your company’s HR dollars more efficiently.

Improved resource management and capacity awareness will allow your organization to improve resource utilization and increase project throughput.

CIOs, PMOs, and portfolio managers can use this blueprint to improve the alignment between supply and demand. You should be able to gauge the value through the following metrics:

Near-Term Success Metrics (6 to 12 months)

- Increased frequency of currency (i.e. more accurate and usable resource data and reports).

- Improved job satisfaction from project resources due to more even workloads.

- Better ability to schedule project start dates and estimate end dates due to recourse visibility.

Long-Term Success Metrics (12 to 24 months)

- More projects completed on time.

- Reclaimed capacity for project work.

- A reduction in resource waste and increased resource utilization on productive project work.

- Ability to track estimated vs. actual budget and work effort on projects.

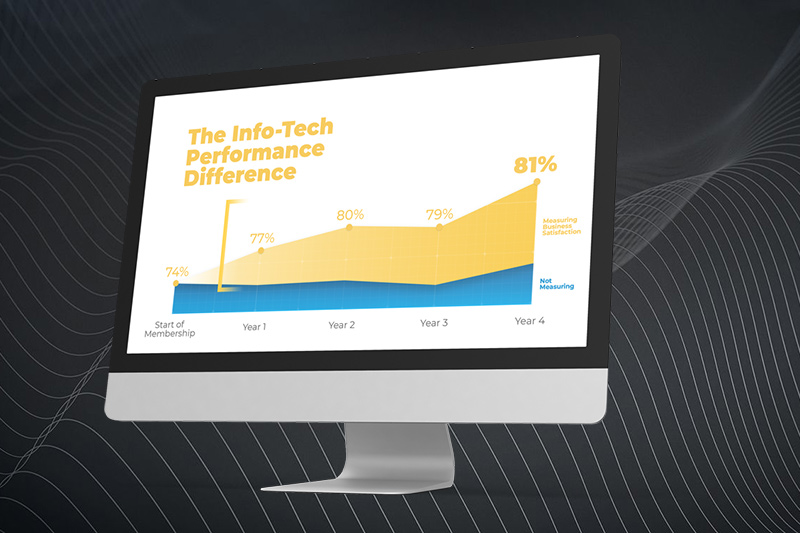

In the past 12 months, Info-Tech clients have reported an average measured value rating of $550,000 from the purchase of workshops based on this research.

Info-Tech client masters resource management by shifting the focus to capacity forecasting

CASE STUDY

Industry Education

Source Info-Tech Client

Situation

- There are more than 200 people in the IT organization.

- IT is essentially a shared services environment with clients spanning multiple institutions across a wide geography.

- The PMO identified dedicated resources for resource management.

Complication

- The definition of “resource management” was constantly shifting between accounting the past (i.e. time records), the present (i.e. work assignments), and the future (i.e. long term project allocations).

- The task data set (i.e. for current work assignments) was not aligned to the historic time records or future capacity.

- It was difficult to predict or account for the spend, which exceeded 30,000 hours per month.

“We’re told we can’t say NO to projects. But this new tool set and approach allows us to give an informed WHEN.” – Senior PMO Director, Education

Resolution

- The leadership decided to forecast and communicate their resource capacity on a 3-4 month forecast horizon using Info-Tech’s Portfolio Manager 2017.

- Unallocated resource capacity was identified within certain skill sets that had previously been assessed as fully allocated. While some of the more high-visibility staff were indeed overallocated, other more junior personnel had been systemically underutilized on projects.

- The high demand for IT project resourcing was immediately placed in the context of a believable, credible expression of supply.

Info-Tech offers various levels of support to best suit your needs

DIY Toolkit

“Our team has already made this critical project a priority, and we have the time and capability, but some guidance along the way would be helpful.”

Guided Implementation

“Our team knows that we need to fix a process, but we need assistance to determine where to focus. Some check-ins along the way would help keep us on track.”

Workshop

“We need to hit the ground running and get this project kicked off immediately. Our team has the ability to take this over once we get a framework and strategy in place.”

Consulting

“Our team does not have the time or the knowledge to take this project on. We need assistance through the entirety of this project.”

Diagnostics and consistent frameworks used throughout all four options

Establish Realistic IT Resource Management Practices – project overview

|

|

1. Take Stock of Organizational Supply and Demand

|

2. Design a Realistic Resource Management Process

|

3. Implement Sustainable Resource Management Practices

|

| Best-Practice Toolkit

|

1.1 Set a resource management course of action

1.2 Create realistic estimates of supply and demand

|

2.1 Customize the seven dimensions of resource management

2.2 Determine the resource management tool that will best support your process

2.3 Build process steps to ensure data accuracy and sustainability

|

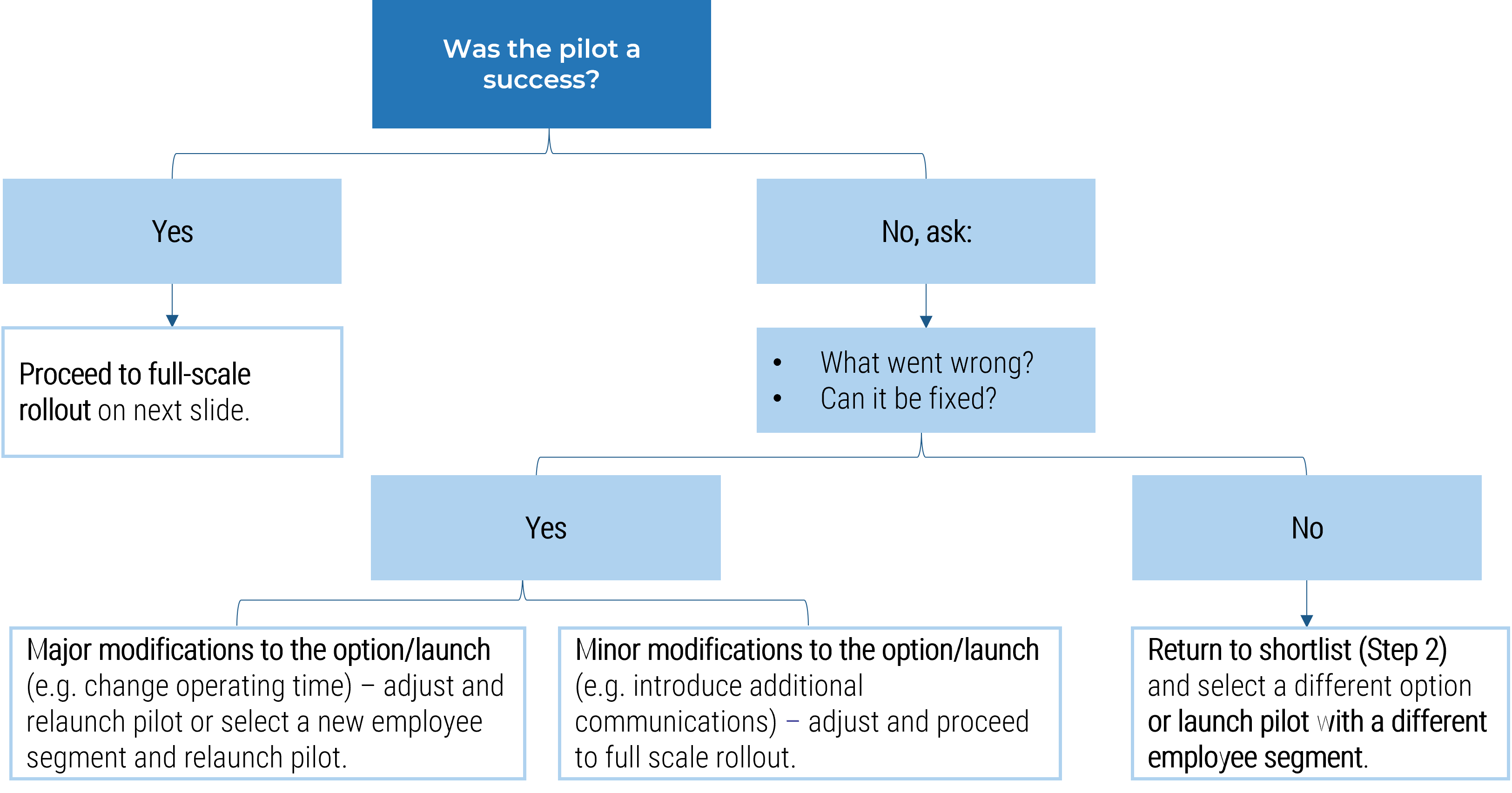

3.1 Pilot your resource management process to assess viability

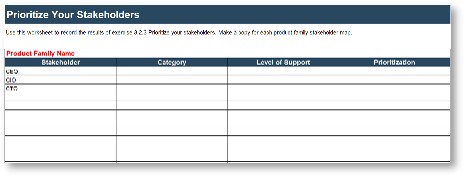

3.2 Plan to engage your stakeholders with your playbook

|

| Guided Implementations

|

- Scoping call

- Assess how accountability for resource management is currently distributed

- Create a realistic estimate of project capacity

- Map all sources of demand on resources at a high level

|

- Set your seven dimensions of resource management

- Jump-start spreadsheet-based resource management with Portfolio Manager Lite

- Build on the workflow to determine how data will be collected and who will support the process

|

- Define the scope of a pilot and determine logistics

- Finalize resource management roles and responsibilities

- Brainstorm and plan for potential resistance to change, objections, and fatigue from stakeholders

|

| Onsite Workshop

|

Module 1:

- Take Stock of Organizational Supply and Demand

|

Module 2:

- Design a Realistic Resource Management Process

|

Module 3:

- Implement Sustainable Resource Management Practices

|

|

|

Phase 1 Outcome:

- Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator

|

Phase 2 Outcome:

- Resource Management Playbook

|

Phase 3 Outcome:

- Resource Management Communications Template

|

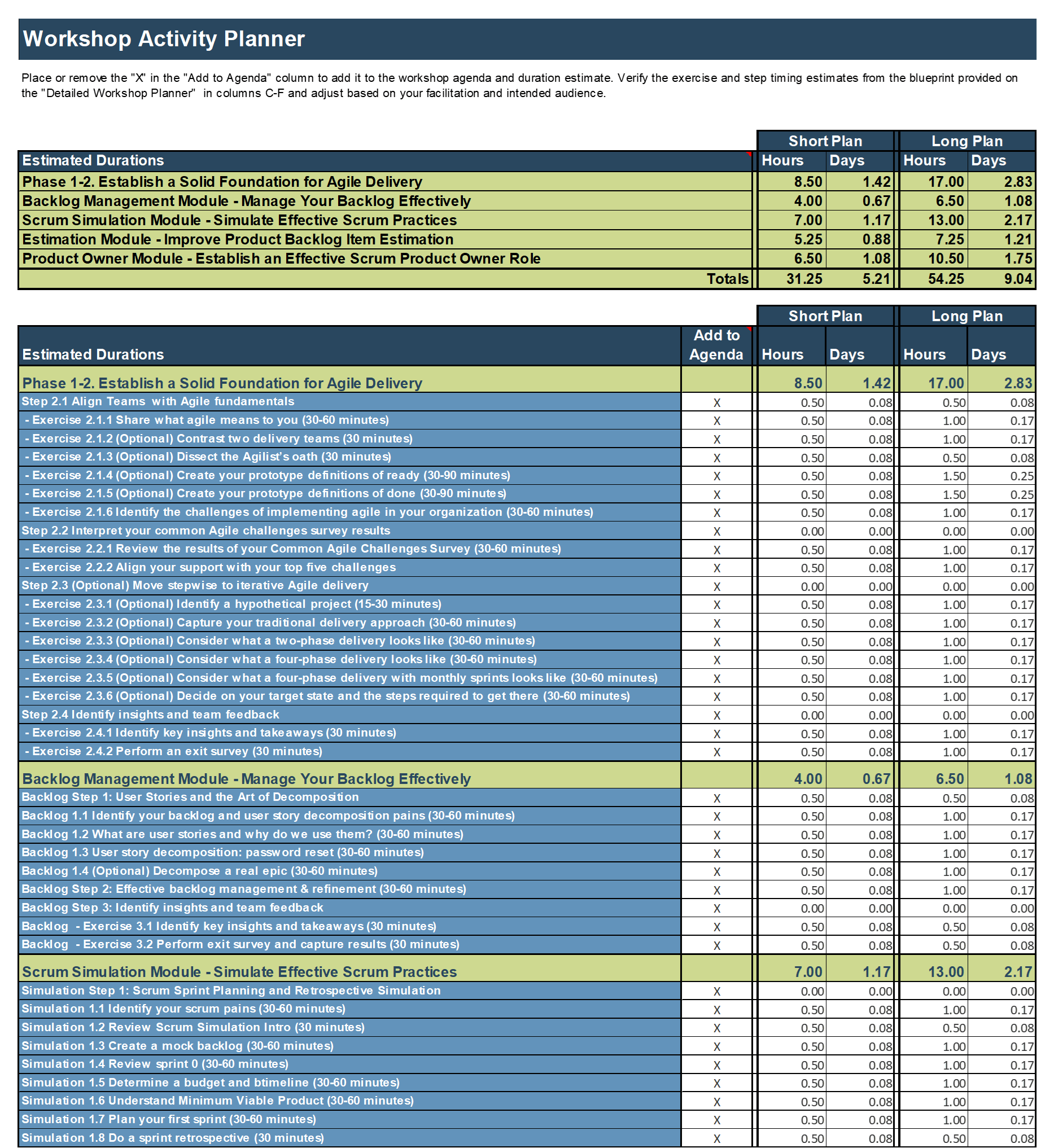

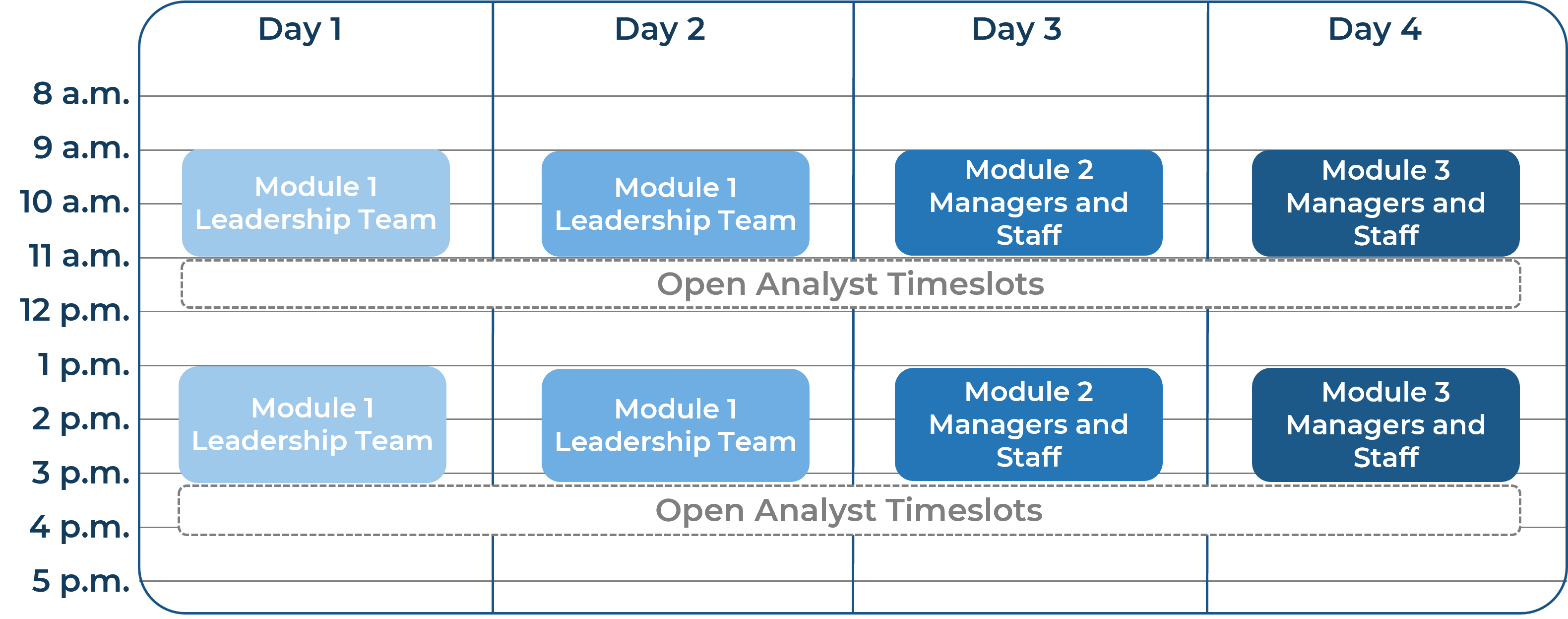

Workshop overview

Contact your account representative or email Workshops@InfoTech.com for more information.

|

|

Workshop Day 1

|

Workshop Day 2

|

Workshop Day 3

|

Workshop Day 4

|

Workshop Day 5

|

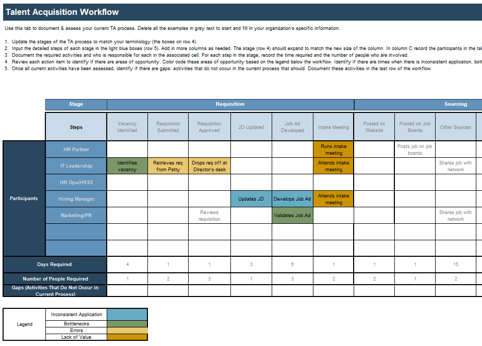

| Activities

|

Introduction to PPM and resource management

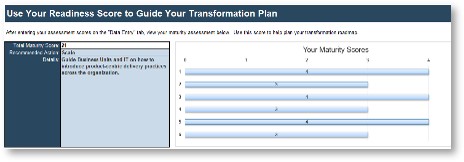

1.1 Complete and review PPM Current State Scorecard Assessment

1.2 Perform root cause analysis of resource management challenges

1.3 Initiate time audit survey of management and staff

|

Take stock of supply and demand

2.1 Review the outputs of the time audit survey and analyze the data

2.2 Analyze project and non-project demands, including the sources of those demands

2.3 Set the seven dimensions of resource management

|

Design a resource management process

3.1 Review resource management tool options

3.2 Prepare a vendor demo script or review Portfolio Manager Lite

3.3 Build process steps to ensure data accuracy and sustainability

|

Pilot and refine the process

4.1 Define methods for piloting the strategy (after the workshop)

4.2 Complete the Process Pilot Plan Template

4.3 Conduct a mock resource management meeting

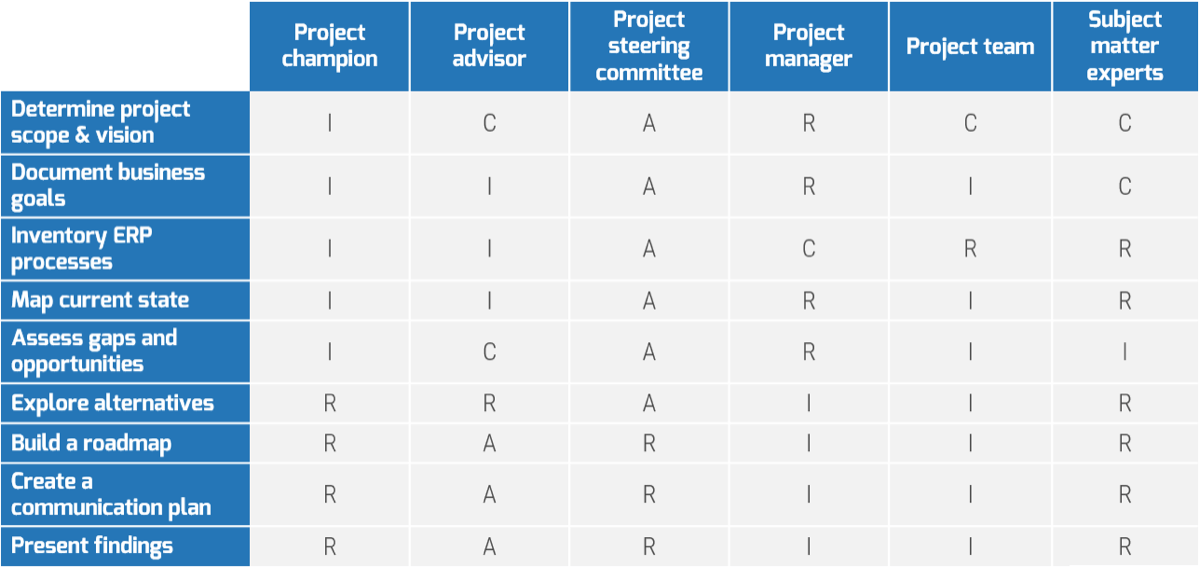

4.4 Perform a RACI exercise

|

Communicate and implement the process

5.1 Brainstorm potential implications of the new strategy and develop a plan to manage stakeholder and staff resistance to the strategy

5.2 Customize the Resource Management Communications Template

5.3 Finalize the playbook

|

| Deliverables

|

- PPM Current State Scorecard Assessment

- Root cause analysis

- Time Audit Workbook and survey templates

|

- Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator

|

- Portfolio Manager Lite

- PPM Solution Vendor Demo Script

- Tentative Resource Management Playbook

|

- Process Pilot Plan Template

- RACI chart

|

- Resource Management Communications Template

- Finalized Resource Management Playbook

|

Phase 1

Take Stock of Organizational Resource Supply and Demand

Phase 1 Outline

Call 1-888-670-8889 or email GuidedImplementations@InfoTech.com for more information.

Complete these steps on your own, or call us to complete a guided implementation. A guided implementation is a series of

2-3 advisory calls that help you execute each phase of a project. They are included in most advisory memberships.

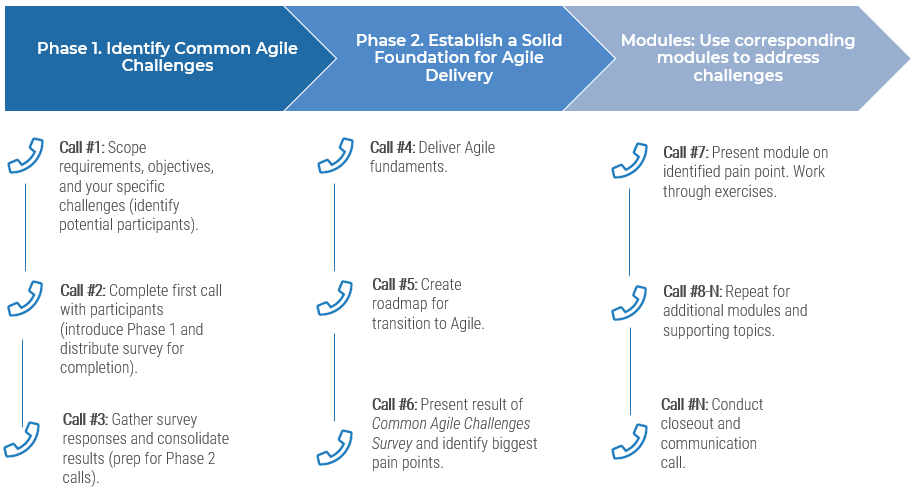

Guided Implementation 1: Take Stock of Organizational Resource Supply and Demand

Proposed Time to Completion (in weeks): 1-2 weeks

Step 1.1: Analyze the current state

Start with an analyst kick-off call:

- Discuss the goals, aims, benefits, and challenges of resource management

- Identify who is currently accountable for balancing resource supply and demand

Then complete these activities…

- Assess the current distribution of accountabilities in resource management

- Delve into your current problems to uncover root causes

- Make a go/no-go decision on developing a new resource management practice

Step 1.2: Estimate your supply and demand

Review findings with analyst:

- Root causes of resource management

- Your current impression about the resource supply-demand imbalance

Then complete these activities…

- Estimate your resource capacity for each role

- Estimate your project/non-project demand on resources

- Validate the findings with a time-tracking survey

With these tools & templates:

- Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator

- Time-Tracking Survey Email Template

Phase 1 Results & Insights:

A matrix organization creates many small, untraceable demands that are often overlooked in resource management efforts, which leads to underestimating total demand and overcommitting resources. To capture them and enhance the success of your resource management effort, focus on completeness rather than precision. Precision of data will improve over time as your process maturity grows.

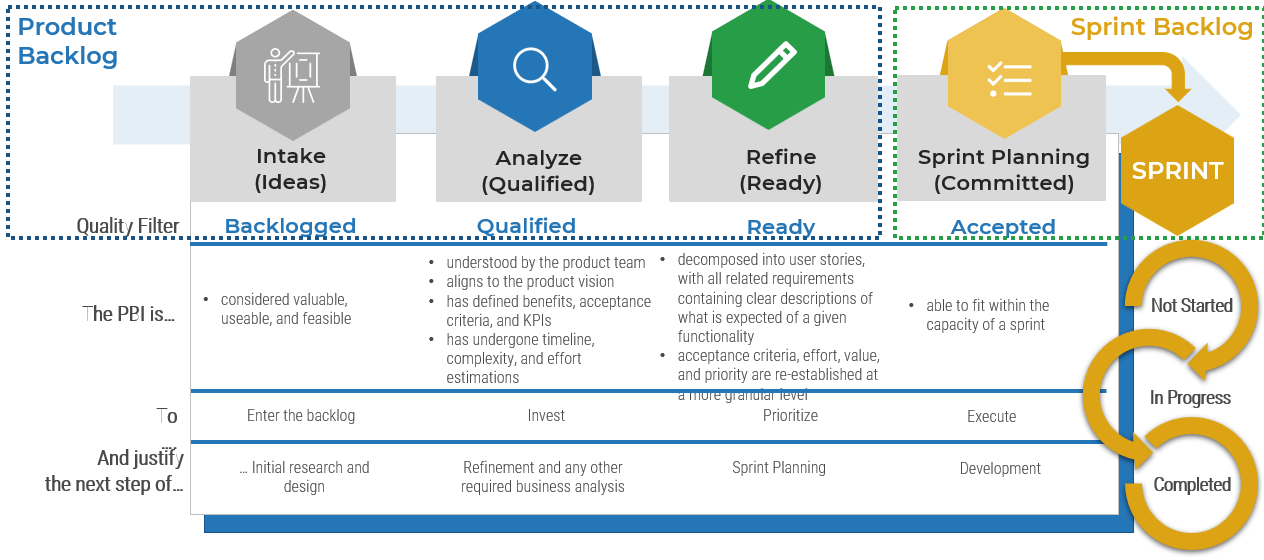

Step 1.1: Set a resource management course of action

PHASE 1

1.1 Set a course of action

1.2 Estimate supply and demand

PHASE 2

2.1 Select resource management dimensions

2.2 Select resource management tools

2.3 Build process steps

PHASE 3

3.1 Pilot your process for viability

3.2 Plan stakeholder engagement

This step will walk you through the following activities:

- Determine your resource management process capability level

- Assess how accountability for resource management is currently distributed

This step involves the following participants:

- CIO / IT Director

- PMO Director/ Portfolio Manager

- Functional / Resource Managers

- Project Managers

Outcomes of this step

- Current distribution of accountability for resource management practice

- Root-cause analysis of resourcing challenges facing the organization

- Commitment to implementing a right-sized resource management practice

“Too many projects, not enough resources” is the reality of most IT environments

A profound imbalance between demand (i.e. approved project work and service delivery commitments) and supply (i.e. people’s time) is the top challenge IT departments face today..

In today’s organizations, the desires of business units for new products and enhancements, and the appetites of senior leadership to approve more and more projects for those products and services, far outstrip IT’s ability to realistically deliver on everything.

The vast majority of IT departments lack the resourcing to meet project demand – especially given the fact that day-to-day operational demands frequently trump project work.

As a result, project throughput suffers – and with it, IT’s reputation within the organization.

Info-Tech Insight

Where does the time go? The portfolio manager (or equivalent) should function as the accounting department for time, showing what’s available in IT’s human resources budget for projects and providing ongoing visibility into how that budget of time is being spent.

Resource management can help to even out staff workloads and improve project and service delivery results

As the results of a recent survey* show, the top three pain points for IT and PMO leaders all revolve around a wider cultural negligence concerning staff time:

- Overcommitted resources

- Constant change that affects staff assignments

- An inability to prioritize shared resources

A resource management strategy can help to alleviate these pain points and reconcile the imbalance between supply and demand by achieving the following outcomes:

- Improving resource visibility

- Reducing overallocation, and accordingly, resource stress

- Reducing project delay

- Improving resource efficiency and productivity

Top risks associated with poor resource management

Inability to complete projects on time – 52%

Inability to innovate fast enough – 39%

Increased project costs – 38%

Missed business opportunities – 34%

Dissatisfied customers or clients – 32%

12 times more waste – Organizations with poor resource management practices waste nearly 12 times more resource hours than high-performing organizations. (PMI, 2014)

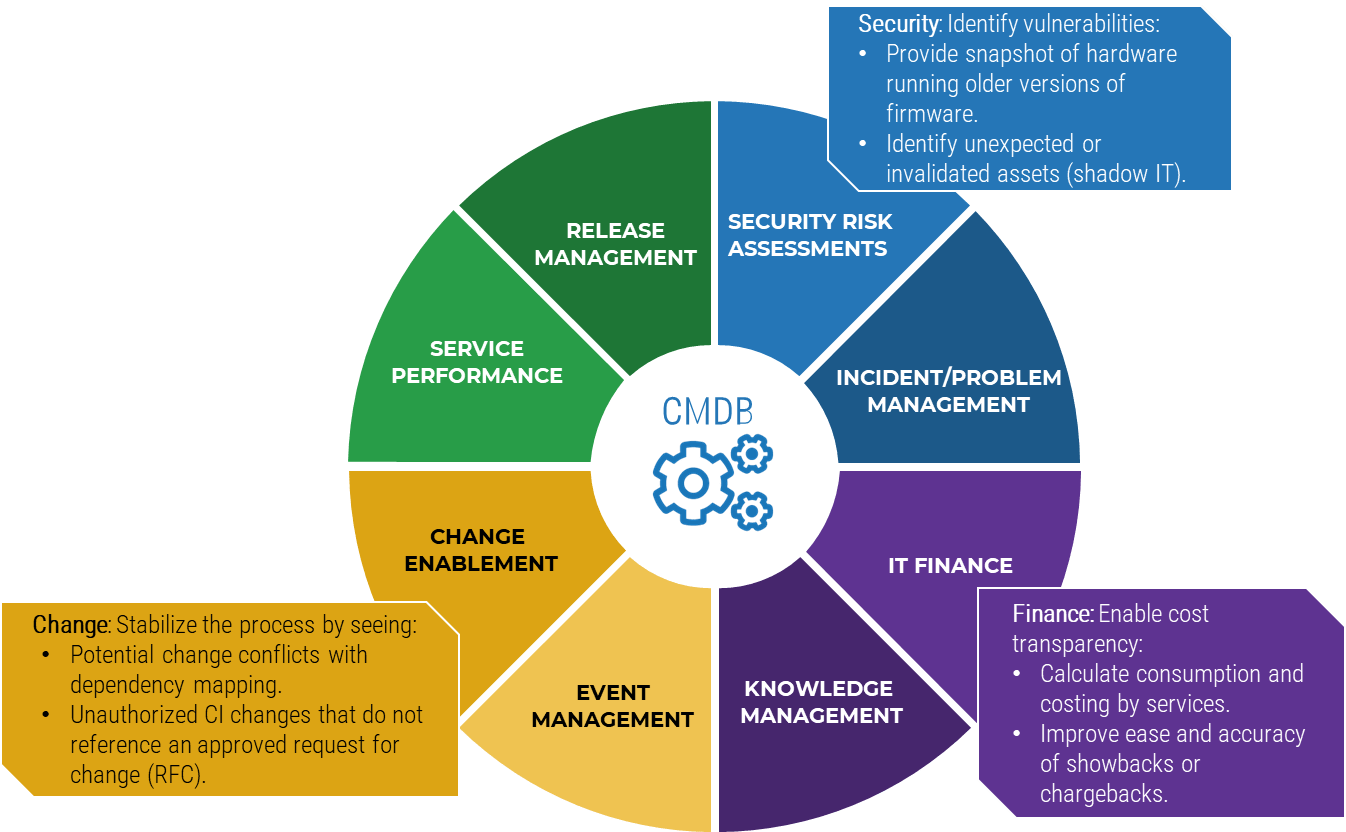

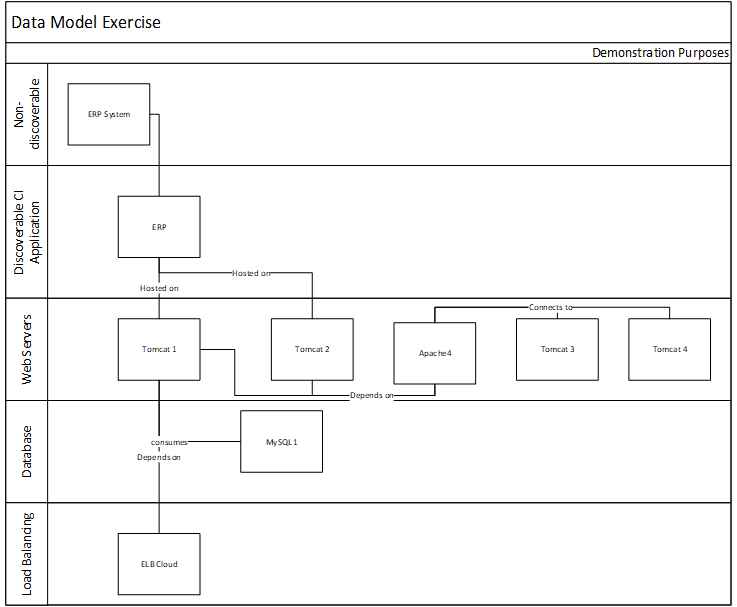

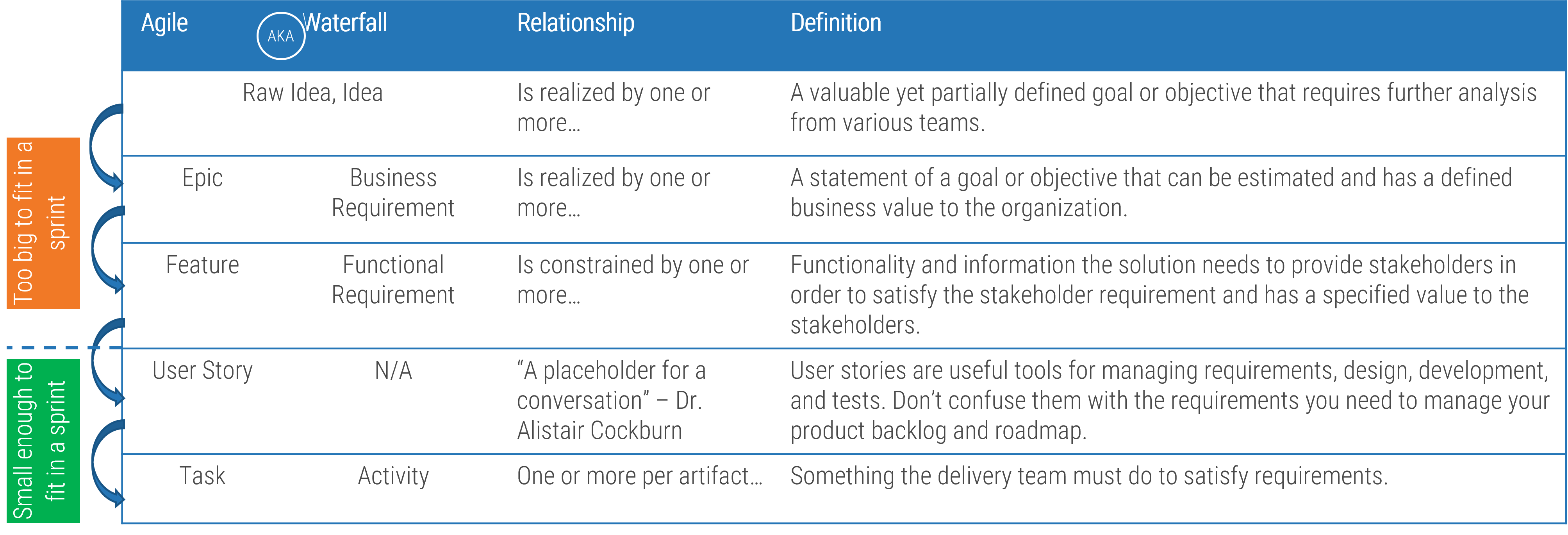

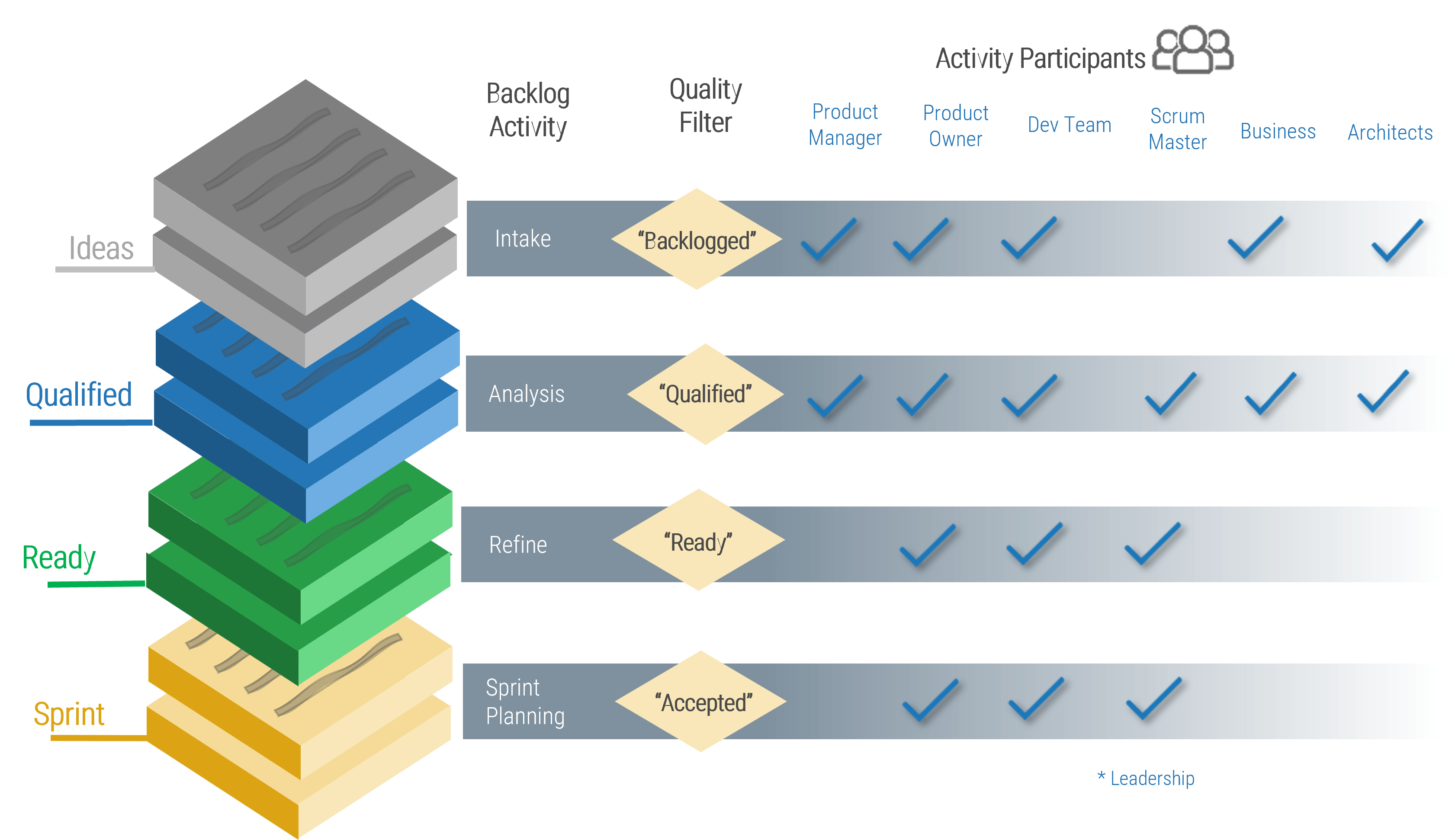

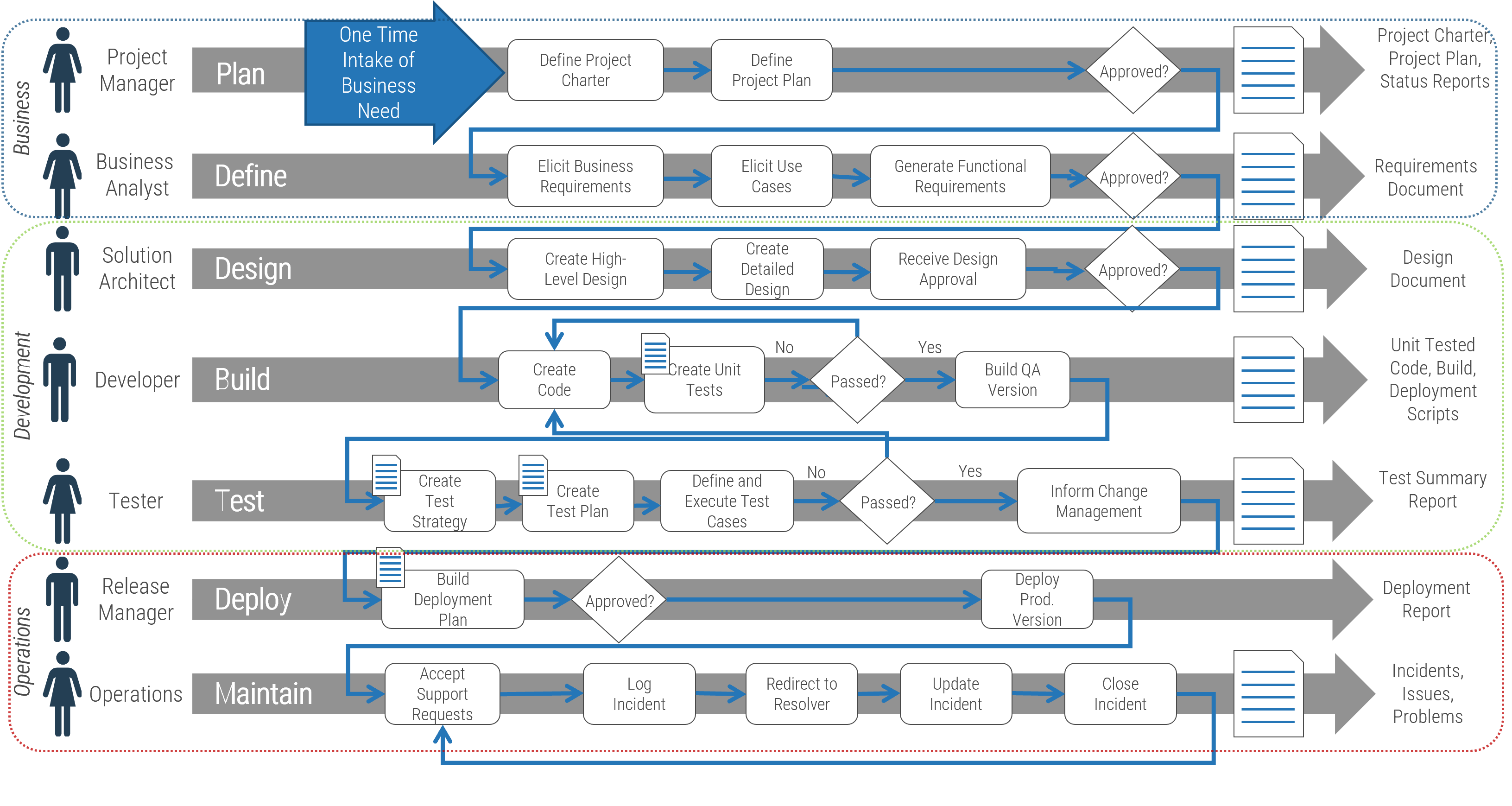

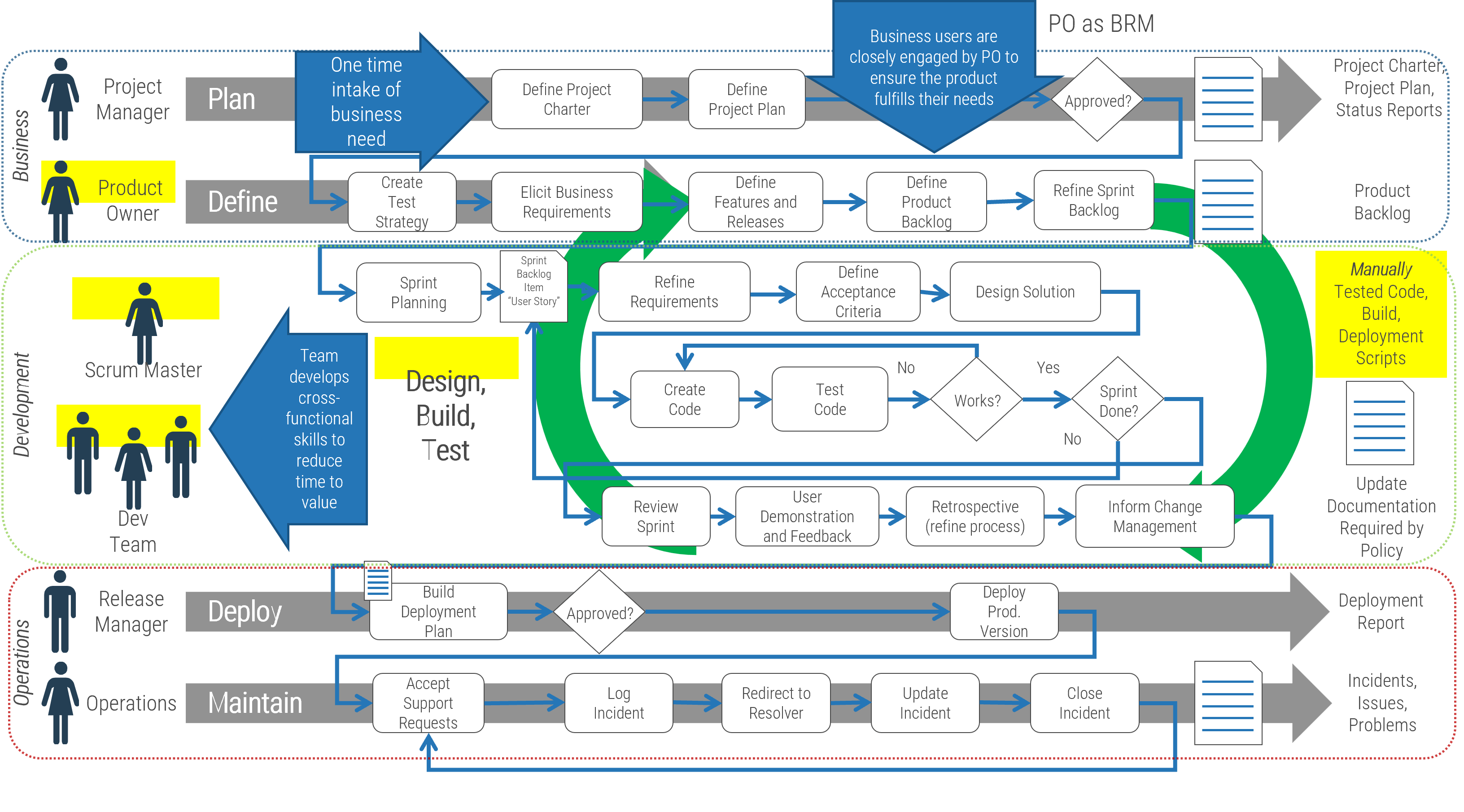

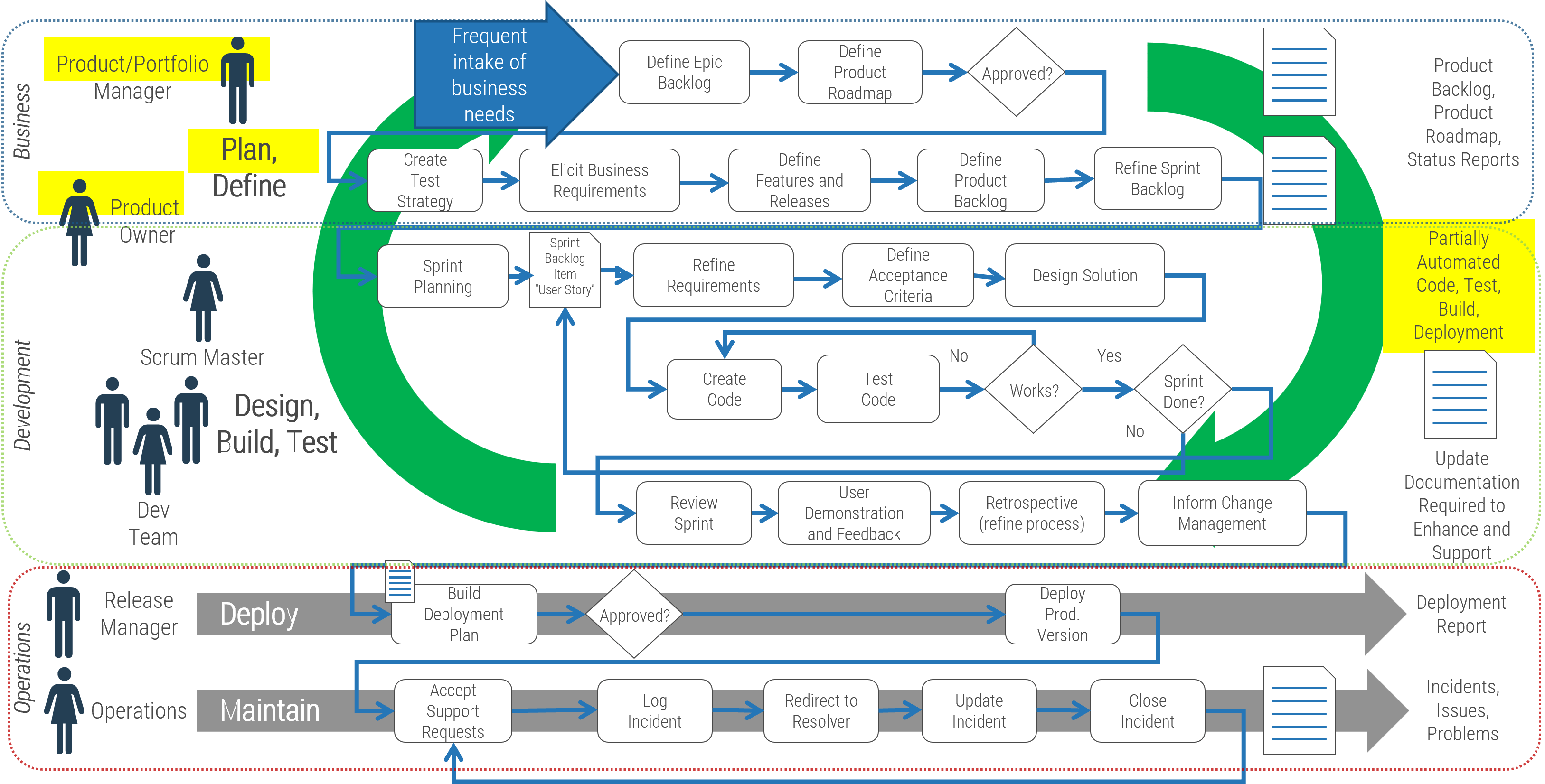

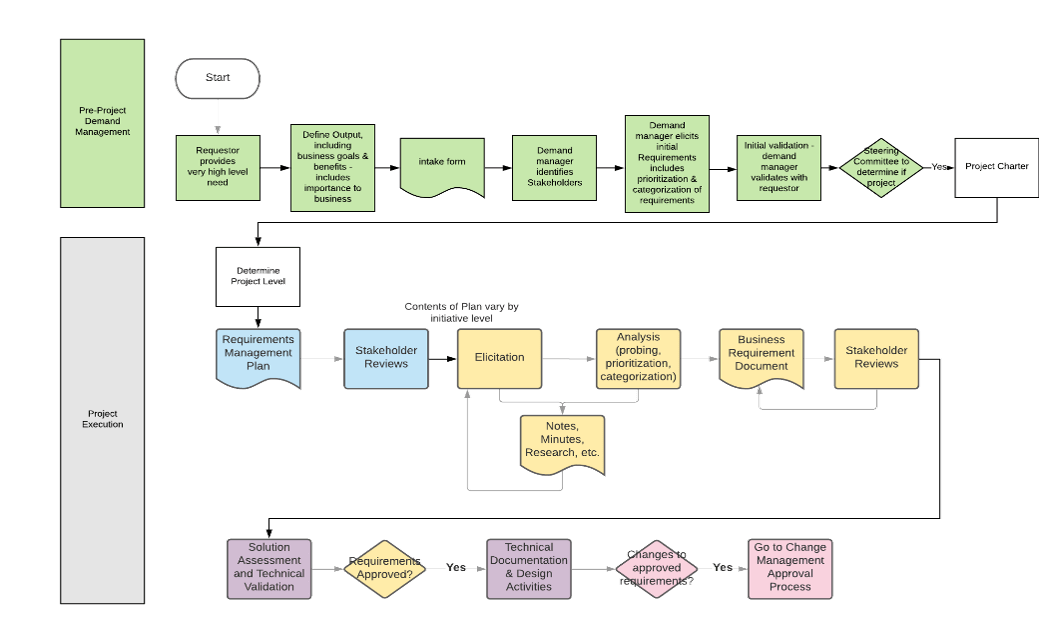

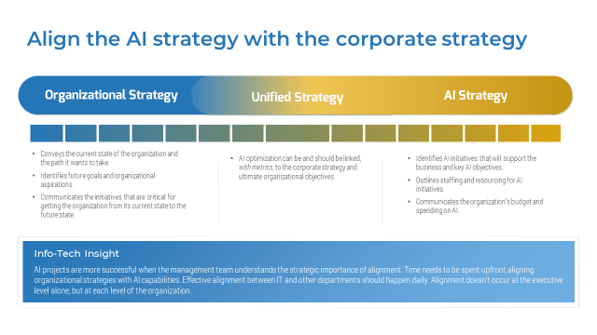

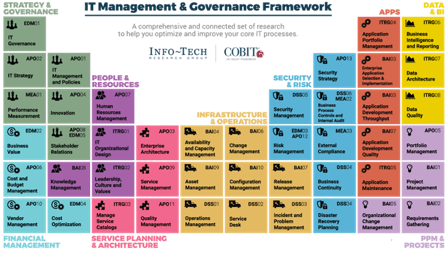

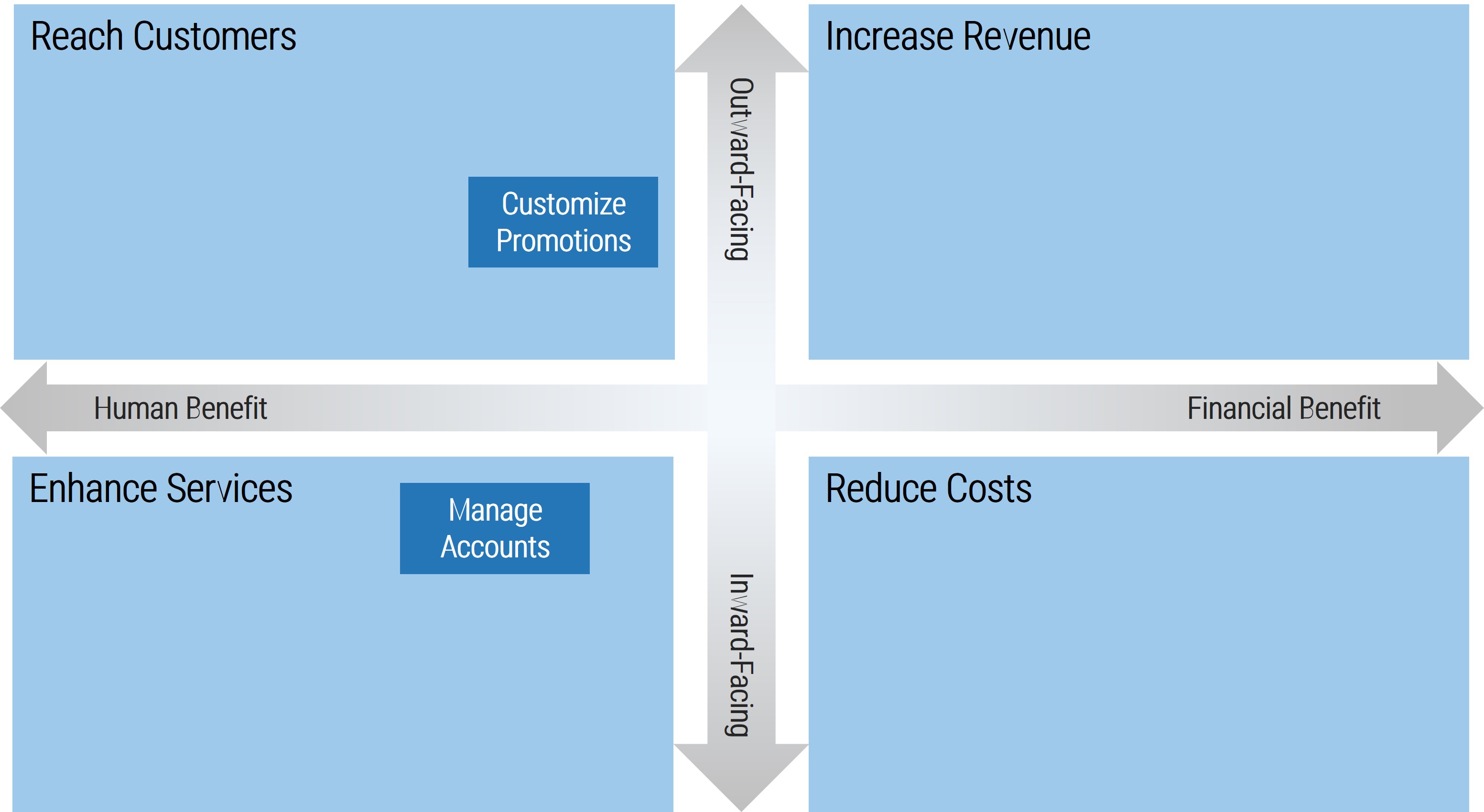

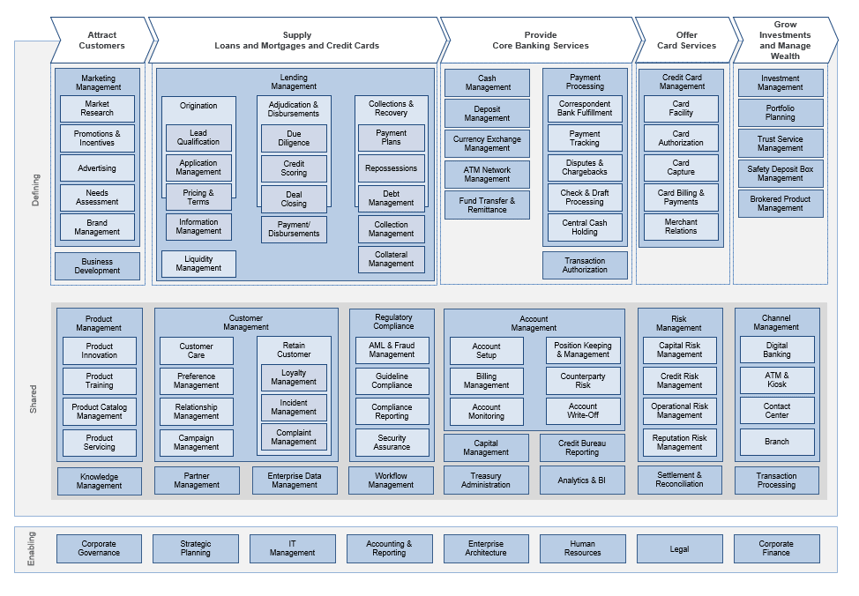

Resource management is a core process in Info-Tech’s project portfolio management framework

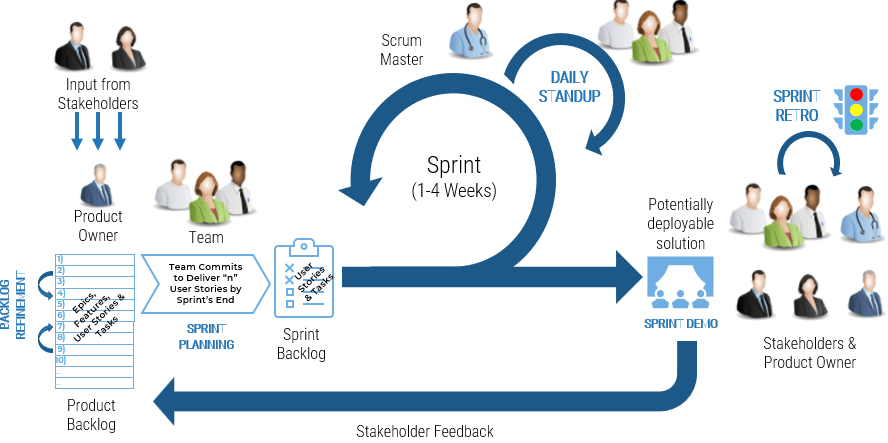

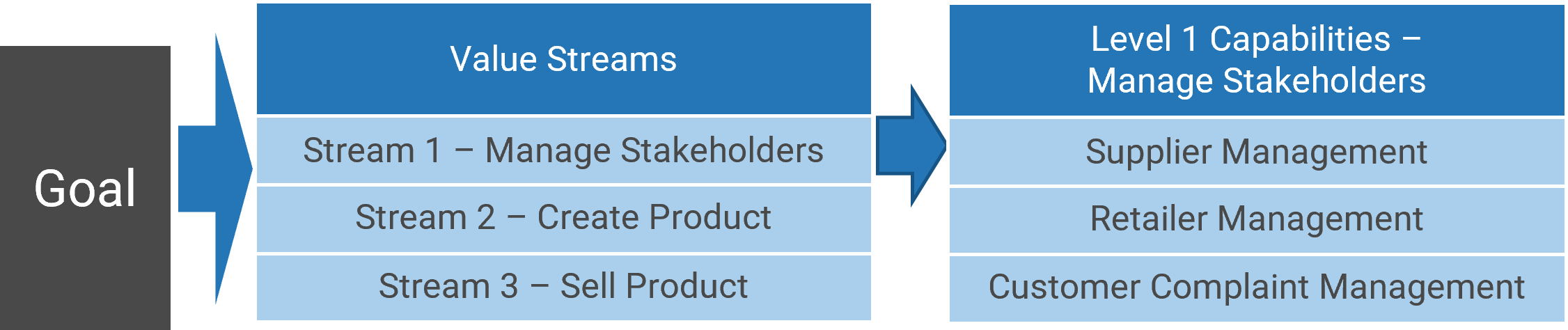

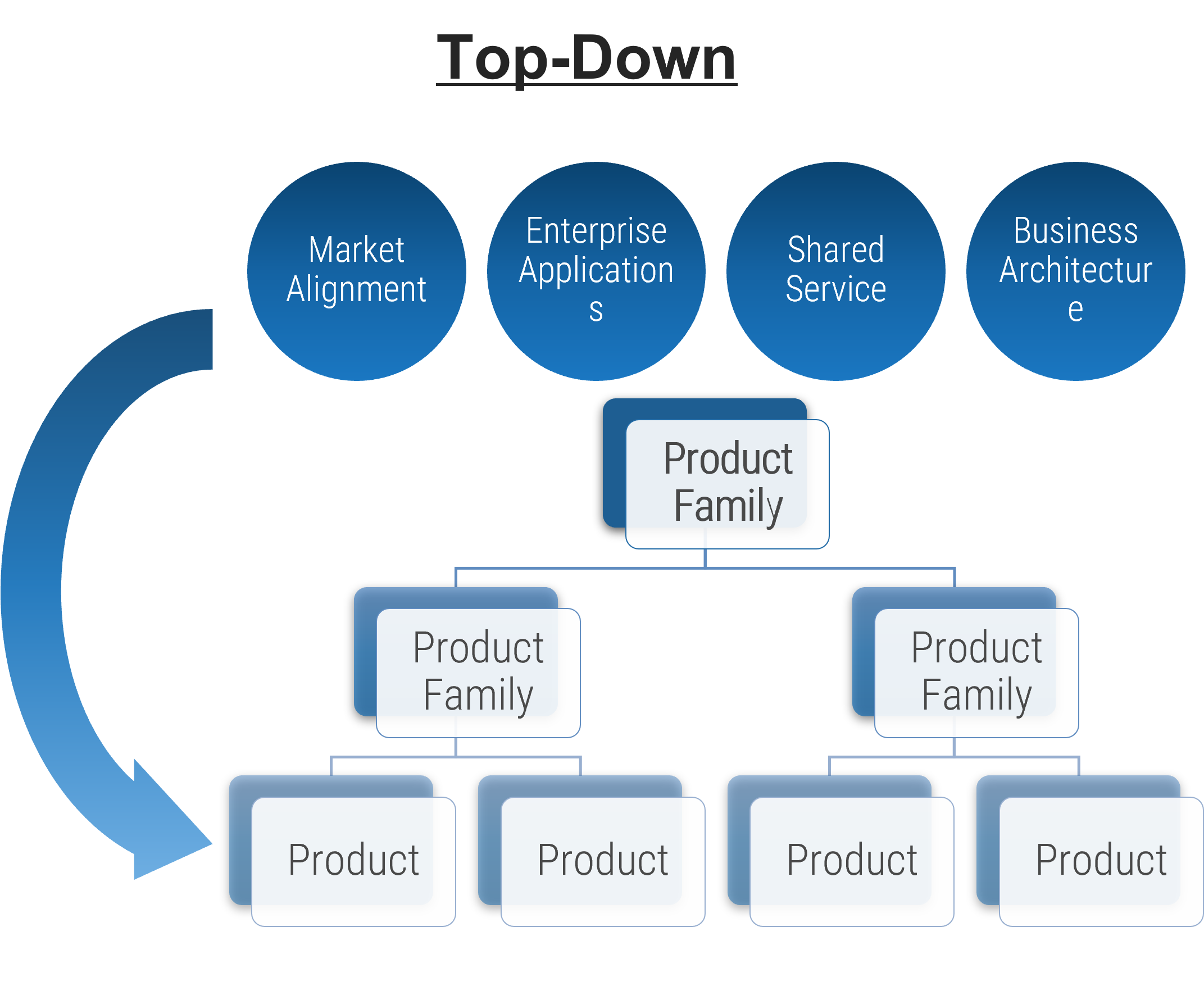

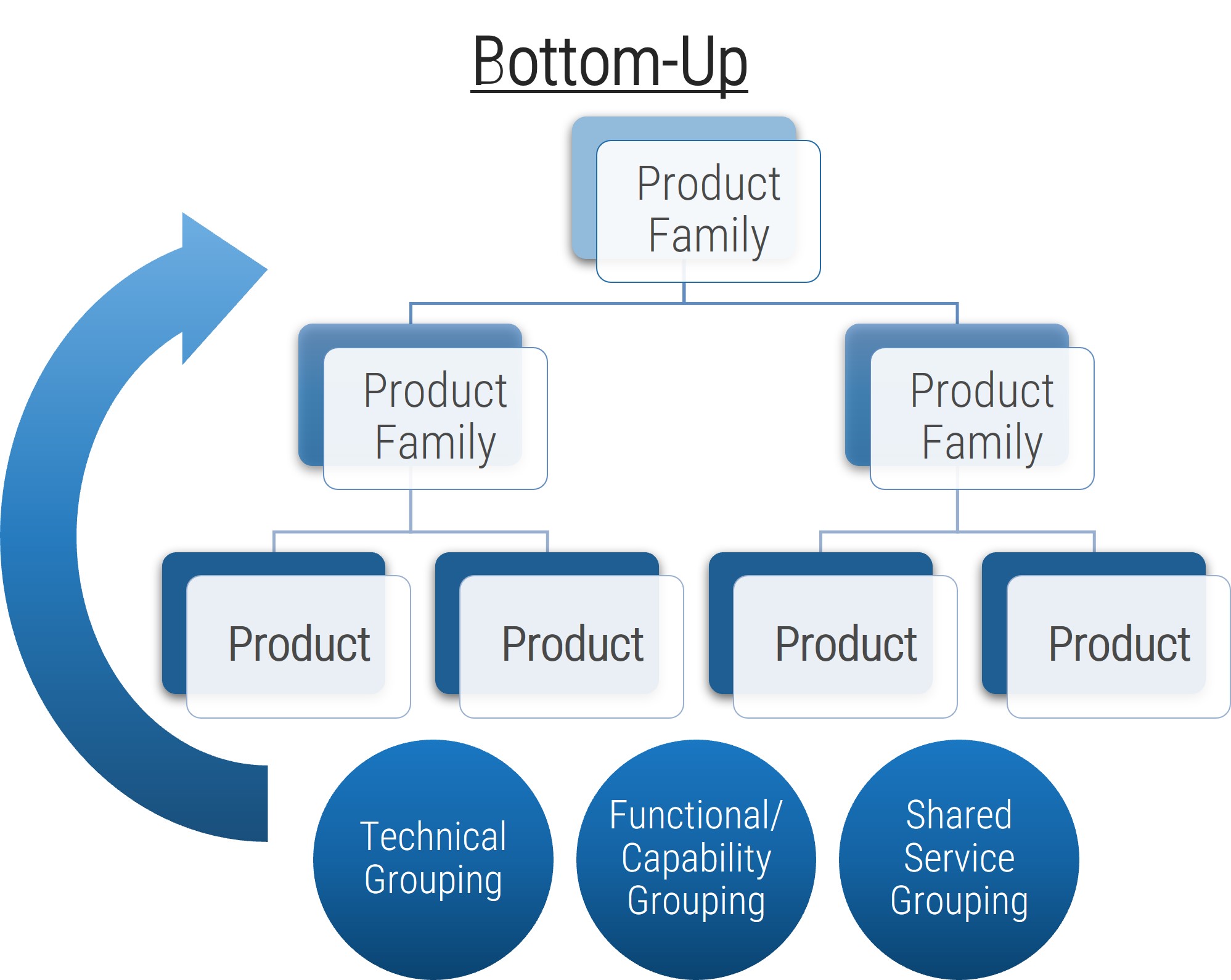

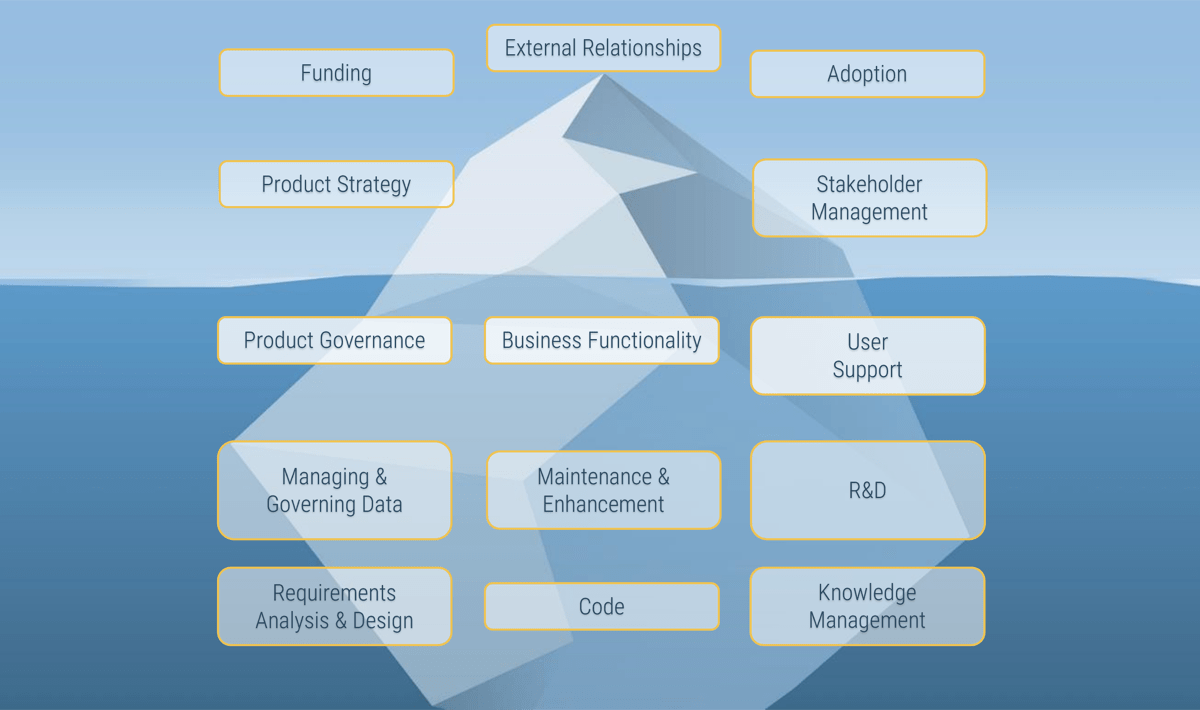

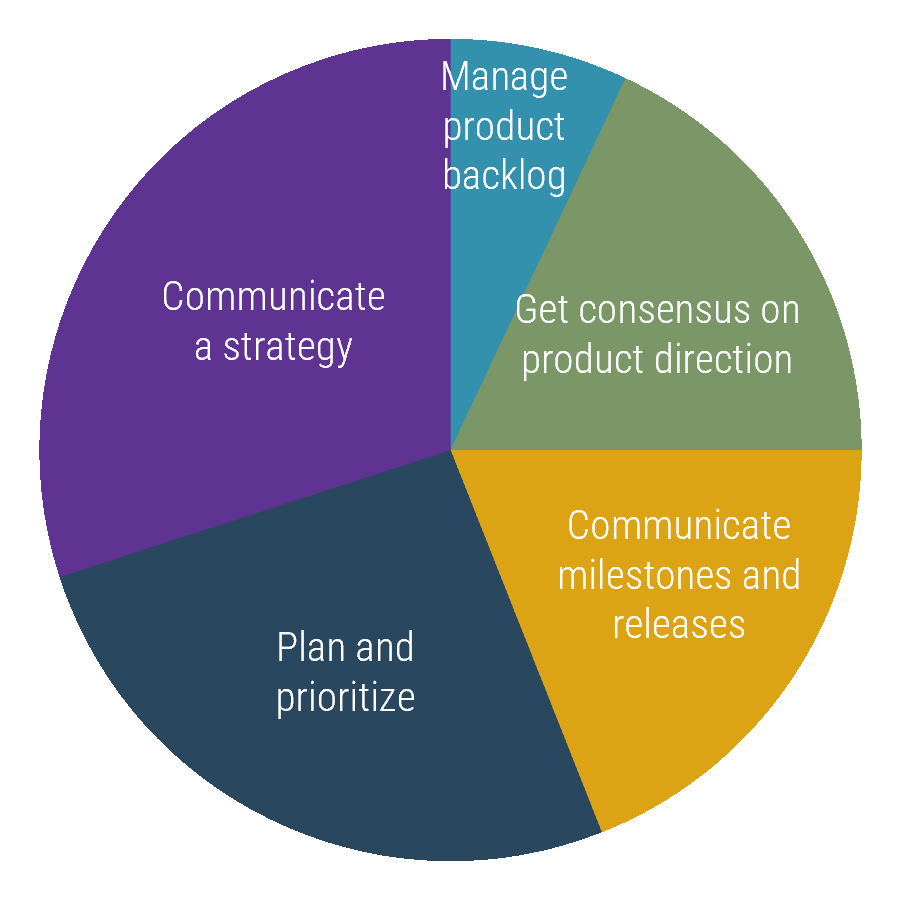

Project portfolio management (PPM) creates a stable and secure infrastructure around projects.

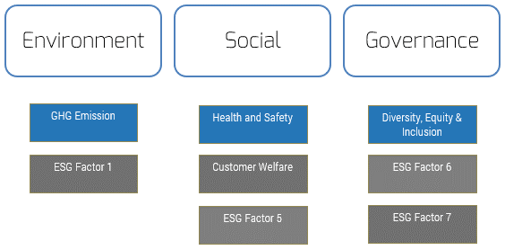

PPM’s goal is to maximize the throughput of projects that provide strategic and operational value to the organization. To do this, a PPM strategy must help to:

| Info-Tech's Project Portfolio Management Process Model

|

| 3. Status & Progress Reporting [make sure the projects are okay]

|

| 1. Intake, Approval, & Prioritization [select the right projects]

|

2. Resource Management [Pick the right time and people to execute the projects

|

Project Management

|

4. Project Closure

[make sure the projects get done]

|

5. Benefits Tracking

[make sure they were worth doing]

|

| Organizational Change Management

|

| Intake →

|

Execution→

|

Closure

|

If you don’t yet have a PPM strategy in place, or would like to revisit your existing PPM strategy before implementing resource management practices, see Info-Tech’s blueprint, Develop a Project Portfolio Management Strategy.

Effective resource management is rooted in a relatively simple set of questions

However, while the questions are rather simple, the answers become complicated by challenges unique to matrix organizations and other workplace realities in 2017.

To support the goals of PPM more generally, resource management must (1) supply quality work-hours to approved and ongoing projects, and (2) supply reliable data with which to steer the project portfolio.

To do this, a resource management strategy must address a relatively straightforward set of questions.

Key Questions

- Who assigns the resources?

- Who feeds the data on resources?

- How do we make sure it’s valid?

- How do we handle contingencies when projects are late or when availability changes?

Challenges

- Matrix organizations require project workers to answer to many masters and balance project work with “keep the lights on” activities and other administrative work.

- Interruptions, distractions, and divided attention create consistent challenges for workplace productivity.

"In matrix organizations, complicated processes and tools get implemented to answer the deceptively simple question “what’s Bob going to work on over the next few months?” Inevitably, the data captured becomes the focus of scrutiny as functional and project managers complain about data inaccuracy while simultaneously remaining reluctant to invest the effort necessary to improve quality." – Kiron Bondale

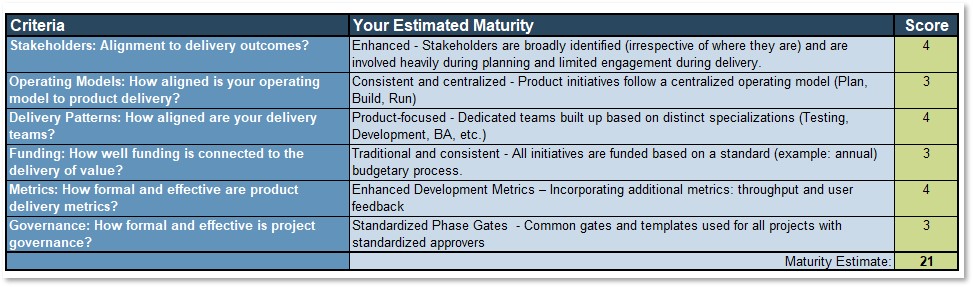

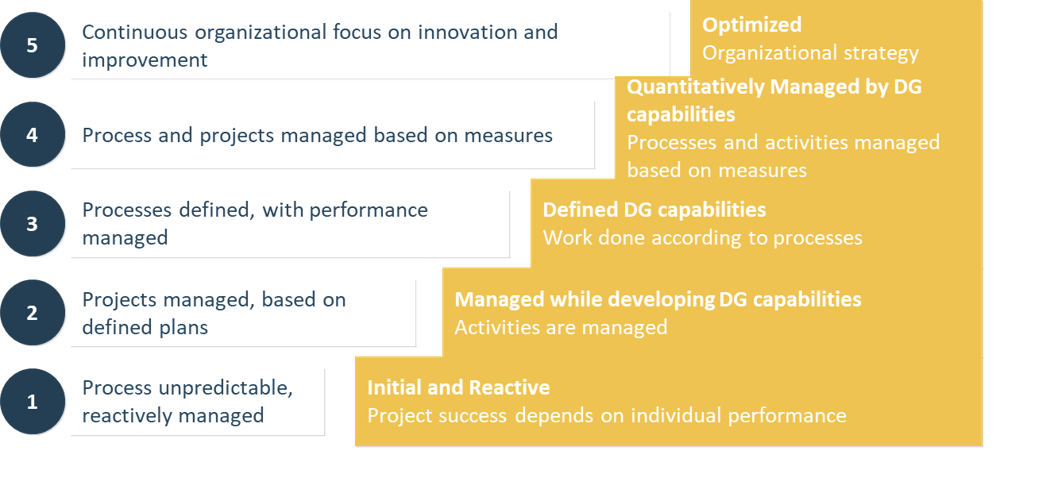

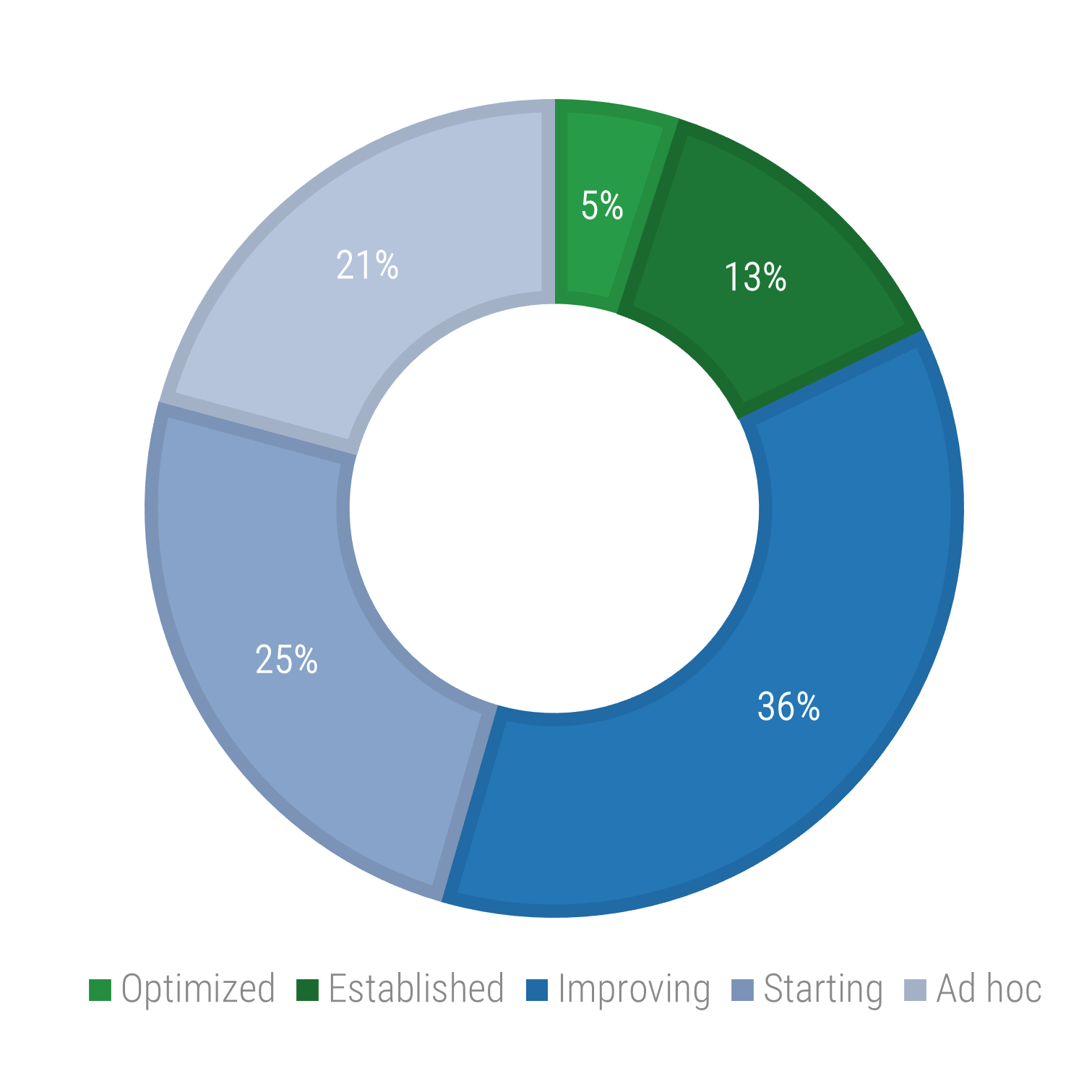

Determine your organization’s resource management capability level with a maturity assessment

1.1.1

10 minutes

Input

- Organizational strategy and culture

Output

- Resource management capability level

Materials

Participants

- PMO Director/ Portfolio Manager

- Project Managers

- Resource Managers

Kick-off the discussion on the resource management process by deciding which capability level most accurately describes your organization’s current state.

|

|

Capability Level Descriptions

|

| Capability Level 5: Optimized

|

Our organization has an accurate picture of project versus non-project workloads and allocates resources accordingly. We periodically reclaim lost capacity through organizational and behavioral change.

|

| Capability Level 4: Aligned

|

We have an accurate picture of how much time is spent on project versus non-project work. We allocate resources to these projects accordingly. We are checking in on project progress bi-weekly.

|

| Capability Level 3: Pixelated

|

We are allocating resources to projects and tracking progress monthly. We have a rough estimate of how much time is spent on project versus non-project work.

|

| Capability Level 2: Opaque

|

We match resource teams to projects and check in annually, but we do not forecast future resource needs or track project versus non-project work.

|

| Capability Level 1: Unmanaged

|

Our organization expects projects to be finished, but there is no process in place for allocating resources or tracking project progress.

|

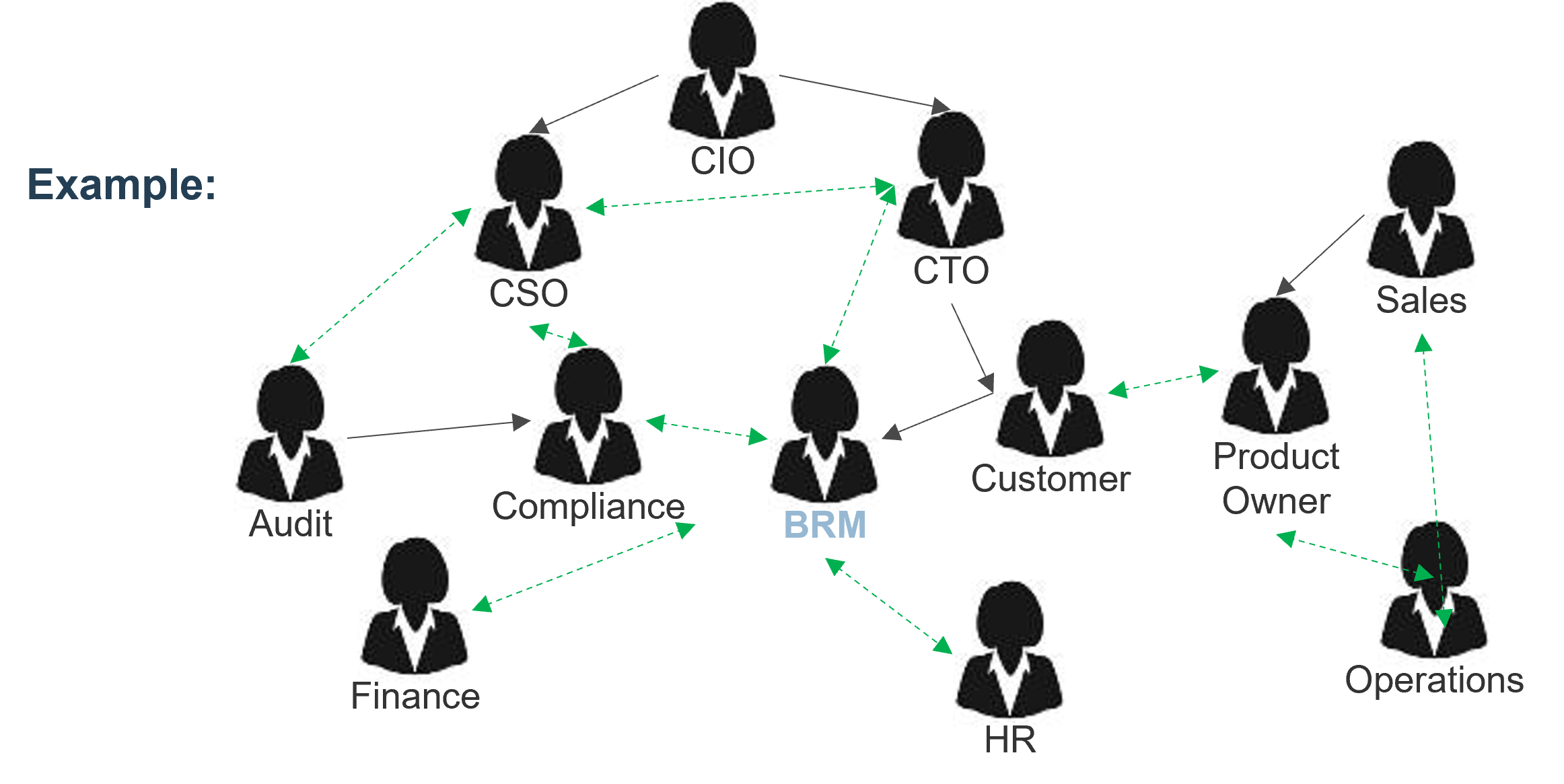

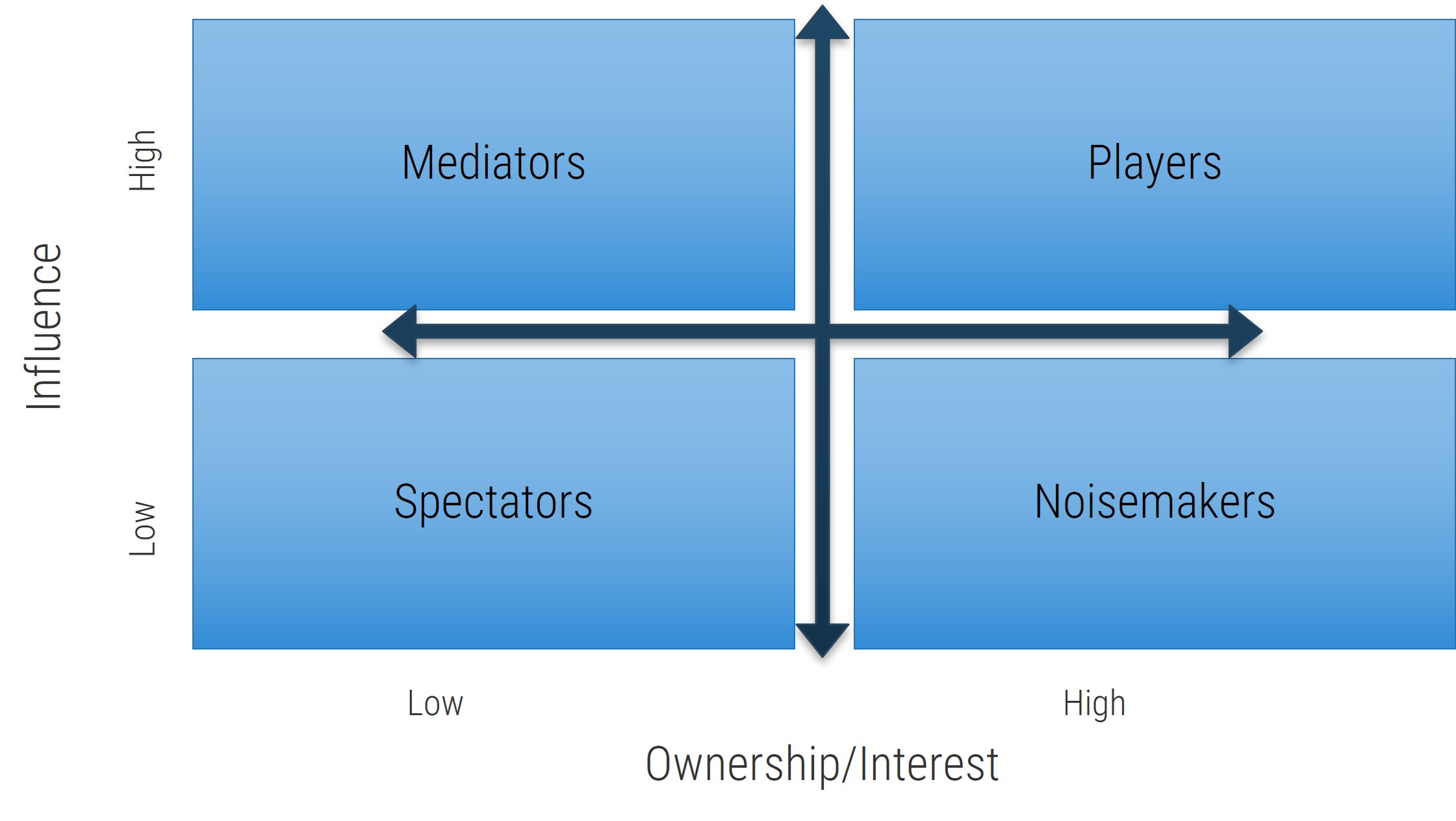

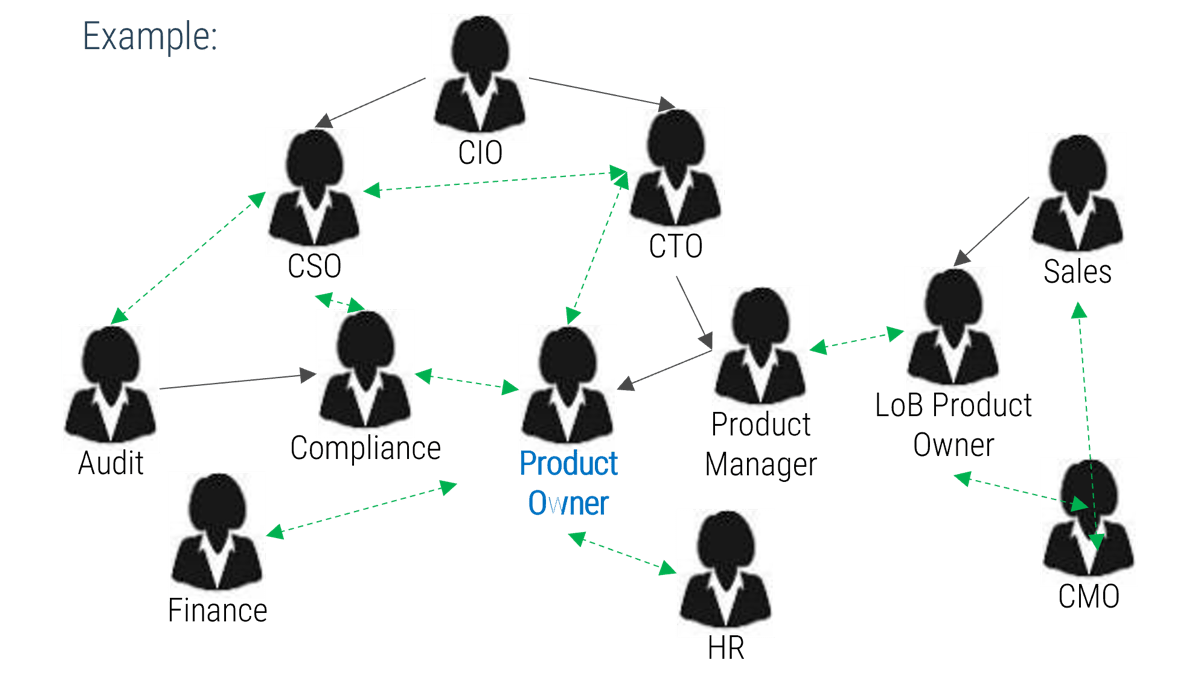

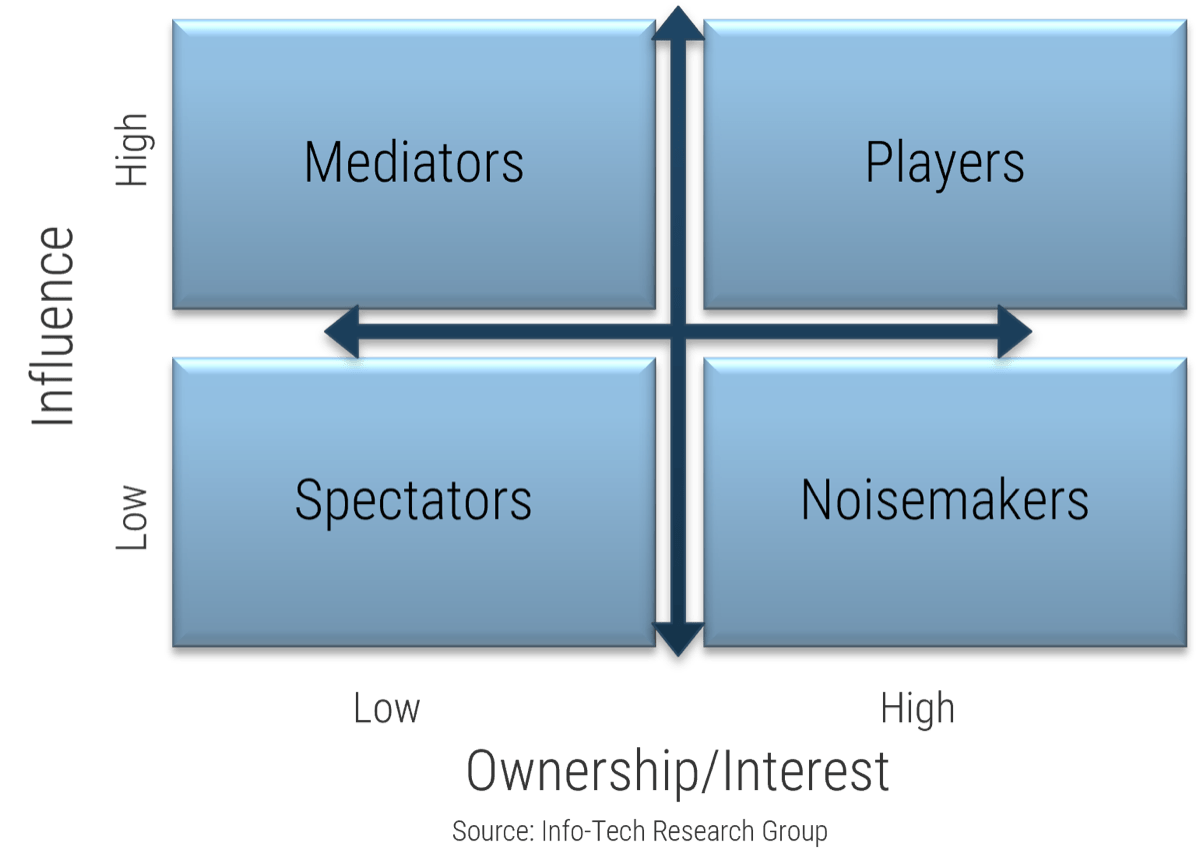

If resources are poorly managed, they prioritize work based on consequences rather than on meeting demand

As a result, matrix organizations are collectively steered by each resource and its individual motives, not by managers, executives, or organizational strategy.

In a matrix organization, demands on a resource’s time come from many directions, each demand unaware of the others. Resources are expected to prioritize their work, but they typically lack the authority to formally reject demand, so demand frequently outstrips the supply of work-hours the resource can deliver.

When this happens, the resource has three options:

- Work more hours, typically without compensation.

- Choose tasks not to do in a way that minimizes personal consequences.

- Diminish work quality to meet quantity demands.

The result is an unsustainable system for those involved:

- Resources cannot meet expectations, leading to frustration and disengagement.

- Managers cannot deliver on the projects or services they manage and struggle to retain skilled resources who are looking elsewhere for “greener pastures.”

- Executives cannot execute strategic plans as they lose decision-making power over their resources.

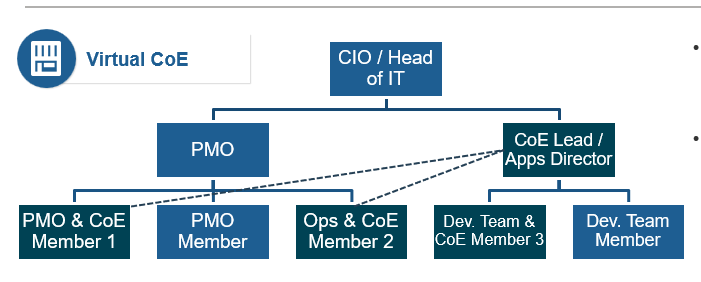

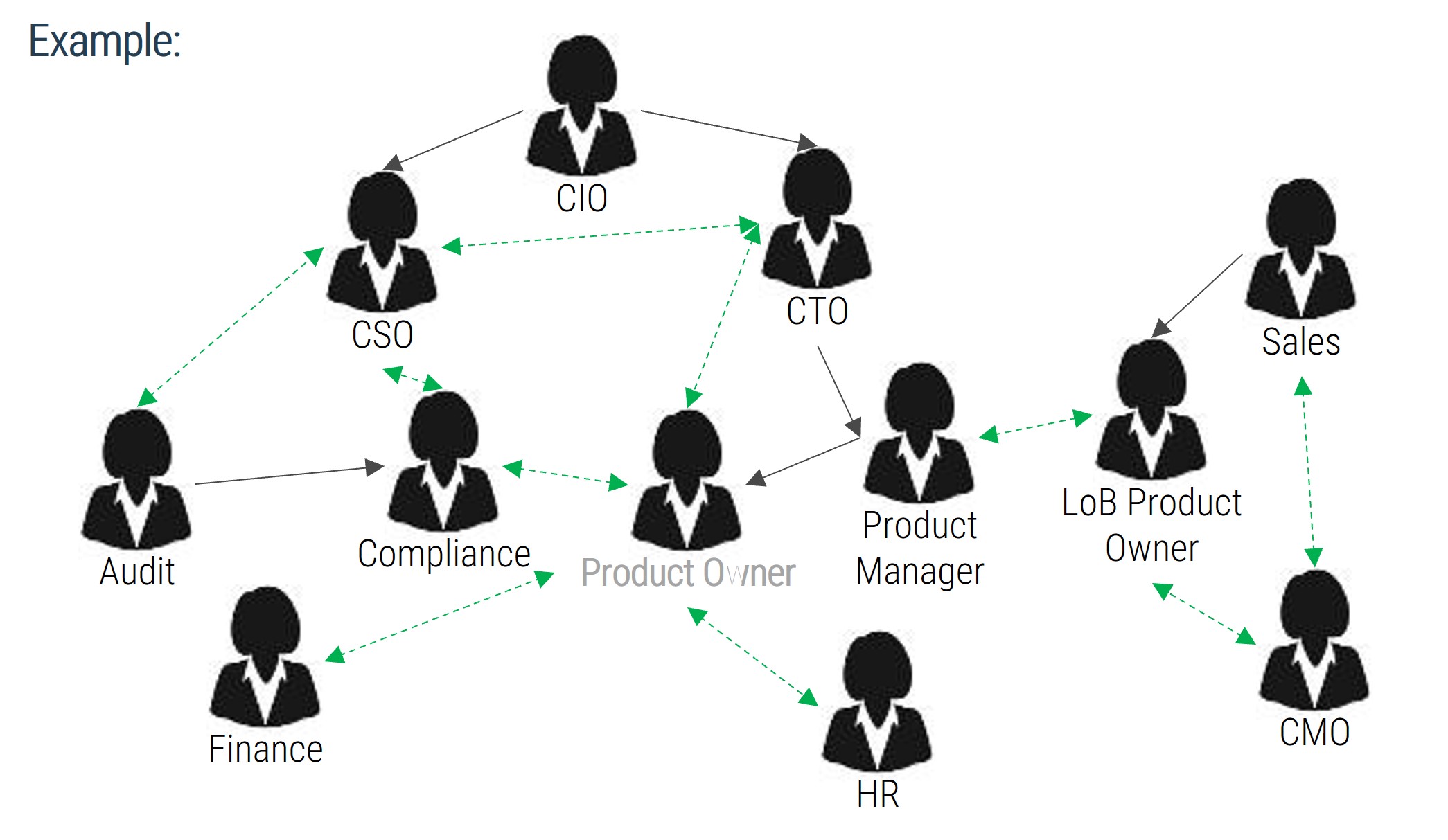

Scope your resource management practices within a matrix organization by asking “who?”

Resource management boils down to a seemingly simple question: how do we balance supply and demand? Balancing requires a decision maker to make choices; however, in a matrix organization, identifying this decision maker is not straightforward:

Balance

- Who decides how much capacity should be dedicated to project work versus administrative or operational work?

- Who decides how to respond to unexpected changes in supply or demand?

Supply

- Who decides how much total capacity we have for each necessary skill set?

- Who manages the contingency, or redundancy, of capacity?

- Who validates the capacity supply as a whole?

- Who decides what to report as unexpected changes in supply (and to whom)?

Demand

- Who generates demand on the resource that can be controlled by their manager?

- Who generates demand on the capacity that cannot be controlled by their manager?

- Who validates the demand on capacity as a whole?

- Who decides what to report as unexpected changes in demand (and to whom)?

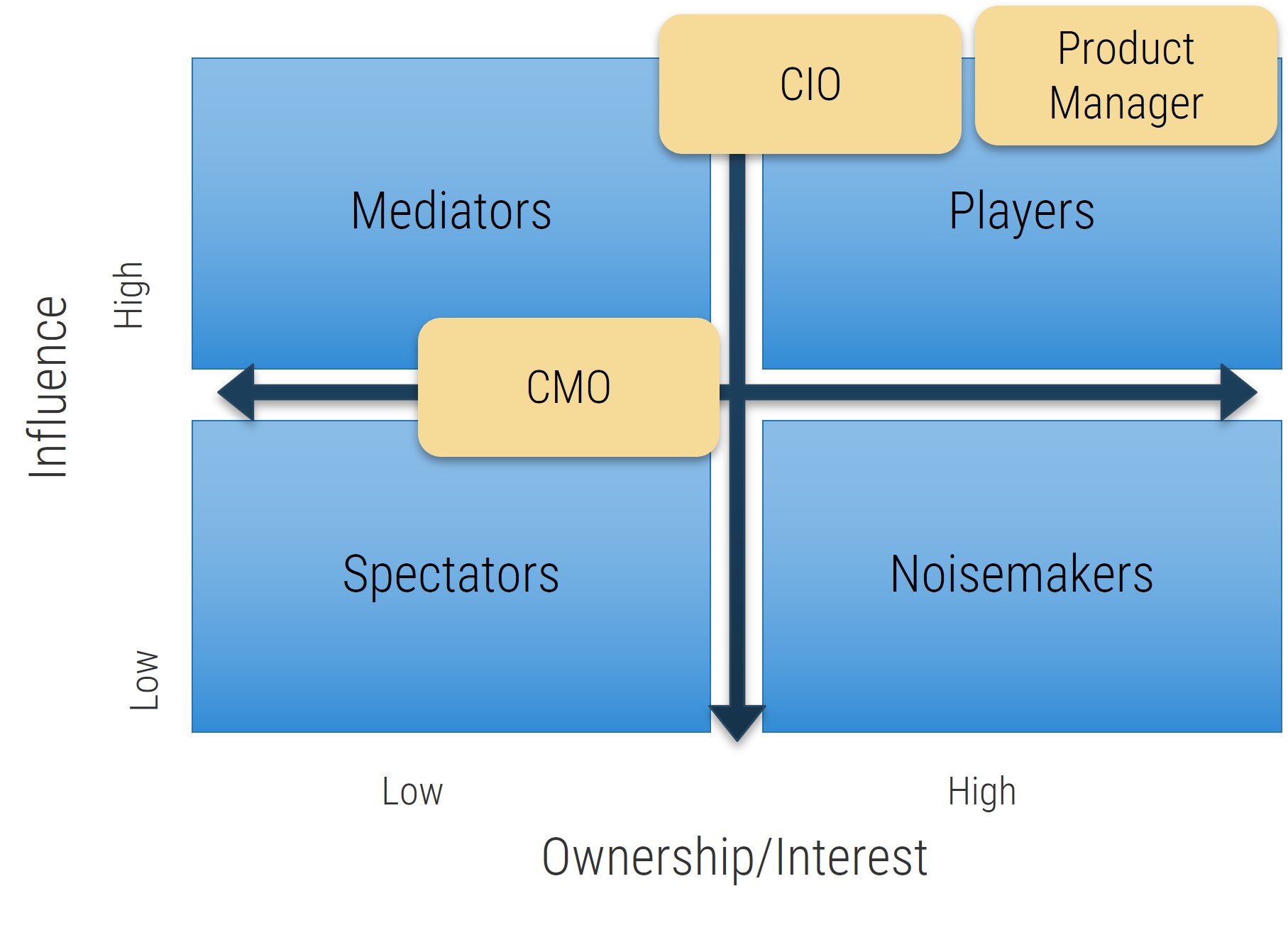

The individual who has the authority to make choices, and who is ultimately liable for those decisions, is an accountable person. In a matrix organization, accountability is dispersed, sometimes spilling over to those without the necessary authority.

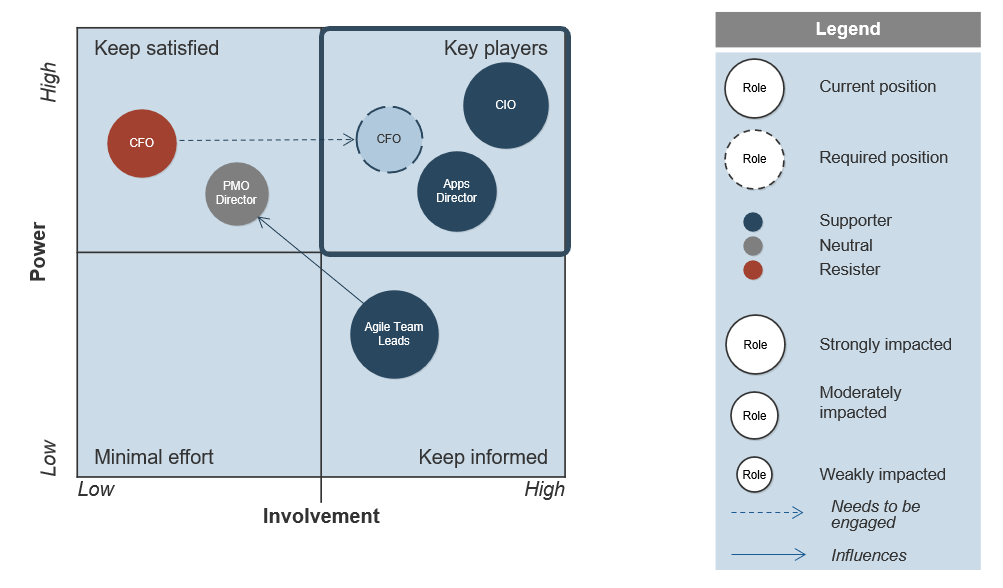

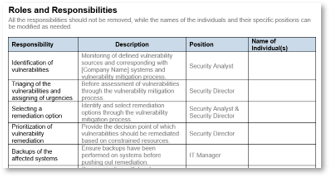

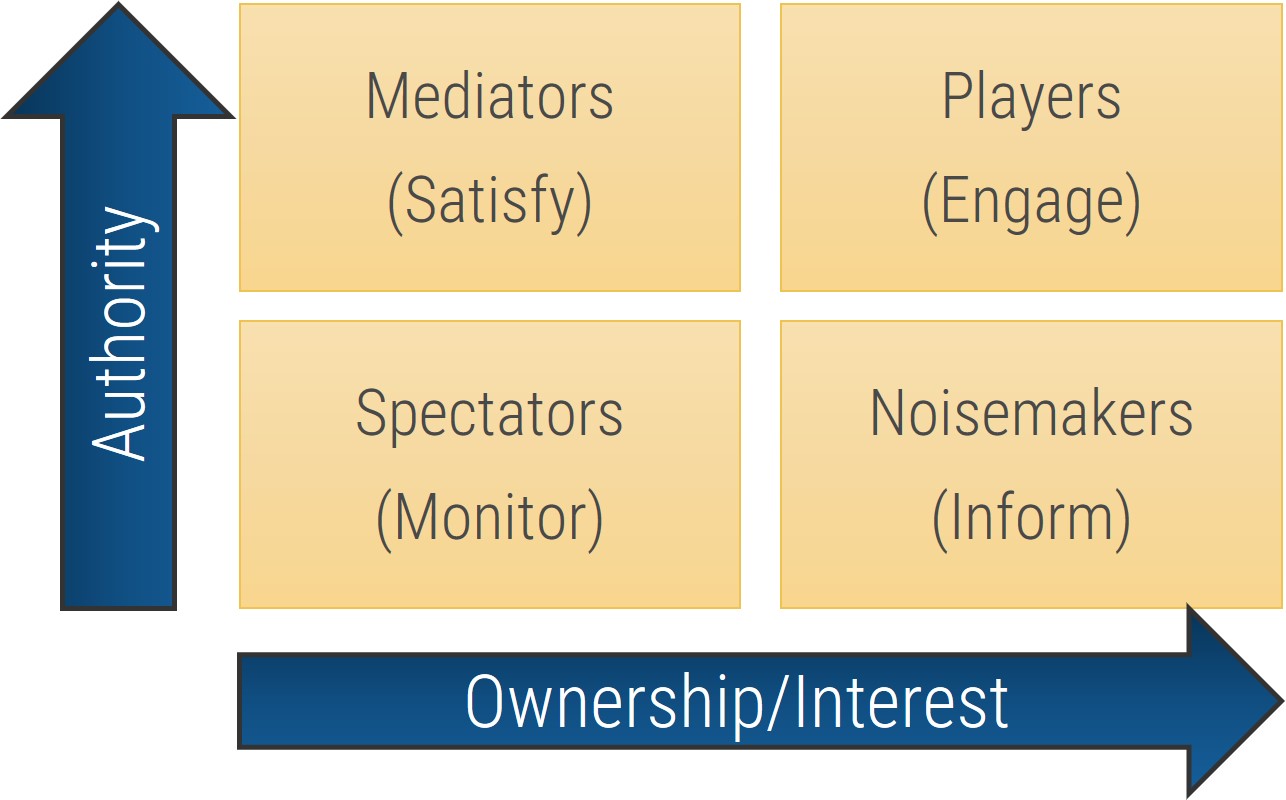

To effectively balance supply and demand, senior management must be held accountable

Differentiate between responsibility and accountability to manage the organization’s project portfolio effectively.

Responsibility

The responsible party is the individual (or group) who actually completes the task.

Responsibility can be shared.

VS.

Accountability

The accountable person is the individual who has the authority to make choices, and is ultimately answerable for the decision.

Accountability cannot be shared.

Resources often do not have the necessary scope of authority to make resource management choices, so they can never be truly accountable for the project portfolio. Instead, resources are accountable for making available trustworthy data, so the right people can make choices driven by organizational strategy.

The next activity will assess how accountability for resource management is currently distributed in your organization.

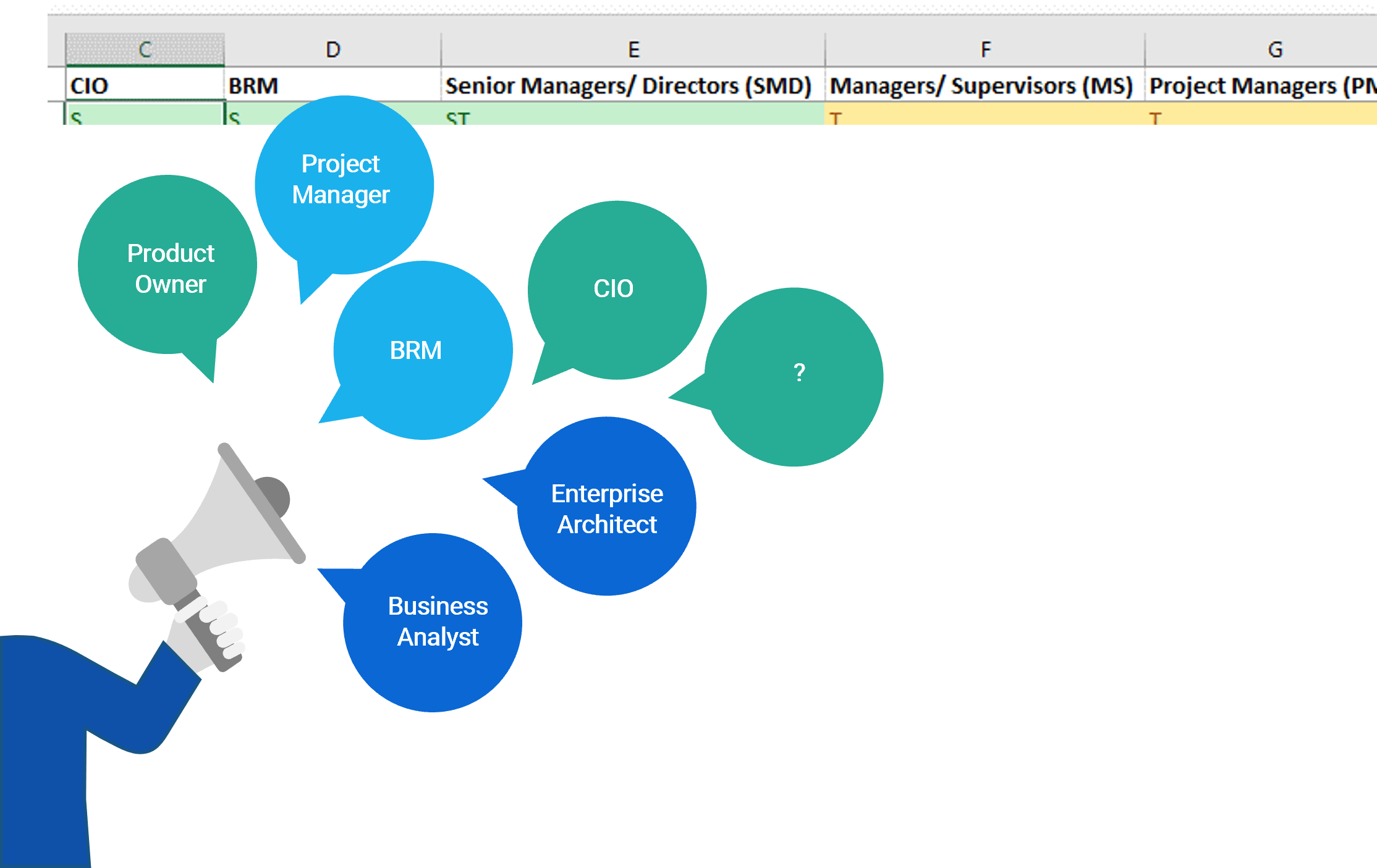

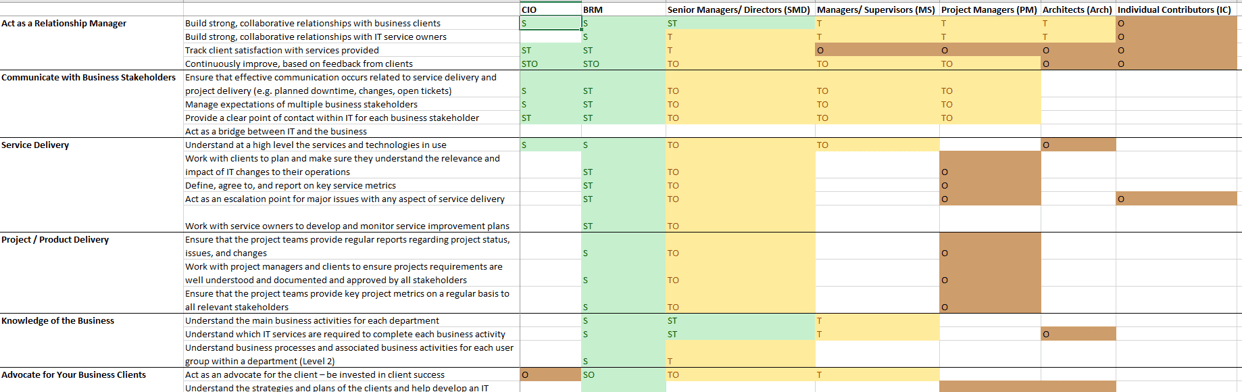

Assess the current distribution of accountability for resource management practice

1.1.2

15 minutes

Input

- Organizational strategy and culture

Output

- Current distribution of accountabilities for resource management

Materials

- Whiteboard/flip chart

- Markers

Participants

- CIO

- PMO Director/ Portfolio Manager

Below is a list of tasks in resource management that require choices. Discuss who is currently accountable and whether they have the right authority and ability to deliver on that accountability.

| Resource management tasks that require choices

|

Accountability

|

| Current

|

Effective?

|

| Identify all demands on resources

|

|

|

| Prioritize identified project demands

|

|

|

| Prioritize identified operational demands

|

|

|

| Prioritize identified administrative demands

|

|

|

| Prioritize all of the above demands

|

|

|

| Enumerate resource supply

|

|

|

| Validate resource supply

|

|

|

| Collect and validate supply and demand data

|

|

|

| Defer or reject work beyond available supply

|

|

|

| Adjust resource supply to meet demand

|

|

|

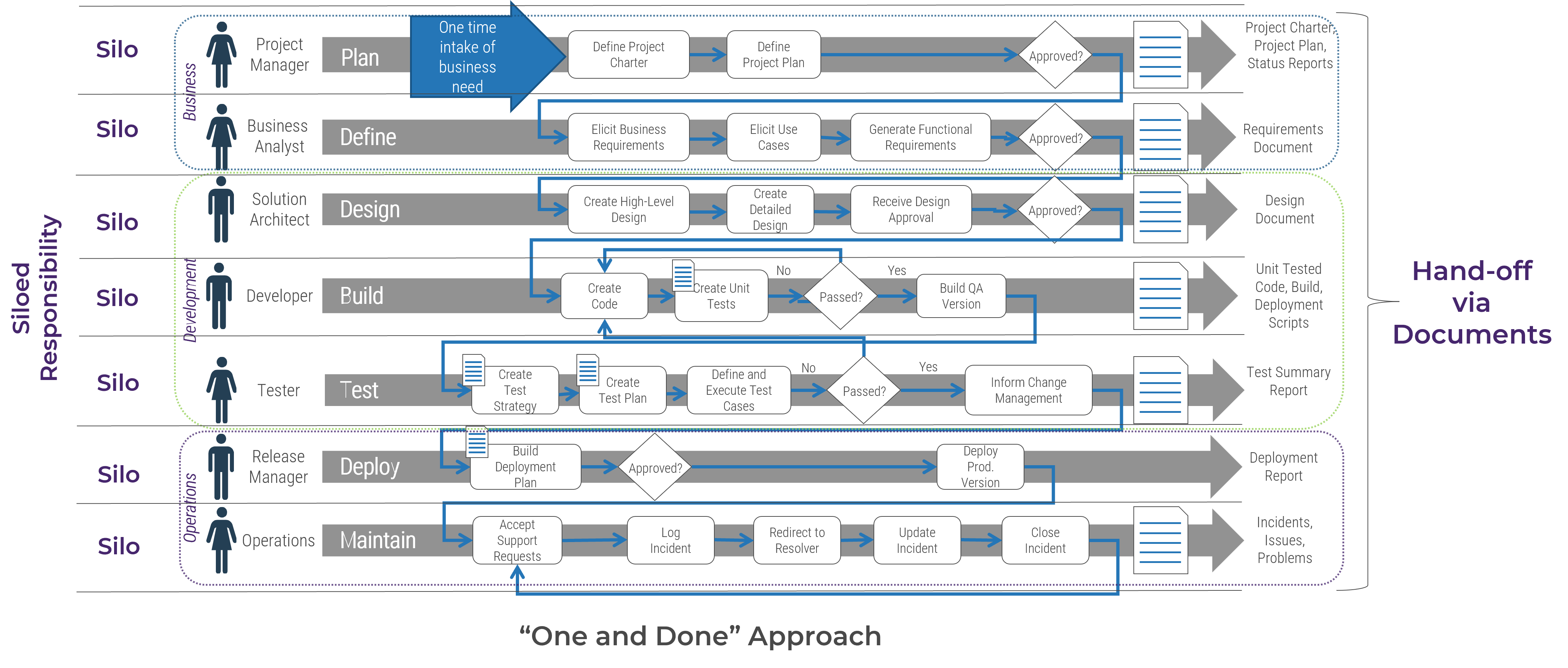

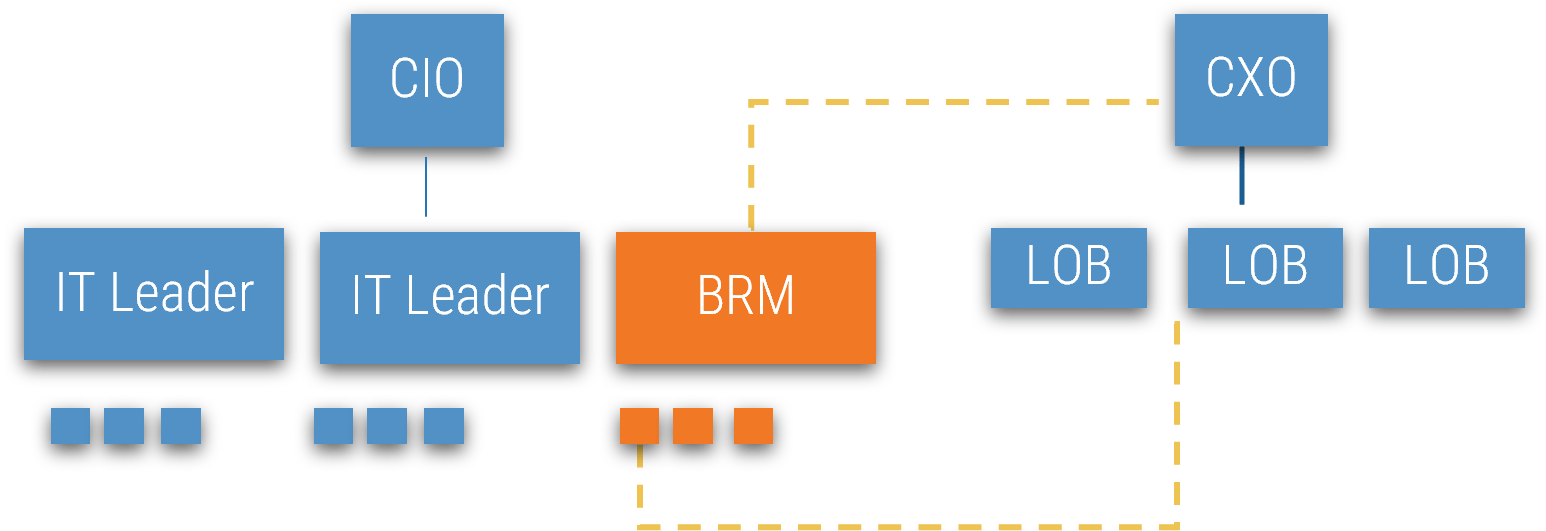

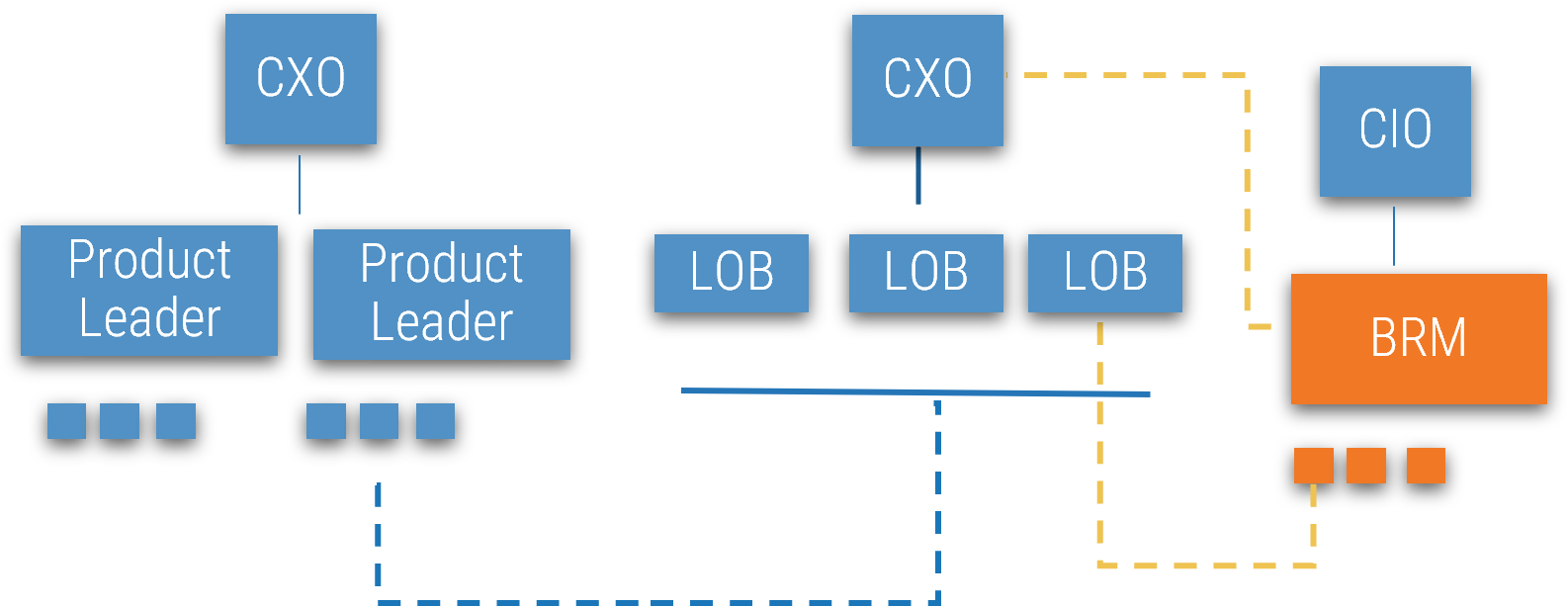

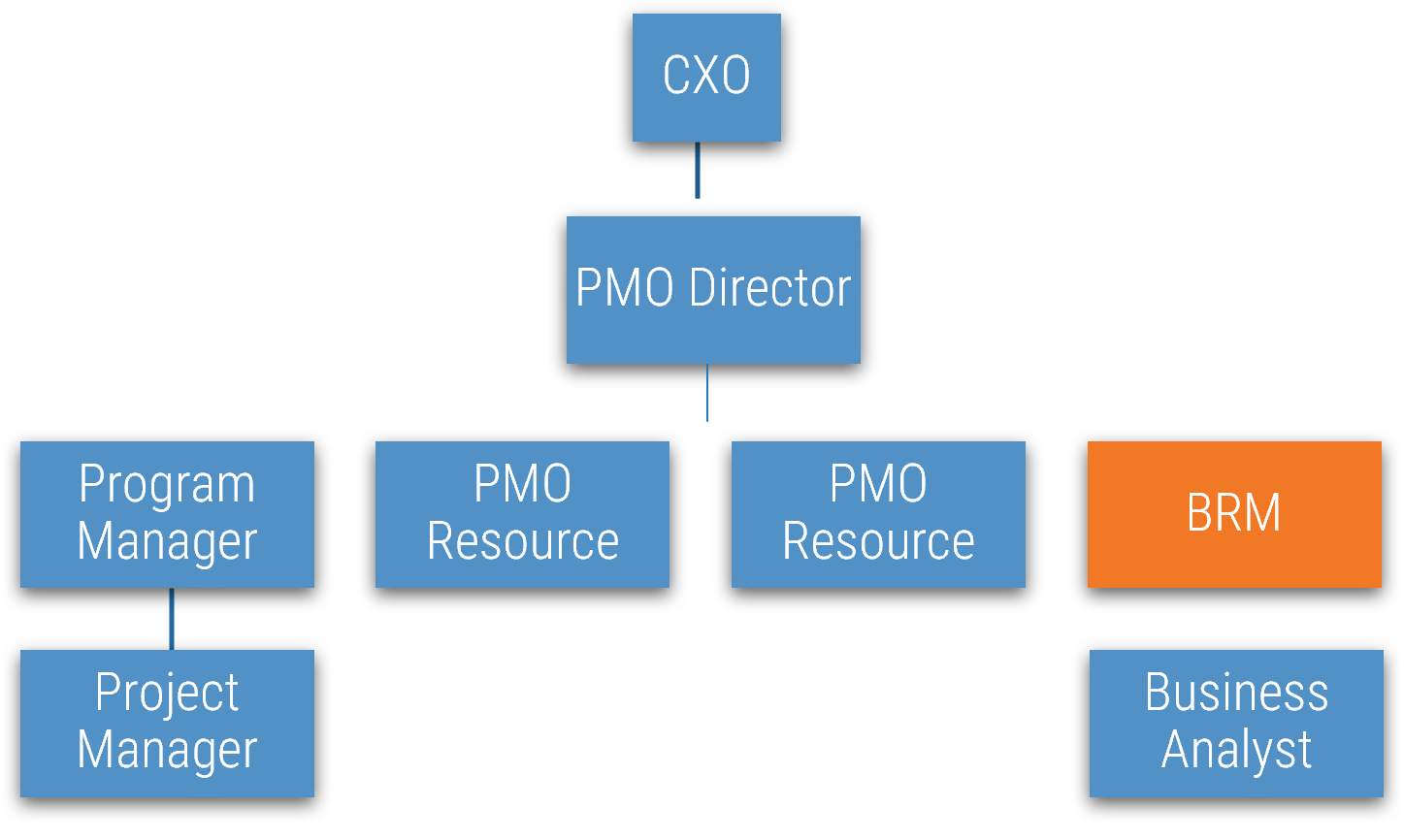

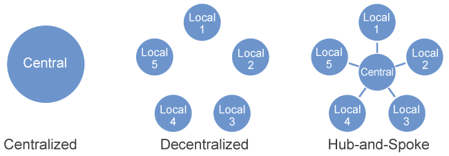

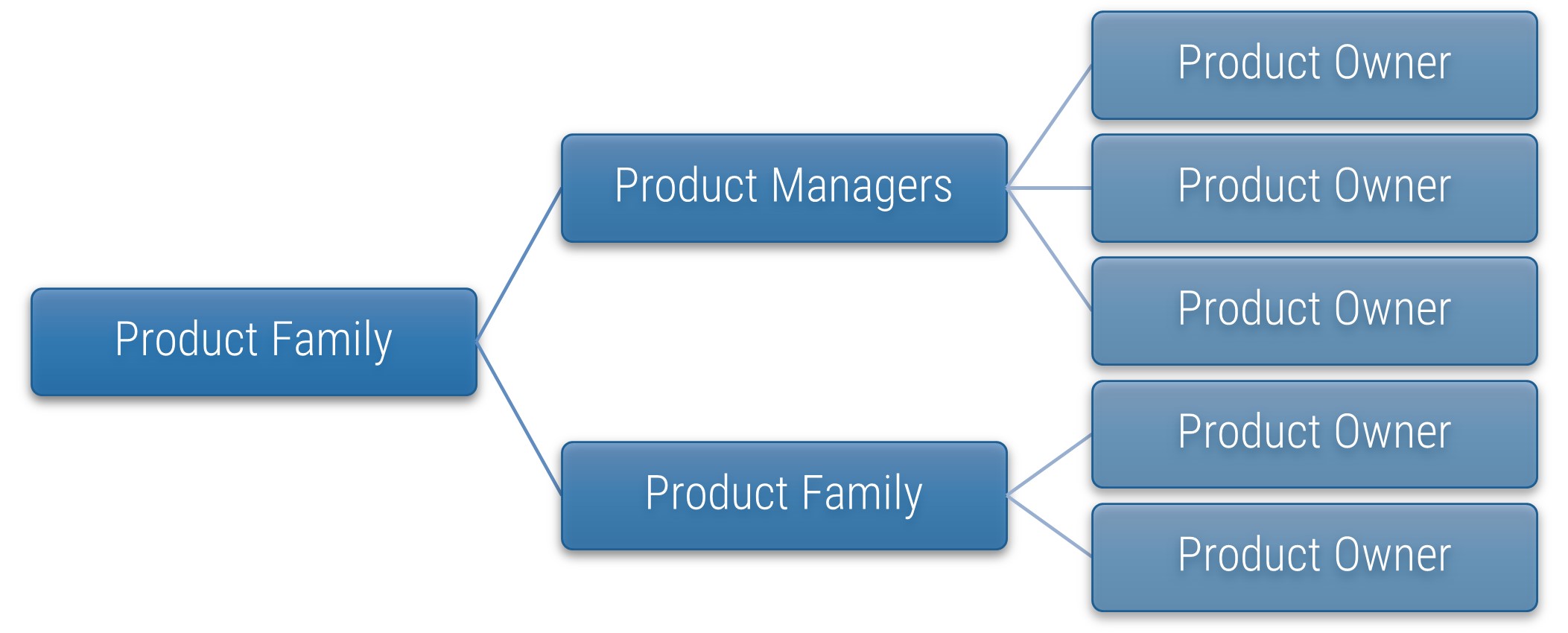

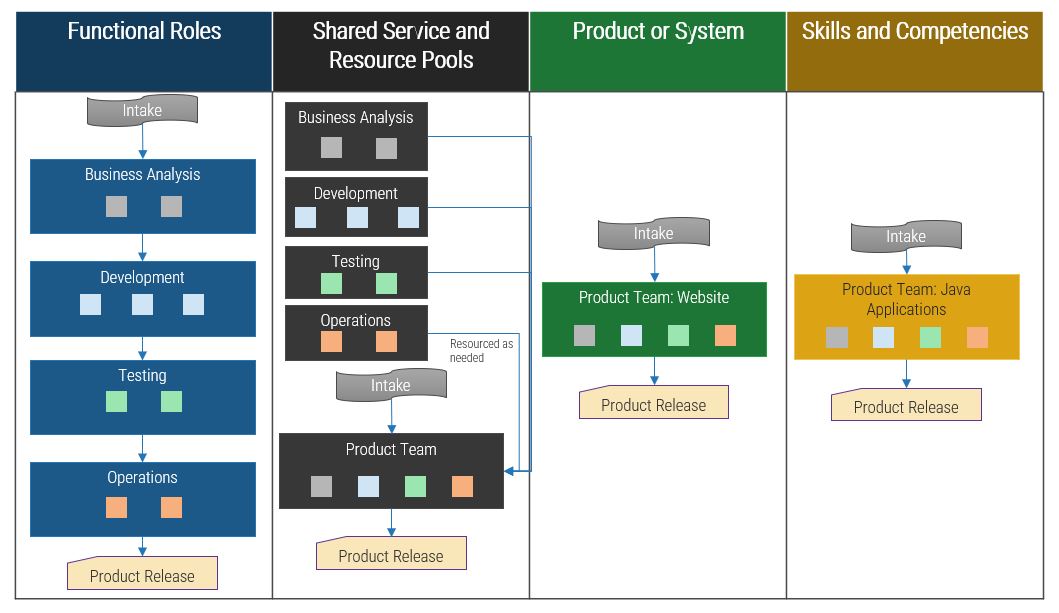

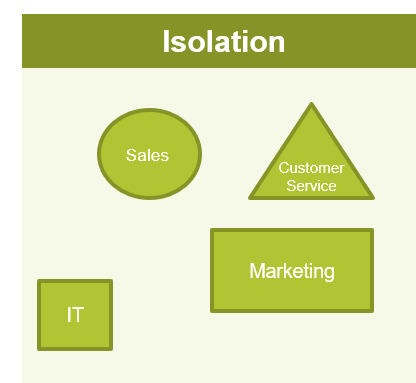

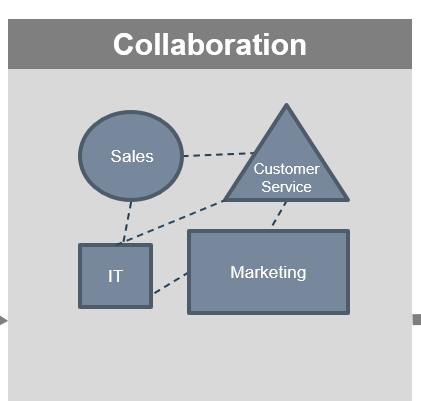

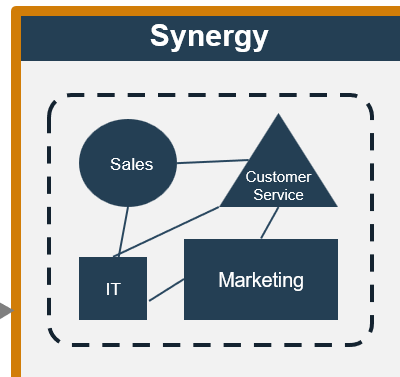

Develop coordination between project and functional managers to optimize resource management

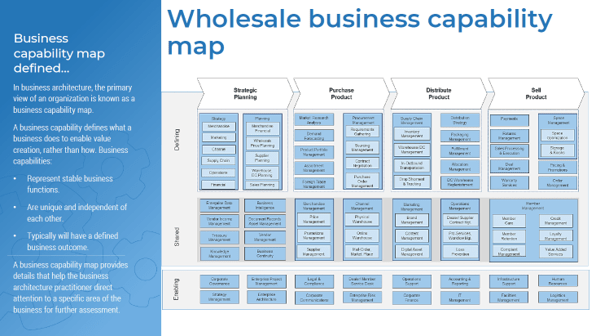

Because resources are invariably responsible for both project and non-project work, efforts to procure capacity for projects cannot exist in isolation.

IT departments need many different technical skill sets at their disposal for their day-to-day operations and services, as well as for projects. A limited hiring budget for IT restricts the number of hires with any given skill, forcing IT to share resources between service and project portfolios.

This resource sharing produces a matrix organization divided along the lines of service and projects. Functional and project managers provide respective oversight for services and projects. Resources split their available work-hours toward service and project tasks according to priority –

in theory.

However, in practice, two major challenges exist:

- Poor coordination between functional and project managers causes commitments beyond resource capacity, disputes about resource oversight, and animosity among management, all while resources struggle to balance unclear priorities.

- Resources have a “third boss,” namely uncontrolled demands from the rest of the business, which lack both visibility and accountability.

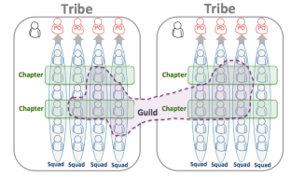

Resource management processes must account for the numerous small demands generated in a matrix organization

Avoid going bankrupt $20 at a time: small demands add up to a significant chunk of work-hours.

Because resource managers must cover both projects and services within IT, the typical solution to allocation problems in matrix organizations is to escalate the urgency and severity of demands by involving the executive steering committee. Unfortunately, the steering committee cannot expend time and resources on all demands. Instead, they often set a minimum threshold for cases – 100-1,000 work-hours depending on the organization.

Under this resource management practice, small demands – especially the quick-fixes and little projects from “the third boss” – continue to erode project capacity. Eventually, projects fail to get resources because pesky small demands have no restrictions on the resources they consumed.

Realistic resource management needs to account for demand from all three bosses; however…

Info-Tech Insight

Excess project or service request intake channels lead to the proliferation of “off-the-grid” projects and tasks that lack visibility from the IT leadership. This can indicate that there may be too much red tape: that is, the request process is made too complex or cumbersome. Consider simplifying the request process and bring IT’s visibility into those requests.

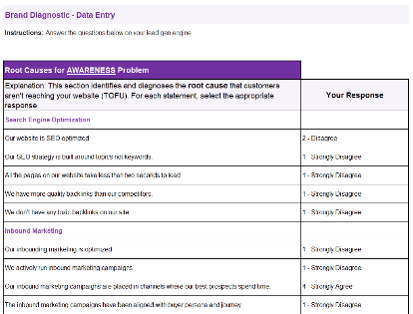

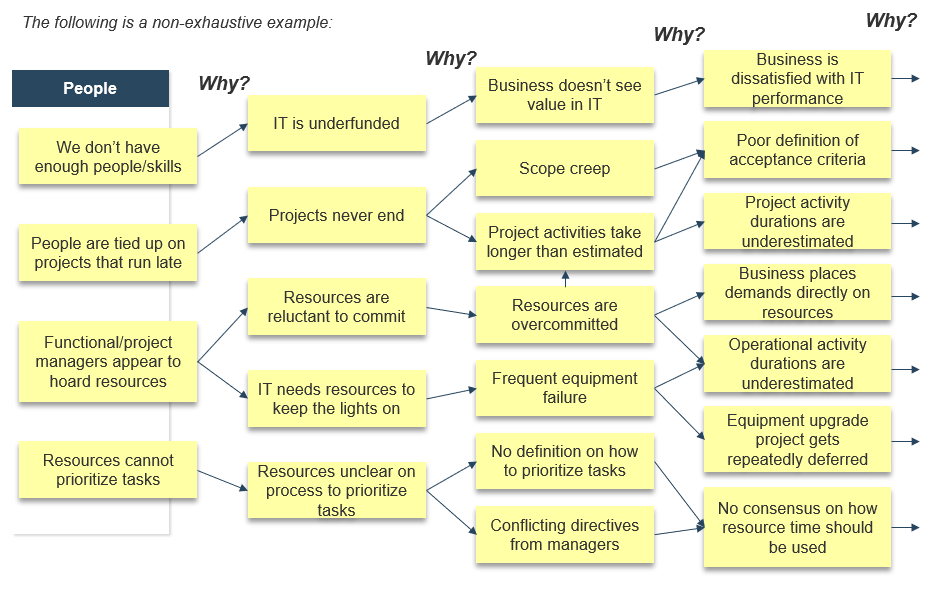

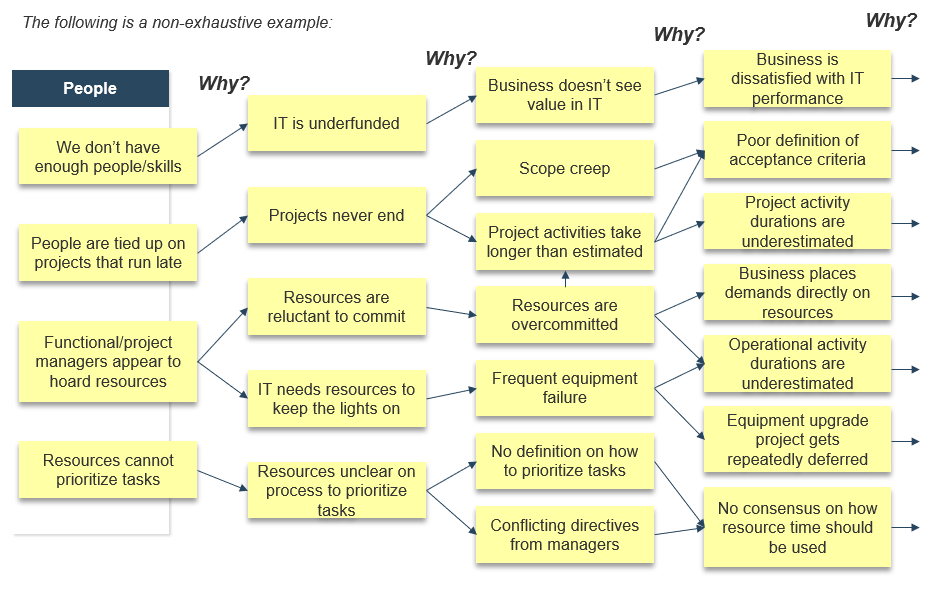

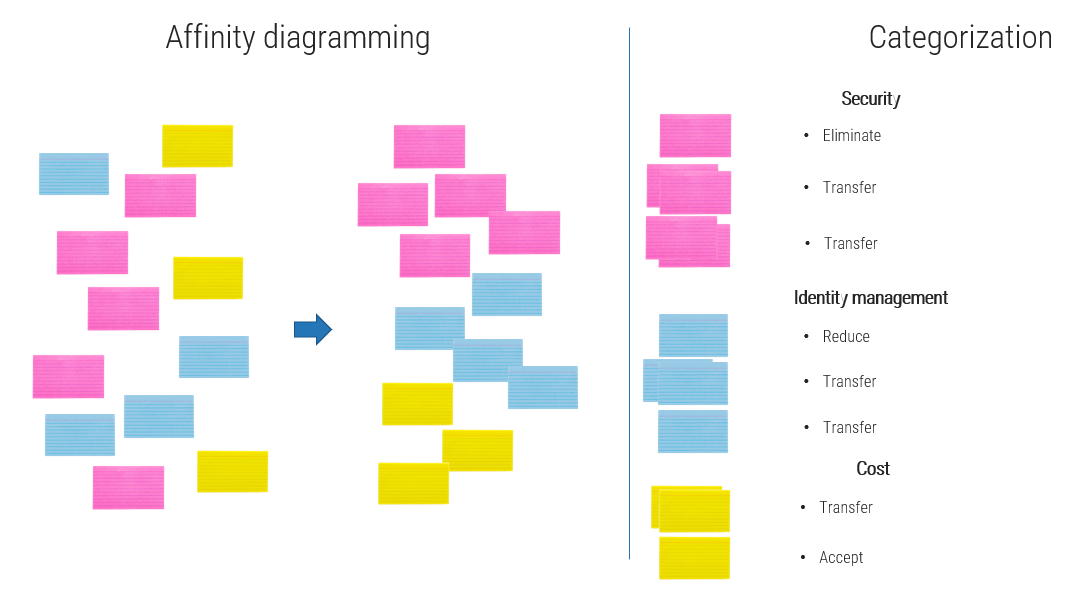

Interrogate your resource management problems to uncover root causes

1.1.3

30 minutes to 1 hour

Input

- Organizational strategy and culture

Output

- Root causes of resource management failures

Materials

- Whiteboard/flip chart

- Sticky notes

- Markers

Participants

- CIO

- PMO Director/ Portfolio Manager

- Functional Managers

- Project Managers

- Pick a starting problem statement in resource management.

e.g. projects can’t get resource work-hours.

- Ask the participants “why”? Use three generic headings – people, processes, and technology – to keep participants focused. Keep the responses solution-agnostic: do not jump to solutions. If you have a large group, divide into smaller groups and use sticky notes to encourage more participation in this brainstorming step.

| People

|

Processes

|

Technology

|

- We don’t have enough people/skills.

- People are tied up on projects that run late.

- Functional and project managers appear to hoard resources.

- Resources cannot prioritize work.

|

- Resources are too busy responding to 911s from the business.

- Resources cannot prioritize projects vs. operational tasks.

- “Soft-closed” projects do not release resources for other work.

|

- We don’t have tools that show resource availability.

- Tools we have for showing resource availability are not being used.

- Data is inaccurate and unreliable.

|

- Determine the root cause by iteratively asking “why?” up to five times, or until the chain of whys comes full circle. (i.e. Why A? B. Why B? C. Why C? A.)

See below for an example.

1.1.2 Example of a root-cause analysis: people

The following is a non-exhaustive example:

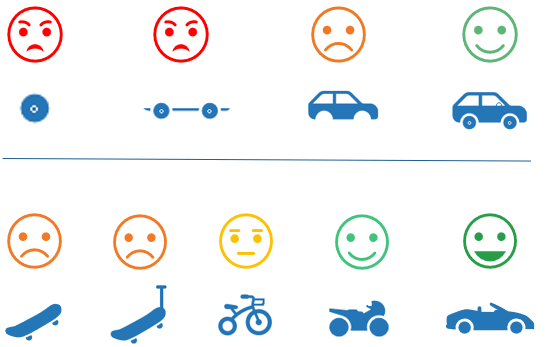

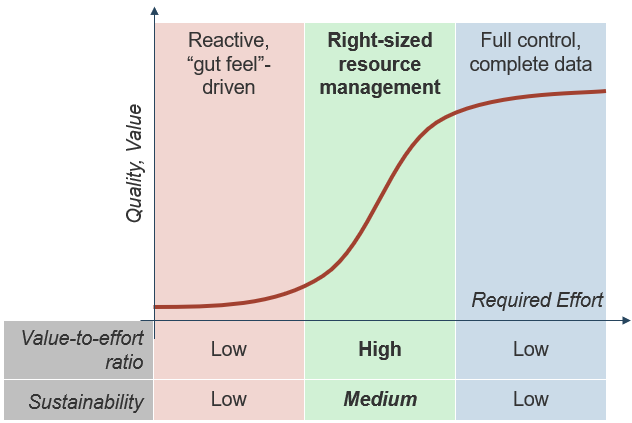

Right-size your resource management strategy with Info-Tech’s realistic resource management practice

If precise, accurate, and complete data on resource supply and demand was consistently available, reporting on project capacity would be easy. Such data would provide managers complete control over a resource’s time, like a foreman at a construction site. However, this theoretical scenario is incompatible with today’s matrixed workplace:

- Sources of demand can lie outside IT’s control.

- Demand is generated chaotically, with little predictability.

- Resources work with minimal supervision.

Collecting and maintaining resource data is therefore nearly impossible:

- Achieving perfect data accuracy creates unnecessary overhead.

- Non-compliance by one project or resource makes your entire data set unusable for resource management.

This blueprint will guide you through right-sizing your resource management efforts to achieve maximum value-to-effort ratio and sustainability.

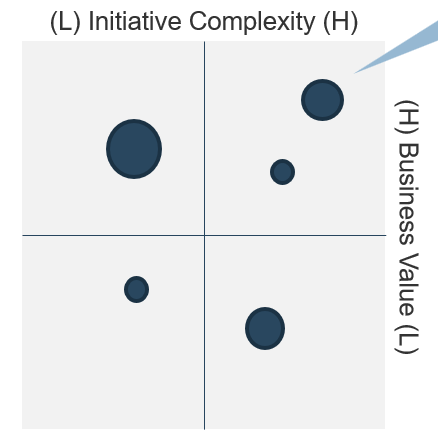

Choose your resource management course of action

Portfolio managers looking for a resource management solution have three mutually exclusive options:

Option A: Do Nothing

- Rely on expert judgment and intuition to make portfolio choices.

- Allow the third boss to dictate the demands of your resources.

Option B: Get Precise

- Aim for granularity and precision of data with a solution that may demand more capacity than is realistically available by hiring, outsourcing, or over-allocating people’s time.

- Require detailed, accurate time sheets for all project tasks.

- For those choosing this option, proceed to Info-Tech’s Select and Implement a PPM Solution.

Option C: Get Realistic

- Balance capacity supply and demand using abstraction.

- Implement right-sized resource management practices that rely on realistic, high-level capacity estimates.

- Reduce instability in data by focusing on resource capacity, rather than granular project demands and task level details.

This blueprint takes you through the steps necessary to accomplish Option C, using Info-Tech’s tools and templates for managing your resources.

Step 1.2: Create realistic estimates of supply and demand

PHASE 1

1.1 Set a course of action

1.2 Estimate supply and demand

PHASE 2

2.1 Select resource management dimensions

2.2 Select resource management tools

2.3 Build process steps

PHASE 3

3.1 Pilot your process for viability

3.2 Plan stakeholder engagement

This step will walk you through the following activities:

- Create a realistic estimate of project capacity

- Map all sources of demand on resources at a high level

- Validate your supply and demand assumptions by directly surveying your resources

This step involves the following participants:

- PMO Director / Portfolio Manager

- Project Managers (optional)

- Functional / Resource Managers (optional)

- Project Resources (optional)

Outcomes of this step

- A realistic estimate of your total and project capacity, as well as project and non-project demand on their time

- Quantitative insight into the resourcing challenges facing the organization

- Results from a time-tracking survey, which are used to validate the assumptions made for estimating resource supply and demand

Create a realistic estimate of your project capacity with Info-Tech’s Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator

Take an iterative approach to capacity estimates: use your assumptions to create a meaningful estimate, and then validate with your staff to improve its accuracy.

Use Info-Tech’s Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator to create a realistic estimate of your project capacity.

The calculator tool requires minimal upfront staff participation: you can obtain meaningful results with participation from even a single person, with insight on the distribution of your resources and their average work week or month. As the number of participants increases, the quality of analysis will improve.

The first half of this step guides you through how to use the calculator. The second half provides tactical advice on how to gather additional data and validate your resourcing data with your staff.

Download Info-Tech’s Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator

Info-Tech Insight

What’s first, process or tools? Remember that process determines the quality of your data while data quality limits the tool’s utility. Without quality data, you cannot evaluate the success of the tool, so nail down your collection process first.

Break down your resource capacity into high-level buckets of time for each role

1.2.1

30 minutes - 1 hour

Input

- Staff resource types

- Average work week

- Estimated allocations

Output

A realistic estimate of project capacity

Materials

Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator

Participants

- PMO Director

- Resource/Functional Managers (optional)

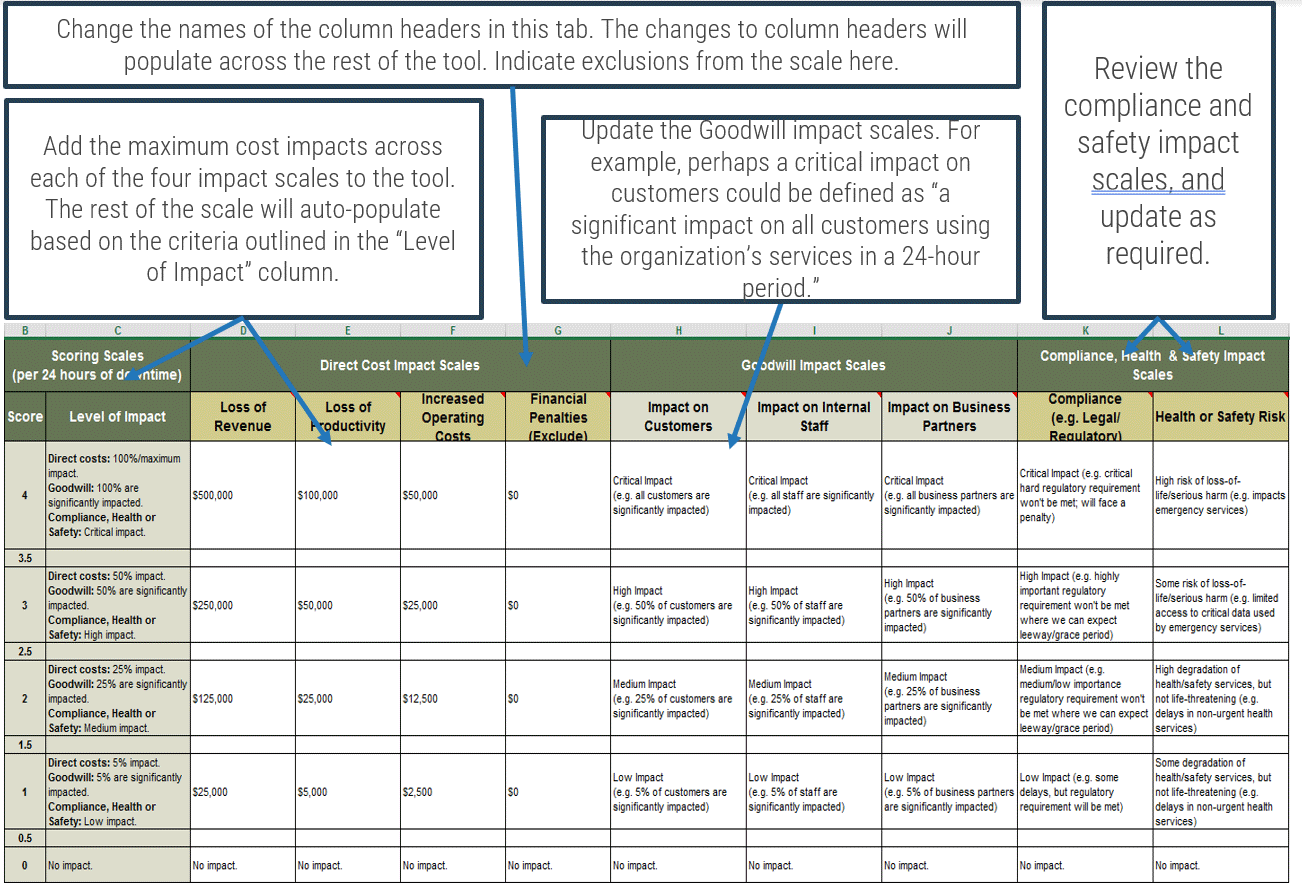

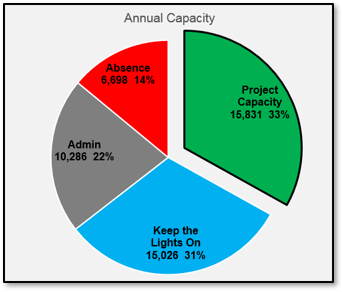

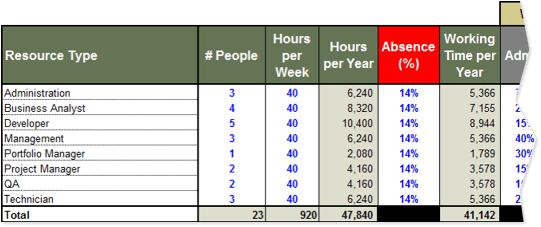

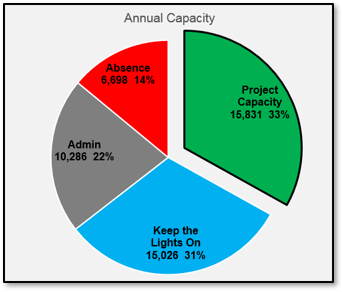

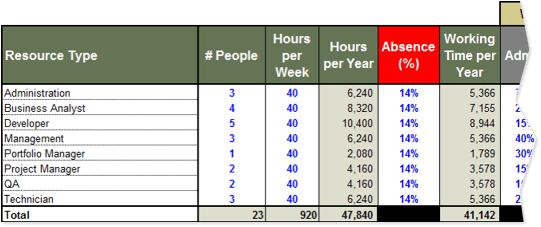

We define four high-level buckets of resource time:

- Absence: on average, a resource spends 14% of the year on vacation, statutory holidays, business holidays and other forms of absenteeism.

- Administrative: time spent on meetings, recordkeeping, etc.

- Operational: keeping the lights on; reactive work.

- Projects: time to work on projects; typically, this bucket of time is whatever’s left from the above.

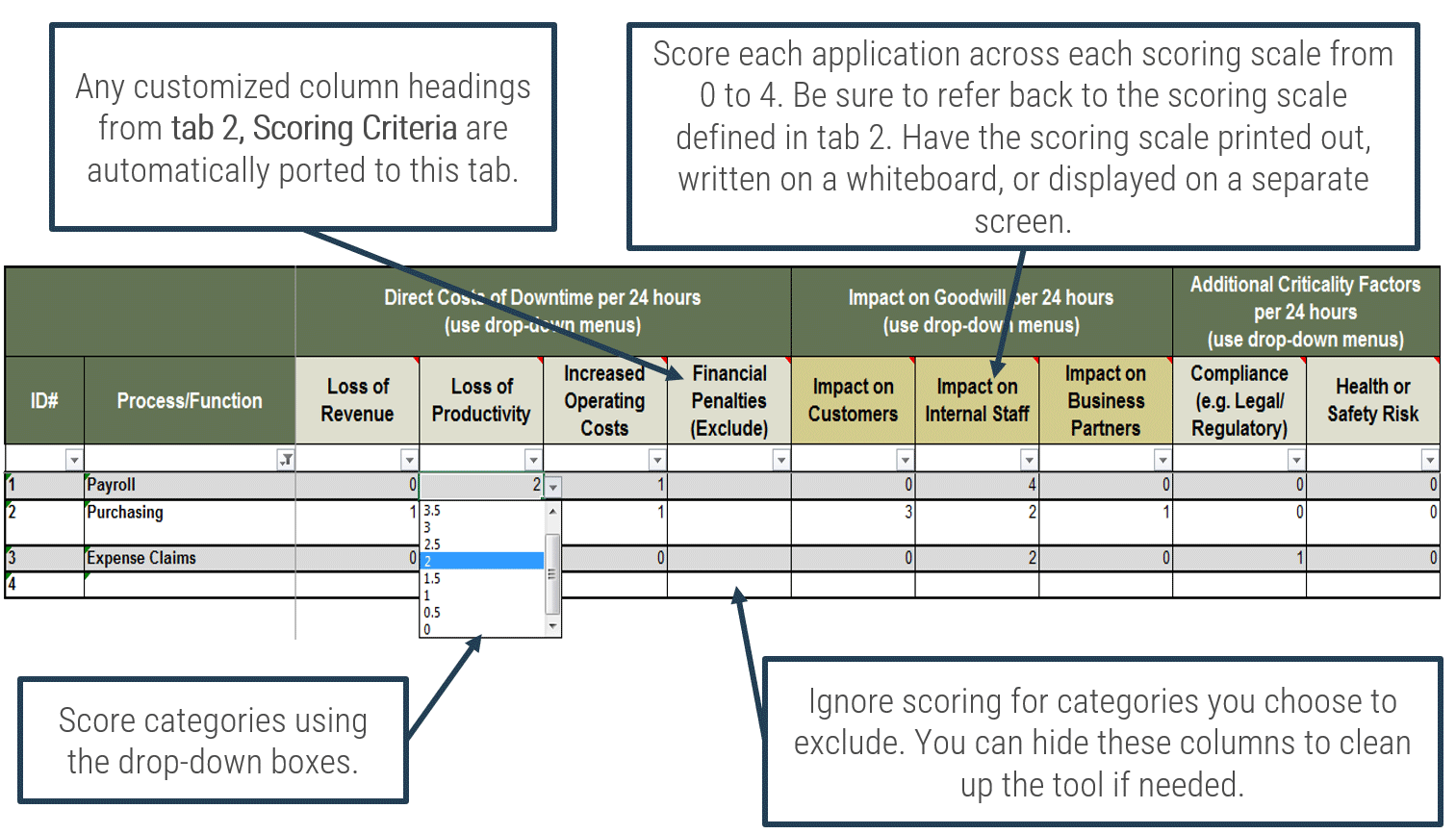

Instructions for working through Tab 2 of the Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator are provided in the next two sections. Follow along to obtain your breakdown of annual resource capacity in a pie chart.

Break down your resource capacity into high-level buckets of time for each role

1.2.1

Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator, Tab 2: Capacity Supply

Discover how many work-hours are at your disposal by first accounting for absences.

- Compile a list of each of the roles within your department.

- Enter the number of staff currently performing each role.

- Enter the number of hours in a typical work week for each role.

- Enter the foreseeable out-of-office time (vacation, sick time, etc.) Typically, this value is 12-16% depending on the region.

Hours per Year represents your total resource capacity for each role, as well as the entire department. This column is automatically calculated.

Working Time per Year represents your total resource capacity minus time employees are expected to spend out of office. This column is automatically calculated.

Info-Tech Insight

Example for a five-day work week:

- 2 weeks (10 days) of statutory holidays

- 3 weeks of vacation

- 1.4 weeks (7 days) of sick days on average

- 1 week (5 days) for company holidays

Result: 7.4/52 weeks’ absence = 14.2%

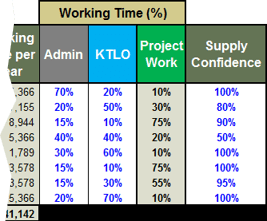

Break down your resource capacity into high-level buckets of time for each role (continued)

1.2.1

Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator, Tab 2: Capacity Supply

Determine the current distribution of your resources’ time and your confidence in whether the resources indeed supply those times.

5. Enter the percentage of working time across each role that, on an annual basis, goes toward administrative duties (non-project meetings, training, time spent checking email, etc.) and keep-the-lights-on work (e.g. support and maintenance work).

While these percentages will vary by individual, a high-level estimate across each role will suffice for the purposes of this activity.

6. Express how confident you are in each resource being able to deliver the calculated project work hours in percentages.

Another interpretation for supply confidence is “supply control”: estimate your current ability to control this distribution of working time to meet the changing needs in percentages.

Percentage of your working time that goes toward project work is calculated based upon what’s left after your non-project working time allocations have been subtracted.

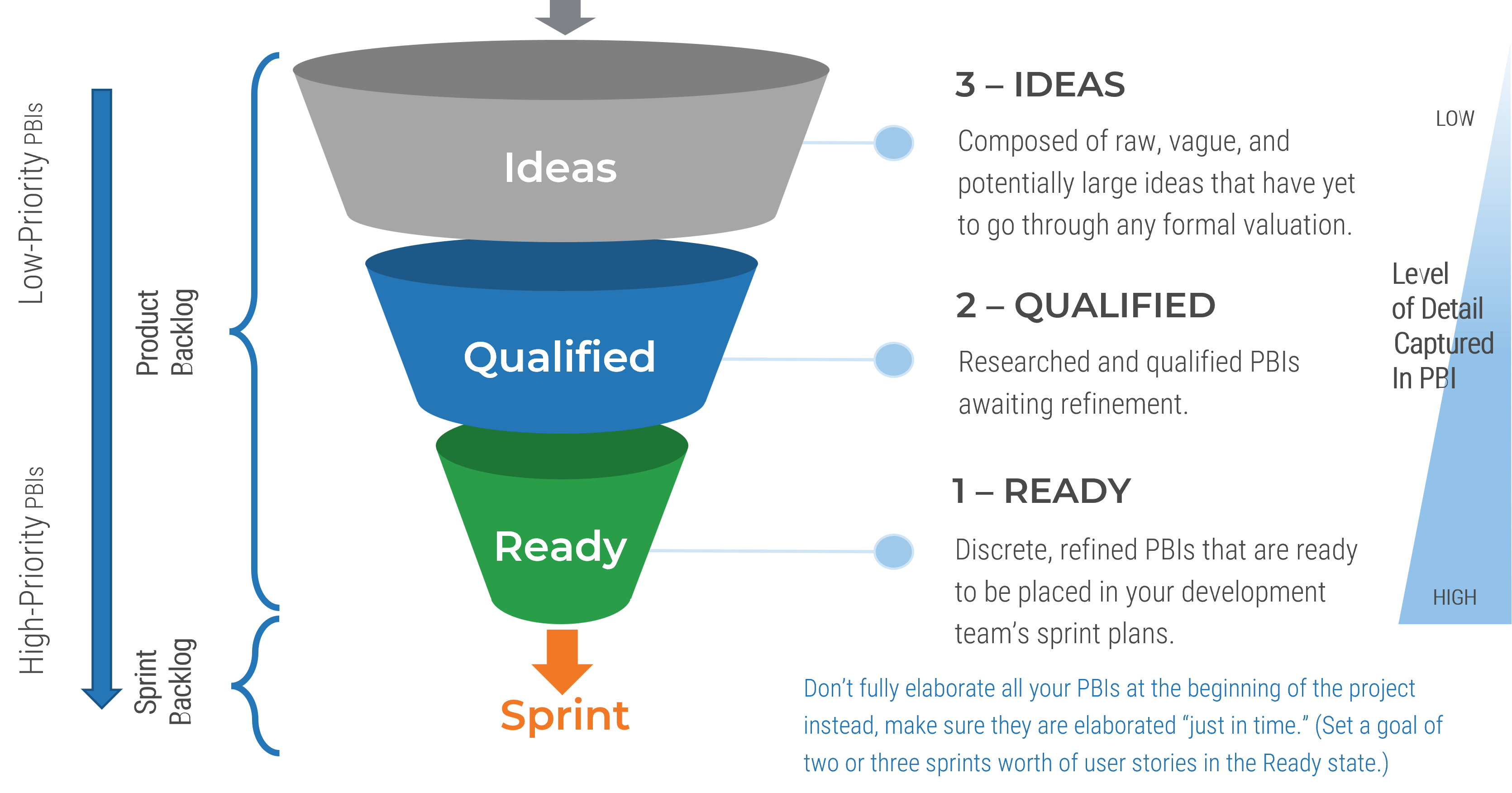

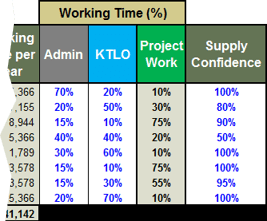

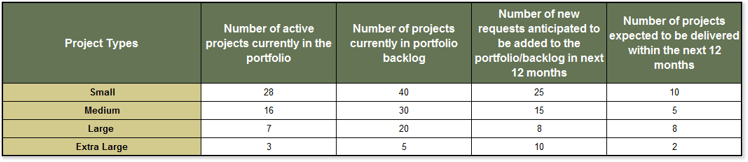

Create a realistic estimate of the demand from your project portfolio with the T-shirt sizing technique

1.2.2

15 minutes - 30 minutes

Input

- Average work-hours for a project

- List of projects

- PPM Current State Scorecard

Output

A realistic estimate of resource demand from your project portfolio

Materials

Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator

Participants

- PMO Director

- Project Managers (optional)

Quickly re-express the size of your project portfolio in resource hours required.

Estimating the resources required for a project in a project backlog can take a lot of effort. Rather than trying to create an accurate estimate for each project, a set of standard project sizes (often referred to as the “T-shirt sizing” technique) will be sufficiently accurate for estimating your project backlog’s overall demand.

Instructions for working through Tab 3 of the tool are provided here and in the next section.

1. For each type of project, enter the average number for work-hours.

| Project Types

|

Average Number of Work Hours for a Project

|

| Small

|

80

|

| Medium

|

200

|

| Large

|

500

|

| Extra-Large

|

1000

|

Improve your estimate of demand from your project portfolio by accounting for unproductive capacity spending

1.2.2

Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator, Tab 3: Project Demand

2. Using your list of projects, enter the number of projects for each appropriate field.

3. Enter your resource waste data from the PPM Current State Scorecard (see next section). Alternatively, enter your best guess on how much project capacity is spent wastefully per category.

Info-Tech Insight

The calculator estimates the project demand by T-shirt-sizing the work-hours required by projects to be delivered within the next 12 months and then adding the corresponding wasted capacity. This may be a pessimistic estimate, but it is more realistic because projects tend to be delivered late more than early.

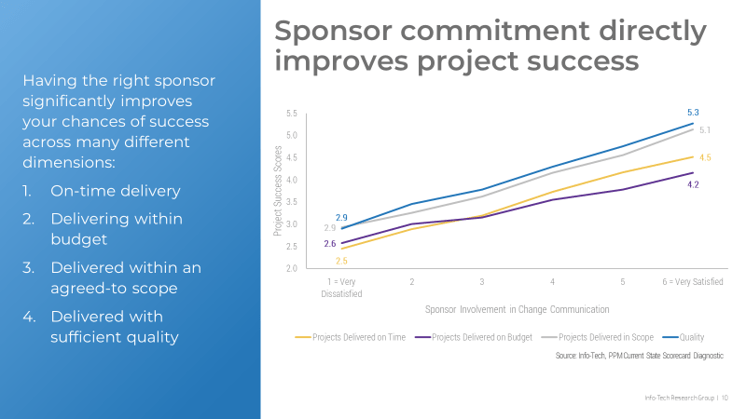

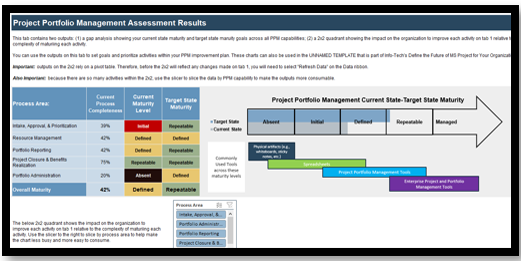

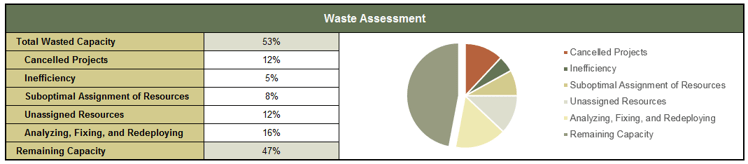

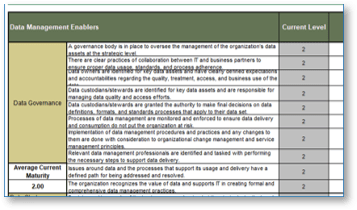

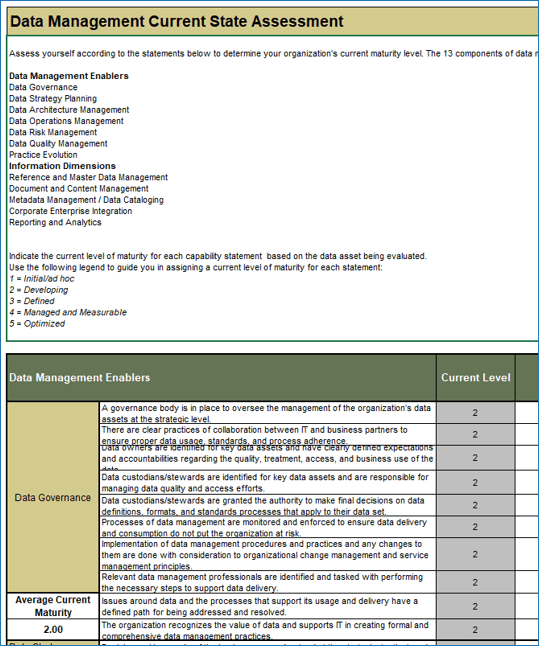

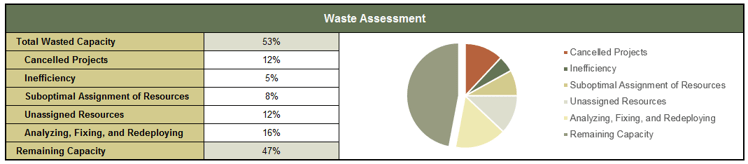

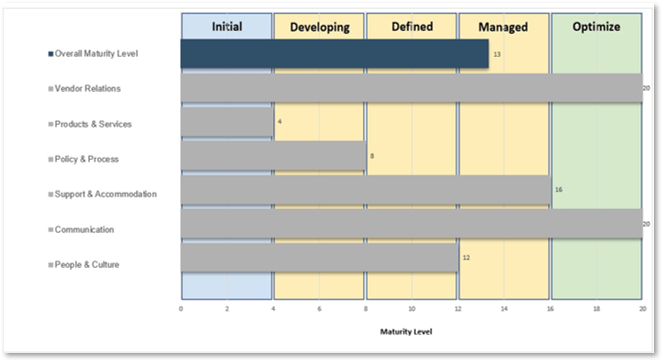

Estimate how much project capacity is wasted with Info-Tech’s PPM Current State Scorecard

Call 1-888-670-8889 or contact your Account Manager for more information.

This step is highly recommended but not required.

Info-Tech’s PPM Current State Scorecard diagnostic provides a comprehensive view of your portfolio management strengths and weaknesses, including project portfolio management, project management, customer management, and resource utilization.

Use the wisdom-of-the-crowd to estimate resource waste in:

- Cancelled projects

- Inefficiency

- Suboptimal assignment of resources

- Unassigned resources

- Analyzing, fixing, and redeploying

50% of PPM resource is wasted on average, effectively halving your available project capacity.

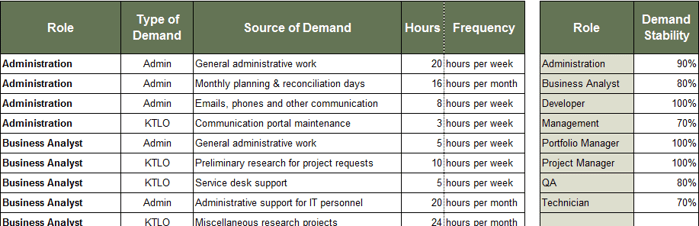

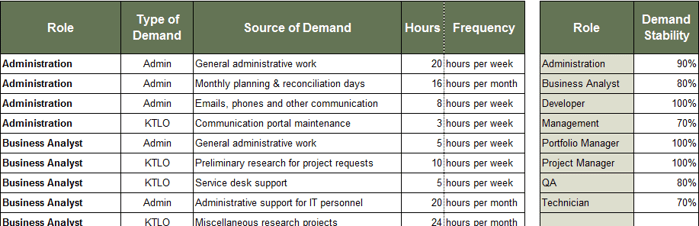

Estimate non-project demand on your resources by role

1.2.3

45 minutes - 1 hour

Input

- Organizational chart

- Knowledge of staff non-project demand

Output

Documented non-project demands and their estimated degree of fluctuation

Materials

Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator

Participants

- PMO Director

- Functional Managers (optional)

Document non-project demand that could eat into your project capacity.

When discussing project demands, non-project demands (administrative and operational) are often underestimated and downplayed – even though, in reality, they take a de facto higher priority to project work. Use Tab 4 of the tool to document these non-project demands, as well as their sources.

1. Choose a role using a drop-down list.

2. Enter the type and the source of the demand.

3. Enter the size and the frequency of the demand in hours.

4. Estimate how stable the non-project demands are for each role.

Examine and discuss your supply-demand analysis report

1.2.4

30 minutes - 1 hour

Input

Completed Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator

Output

Supply-Demand Analysis Report

Materials

Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator

Participants

- PMO Director

- Functional Managers

- Project Managers

Start a data-driven discussion on resource management using the capacity supply-demand analysis report.

Tab 5 of the calculator is a report that contains the following analysis:

- Overall resource capacity supply and demand gap

- Project capacity supply vs. demand gap

- Non-project capacity supply vs. demand balance

- Resource capacity confidence

Each analysis is described and explained in the following four sections. Examine the report and discuss the following among the activity participants:

- How is your perception of the current resource capacity supply-demand balance affected by this analysis? How is it confirmed? Is it changed?

- Perform a root-cause analysis of problems revealed by the report. For each observation, ask “why?” repeatedly – generally, you can arrive at the root cause in four iterations.

- Refer back to Activity 1.1.2: current distribution of accountability for resource management. In your situation, how would you prioritize which resource management tasks to improve? Who are the involved stakeholders?

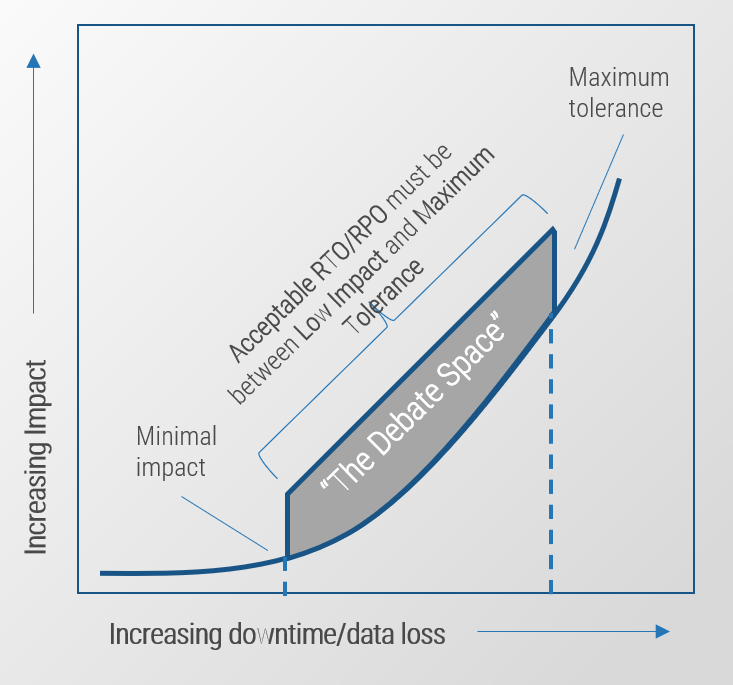

Examine your supply-demand analysis report: overall resource capacity gap

1.2.4

Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator, Tab 5: Supply-Demand Analysis

1. Examine your resource capacity supply and demand gap.

The top of the report on Tab 5 shows a breakdown of your annual resource supply and demand, with resource capacity shown in both total hours and percentage of the total. For the purposes of the analysis, absence is averaged. If total demand is less than available resource supply, the surplus capacity will be displayed as “Free Capacity” on the demand side.

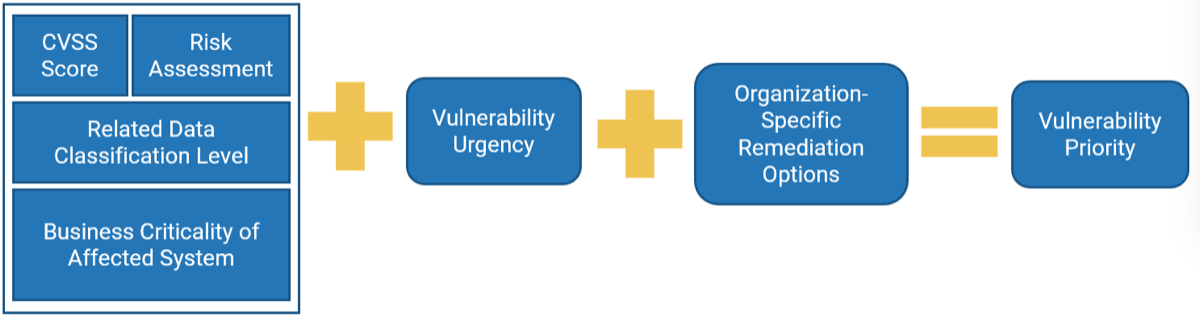

The Supply & Demand Analysis table displays the realistic project capacity, which is calculated by subtracting non-project supply deficit from the project capacity. This is based on the assumption that all non-project work must get done. The difference between the project demand and the realistic project capacity is your supply-demand gap, in work-hours.

If your supply-demand gap is zero, recognize that the project demand does not take into account the project backlog: it only takes into account the projects that are expected to be delivered within the next 12 months.

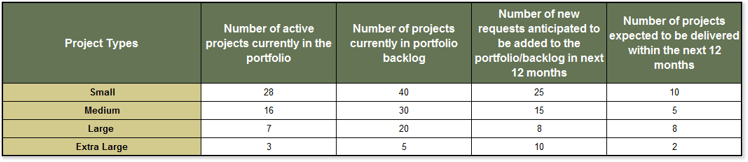

Examine your supply-demand analysis report: project capacity gap

1.2.4

Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator, Tab 5: Supply-Demand Analysis

2. Examine your project capacity supply vs. demand gap.

The project capacity supply and demand analysis compares your available annual project capacity with the size of your project portfolio, expressed in work-hours.

The supply side is further broken down to productive vs. wasted project capacity. The demand side is broken down to three buckets of projects: those that are active, those that sit in the backlog, and those that are expected to be added within 12 months. Percentage values are expressed in terms of total project capacity.

A key observation here is the limitation to which reducing wasteful spending of resources can get to the project portfolio backlog. In this example, even a theoretical scenario of 100% productive project capacity will not likely result in net shrinkage of the project portfolio backlog. To achieve that, either the total project capacity must be increased, or less projects must be approved.

Note: the work-hours necessary for delivering projects that are expected to be completed within 12 months is not shown in this visualization, as they should be represented within the other three categories of projects.

Examine your supply-demand analysis report: non-project capacity gap

1.2.4

Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator, Tab 5: Supply-Demand Analysis

3. Drill down on the non-project capacity supply-demand balance by each role.

The non-project capacity supply and demand analysis compares your available non-project capacity and their demands in a year, for each role, in work-hours.

With this chart, you can:

- Observe which roles are “running hot,” (i.e. they have more demand than available supply).

- Verify your non-project/project supply ratio assumptions in Tab 2 of the tool / Activity 1.2.1.

Tab 5 also provides similar breakdowns for administrative and keep-the-lights-on capacity supply and demand by each role.

Examine your supply-demand analysis report: resource capacity confidence (RCC)

1.2.4

Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator, Tab 5: Supply-Demand Analysis

4. Examine your resource capacity confidence.

In our approach, we introduce a metric called Resource Capacity Confidence (RCC). Conceptually, RCC is defined as follows:

Resource Capacity Confidence = SC × DS × SDR

| Term

|

Name

|

Description

|

| SC

|

Supply Control

|

How confident are you that the supply of your resources’ project capacity will be delivered?

|

| DS

|

Demand Stability

|

How wildly does demand fluctuate? If it cannot be controlled, can it be predicted?

|

| SDR

|

Supply-Demand Ratio

|

How severely does demand outstrip supply?

|

In this context, RCC can be defined as follows:

"Given the uncertainty that our resources can supply hours according to the assumed project/non-project ratio, the fluctuations in non-project demand, and the overall deficit in project capacity, there is about 50% chance that we will be able to deliver the projects we are expected to deliver within the next 12 months."

Case study: Non-project work is probably taking far more time than you might like

CASE STUDY

Industry Government

Source Info-Tech Client

"When our customers get a budget for a project, it’s all in capital. It never occurs to them that IT has a limited number of hours. "

Challenge

- A small municipal government was servicing a wide geographic area for information technology and infrastructure services.

- There was no meaningful division of IT resources between support and project work.

- Previous IT leadership tried a commercial PPM tool and stopped paying maintenance fees for it because of lack of adoption.

- Projects were tracked inconsistently in multiple places.

Solution

- New project requests were approved with IT involvement.

- Project approvals were entirely associated with the capital budget required and resourcing was never considered to be a constraint.

- The broad assumption was that IT time was generally available for project work.

- In reality, the IT personnel had almost no time for project work.

Results

- The organization introduced Info-Tech’s Grow Your Own PPM Solution template with minor modifications.

- They established delivery dates for projects based on available time.

- Time was allocated for projects based on person, project, percentage of time, and month.

- They prioritized project allocations above reactive support work.

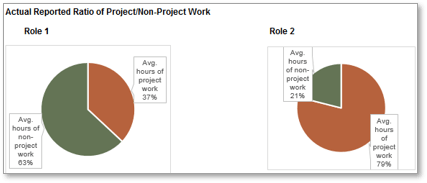

Validate your resourcing assumptions with your staff by surveying their use of time

Embrace the reality of imperfect IT labor efficiency to improve your understanding of resource time spend.

Use Info-Tech’s time-tracking survey to validate your resourcing assumptions and get additional information to improve your understanding of resource time spent: imperfect labor efficiency and continuous partial attention.

Causes of imperfect IT labor inefficiency

- Most IT tasks are unique to their respective projects and contexts. A component that took 30 minutes to install last year might take two hours to install this year due to system changes that occurred since then.

- Many IT tasks come up unexpectedly due to the need to maintain and support systems implemented on past projects. This work is unpredictable in terms of specifics (what will break where, when, or how).

- Task switching slows people down and consumes time.

- Problem solving and solution design often requires unstructured time to think more openly. Some of the most valuable solutions are conceived or discovered when people aren’t regimented and focused on getting things done.

Info-Tech Insight

Part of the old resource management mythology is the idea that a person can do (for example) eight different one-hour tasks in eight hours of continuous work. This idea has gone from harmlessly mistaken to grossly unrealistic.

Constant interruptions lead to continuous partial attention that threatens real productivity

There’s a difference between being busy and getting things done.

“Working” on multiple tasks at once can often feel extremely gratifying in the short term because it distracts people from thinking about work that isn’t being done.

The bottom line is that continuous partial attention impedes the progress of project work.

Research on continuous partial attention

- A study that analyzed interruptions and their effects on individuals in the workplace found that that “41% of the time an interrupted task was not resumed right away” (Mark, 2015).

- Research has also shown that it can take people an average of 23 minutes to return to a task after being interrupted (Schulte, 2015).

- Delays following interruptions are typically due to switching between multiple other activities before returning to the original task. In many cases, those tasks are much lower priorities – and in some cases not even work-related.

Info-Tech Insight

It may not be possible to minimize interruptions in the workplace, as many of these are considered to be urgent at the time. However, setting guidelines for how and when individuals can be interrupted may help to limit the amount of lost project time.

"Like so many things, in small doses, continuous partial attention can be a very functional behavior. However, in large doses, it contributes to a stressful lifestyle, to operating in crisis management mode, and to a compromised ability to reflect, to make decisions, and to think creatively."

– Linda Stone, Continuous Partial Attention

Define the goals and the scope of the time-tracking survey

1.2.5

30 minutes

Input

Completed Resource Management Supply-Demand Calculator

Output

Survey design for the time-tracking survey

Materials

N/A

Participants

- PMO Director

- Functional Managers

- Project Managers

Discuss the following with the activity participants:

- Define the scope of the survey

- Respondents: Comprehensive survey of individuals vs. a representative sample using roles.

- Granularity: decide how in-depth the questions will be and how often the survey will be delivered.

- Data Collection: what information do you want to collect?

- Proportion of project vs. non-project work.

- Time spent on administrative tasks.

- Prevalence and impact of distractions.

- Worker satisfaction.

- Determine the sample time period covered by the survey

- Info-Tech recommends 2-4 weeks. Less than 2 weeks might not be a representative sample, especially during vacation seasons.

- More than 4 weeks will impose unreasonable time and effort for diminishing returns; data quality will begin to deteriorate as participation declines.

- Determine the survey method

- Use your organization’s preferred survey distributor/online survey tool, or conduct one-on-one interviews to capture data.

1.2.5 continued - Refine the questionnaire to improve the relevance and quality of insights produced by the survey

Start with Info-Tech’s recommended weekly survey questions:

- Estimate your daily average for number of hours spent on:

- Total work

- Project work

- Non-project work

- How many times are you interrupted with “urgent” requests requiring immediate response in a given day?

- How many people or projects did you complete tasks for this week?

- Rate your overall satisfaction with work this week.

- Describe any special tasks, interruptions, or requests that took your time and attention away from project work this week.

Customize these questions to suit your needs.

Info-Tech Insight

Maximize the number of survey responses you get by limiting the number of questions you ask. Info-Tech finds that participation drops off rapidly after five questions.

1.2.5 continued - Communicate the survey goals and steps, and conduct

the survey

- Communicate the purpose and goals of the survey to maximize participation and satisfaction.

- Provide background for why the survey is taking place. Clarify that the intention is to improve working conditions and management capabilities, not to play “gotcha” or hold workers accountable.

- Provide a timeline so expectations are clear about when possible next steps will occur, such as

- Sharing and analyzing results

- Making decisions

- Taking action

- Reiterate what people are required or expected to do and how much effort is required. Provide reasonable and realistic estimates of how much time and effort people should spend on audit participation.

- Distribute the survey; collect and analyze the data.

Info-Tech Insight

Make sure that employees understand the purpose of the survey. It is important that they give honest responses that reflect the struggles they are encountering with balancing project and non-project work, not simply telling management what they want to hear.

Ensuring that employees know this survey is being used to help them, rather than scolding them for not completing work, will give you useful, insightful data on employee time.

Use Info-Tech’s Time-Tracking Survey Email Template for facilitating your communications.

Info-Tech Best Practice

Provide guidance to your resources with examples on how to differentiate project work vs. non-project work, administrative vs. keep-the-lights-on work, what counts as interruptions, etc.

Optimize your project portfolio to maintain continuous visibility into capacity

Now that you have a realistic picture of your realized project capacity and demand amounts, it’s time to use these values to tailor and optimize your resource management practices.

Based on desired outcomes for this phase, we have

- Determined the correct course of action to resolve your supply/demand imbalances.

- Assessed the overall project capacity of your portfolio.

- Cataloged sources of project and non-project demands.

- Performed a time audit to create an accurate and realistic picture of the time spent on different types of work.

In the next phase, we will:

- Wireframe a resource management process.

- Choose a resource management tool.

- Define data collection, analysis, and reporting steps within a sustainable resource management process.

Screenshots from tab 6 of the Time Audit Workbook.

Info-Tech Insight

The validity of traditional, rigorous resource planning has long been an illusion because the resource projections were typically not maintained. New realities such as faster project cycles, matrix organizations, and high-autonomy staff cultures have made the illusion impossible to maintain.

If you want additional support, have our analysts guide you through this phase as part of an Info-Tech workshop

Book a workshop with our Info-Tech analysts:

- To accelerate this project, engage your IT team in an Info-Tech workshop with an Info-Tech analyst team.

- Info-Tech analysts will join you and your team onsite at your location or welcome you to Info-Tech’s historic Toronto office to participate in an innovative onsite workshop.

- Contact your account manager (www.infotech.com/account), or email Workshops@InfoTech.com for more information.

The following are sample activities that will be conducted by Info-Tech analysts with your team:

1.1.2 Assess the current distribution of accountability for resource management practice

Discuss who is currently accountable for various facets of resource management, and whether they have the right authority and ability to deliver on that accountability.

1.2.1 Create realistic estimates of supply and demand using Info-Tech’s Supply-Demand Calculator

Derive actionable, quantitative insight into the resourcing challenges facing the organization by using Info-Tech’s methodology that prioritizes completeness over precision.

Phase 2

Design a Realistic Resource Management Process

Phase 2 Outline

Call 1-888-670-8889 or email GuidedImplementations@InfoTech.com for more information.

Complete these steps on your own, or call us to complete a guided implementation. A guided implementation is a series of 2-3 advisory calls that help you execute each phase of a project. They are included in most advisory memberships.

Guided Implementation 2: Draft a Resource Management Process

Proposed Time to Completion (in weeks): 3-6 weeks

Step 2.1: Determine the dimensions of resource management

Start with an analyst kick-off call:

- Introduce the seven dimensions of resource management

- Trade-off between granularity and utility of data

Then complete these activities…

- Decide on the seven dimensions

- Examine the strategy’s cost-of-use

With these tools & templates:

Resource Management Playbook

Step 2.2: Support your process with a resource management tool

Discuss with the analyst:

- Inventory of available PPM tools

- Overview of Portfolio Manager Lite 2017

Then complete these activities…

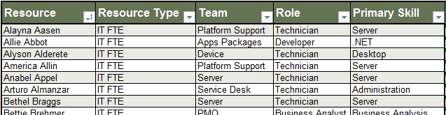

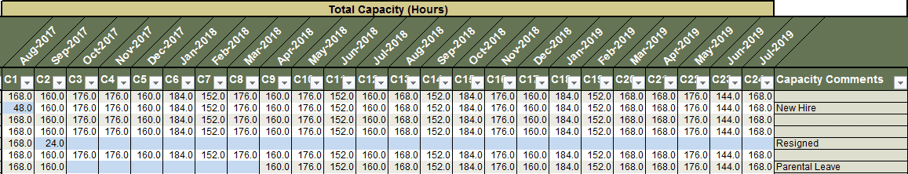

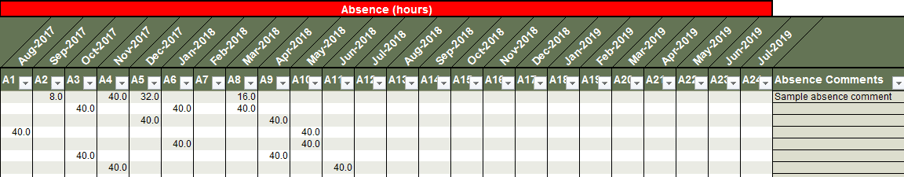

- Populate the tool with data

- Explore portfolio data with the workbook’s output tabs

With these tools & templates:

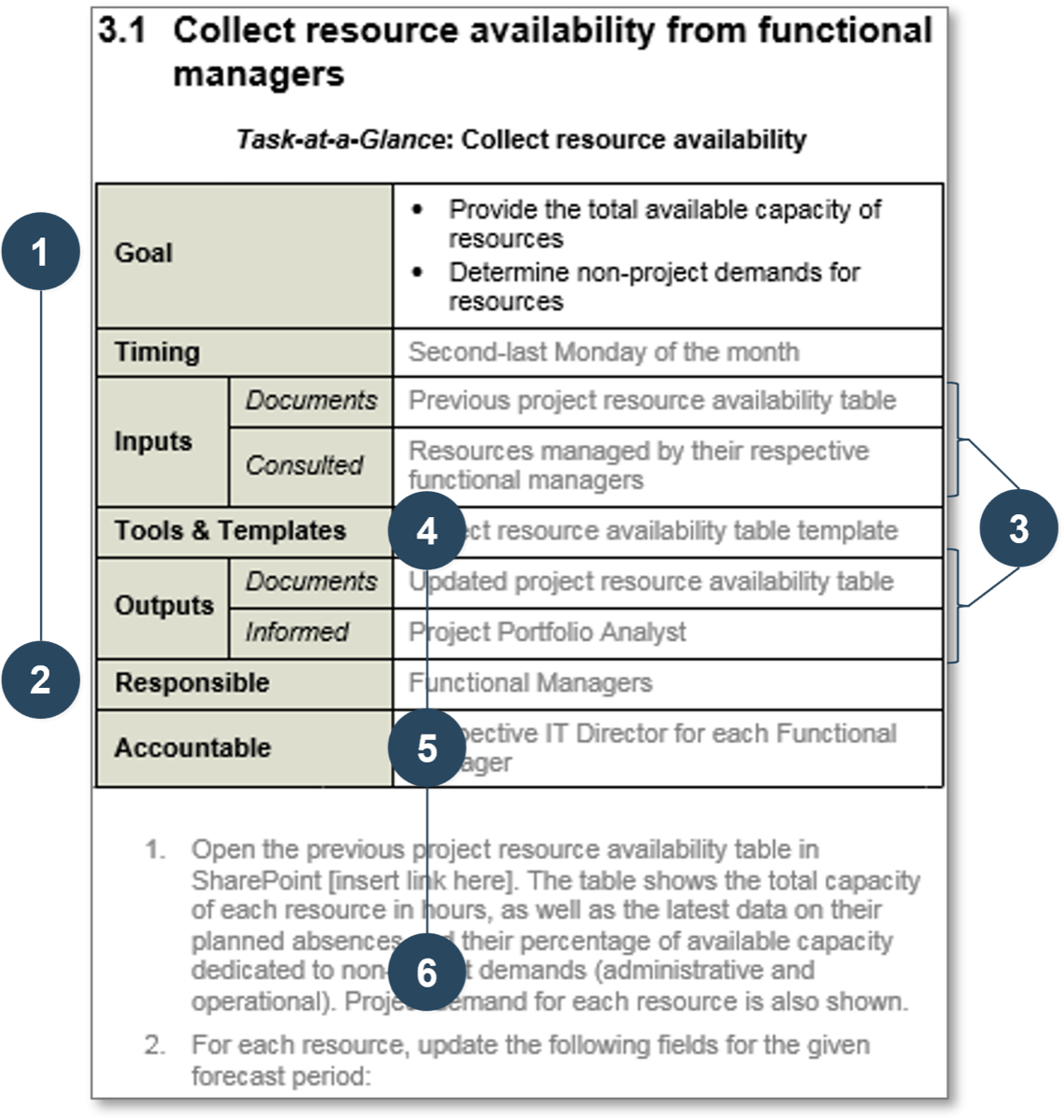

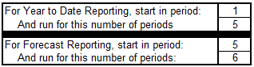

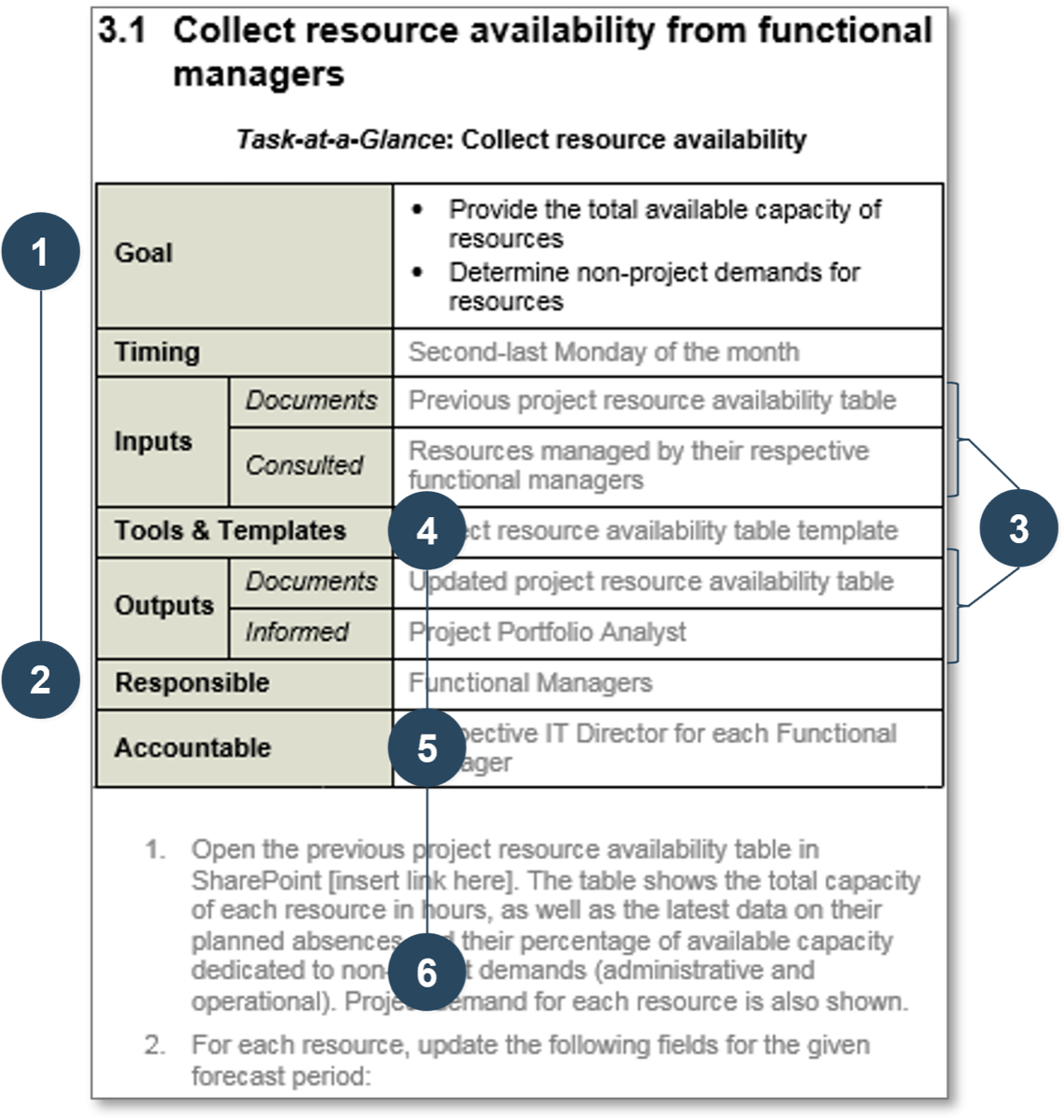

- Portfolio Manager Lite