Your Company is an Economy: Why This is Your Secret Weapon for Resilience

IT specialists often instinctively focus on technical issues, such as server failures or network problems, because they are trained to address the broken parts. However, it's important to consider the context in which these occur. But what if the real problem isn't just the part but the entire system it operates in?

I want you to take a step back and to stop thinking about your company as a collection of departments and IT systems. Start seeing it for what it truly is: a complex, living, breathing economic system. This isn't some academic analogy. It’s a powerful model that will change how you approach resilience.

An economic system involves production, resource allocation, and distribution of goods and services, which parallels how a company operates internally. It includes the combination of various departments, the people doing things, the business units, and even the decision-making steps that make up the economic structure of your company. Once you see this, you can never unsee it.

What is an economic system?

Let’s quickly demystify this. Forget textbooks and complex theories for a moment. Think about a national economy. It does three basic things:

-

Production: It makes things. Factories build cars, farms grow food, and programmers write software. This is the creation of value.

-

Resource Allocation: This process decides who gets what to make those things. Who gets the steel for the cars? The land for the farms? The funding for the software developers? These are all decisions about how to use scarce resources.

-

Distribution: This process gets the finished products to the people who need them. Cars go to importers, then dealerships then the customers, food goes to grocery stores, and software gets deployed to servers and then used by clients (in the general sense).

That's it. Production, allocation, distribution. Every economy, from a simple bartering tribe to the global financial market, operates on these principles. And so does your company.

So, how is your company an economy?

Your company doesn't just “do work.” It produces, allocates, and distributes services in its own internal market (and eventually sells outside, otherwise… trouble).

The production is everywhere. The human resources department produces a “payroll service.” The sales department produces “revenue contracts.” And the IT department? It produces a vast array of services: “compute cycles,” “data storage,” “network connectivity,” and “application uptime.” These are the goods and services that every other part of the company consumes to do their jobs.

Resource allocation is the lifeblood of your corporate economy. It's the annual budgeting process, the project prioritization meetings, and the daily decisions managers make about where to assign their people. In IT, you are equally part of the allocation process. Most people get to decide at least what they will give priority to that day. Perhaps via the daily scrum or stand-up meetings. Perhaps during the review process. As a manager, when you approve a request for a new high-powered virtual machine for one team, you are making an economic choice. You are allocating a scarce resource that another team can no longer use. As a developer, when you decide that task X is now a higher priority than task Y, you make an economic decision to allocate yourself to task X. It's important to understand that there is an opportunity cost to every decision, whether you label it that way or not.

And distribution? That's how these services get to their “consumers.” It’s the internal platforms, the APIs that connect applications, the service desk that fulfills requests, the operations teams that update data via forms into databases, and even the reporting dashboards that deliver information. These are the supply chains and logistics networks of your company’s economy. The consumers are your clients, of course, but also every department that uses a service provided by another department.

The IT department plays a central role in the company's economy, akin to a central bank and infrastructure provider, by managing essential digital resources like compute, storage, and bandwidth. You control its supply and, through your decisions, influence its value. You also build and maintain the “roads” and “power grid”—the networks and platforms—that the entire corporate economy depends on to function.

Why This Perspective Is Important for Resilience

This is where I feel it gets fascinating. When you start seeing your company as an economic system, your understanding of resilience deepens dramatically. You move beyond simply fixing broken things and start thinking about stabilizing a complex, interconnected market.

It helps you understand true systemic risk.

When a core database goes down, an engineer sees a technical failure. An economist sees a supply chain collapse. That database isn't just a box with blinking lights; it's a critical supplier of a raw material, namely data. Every single business process, application, and team that creates, updates or consumes that data is now starved of a resource they need to produce their own services. The failure cascades not just through technical dependencies but through economic dependencies. Seeing it this way forces you to ask better questions: Who are the biggest “consumers” of this data supplier? What is the total economic impact of this outage, not just the technical impact? This changes the incident's priority and your response strategy.

You move beyond simple redundancy.

The traditional engineering approach to resilience is redundancy. If one server is important, have two. This is like a town having two power plants. It's a good start, but it's not true economic resilience. An economist would ask different questions. Can we diversify our suppliers? Can we re-route via another path? If our primary database provider fails, can we switch to a secondary one, even if it's slower or pricier for a short time? This is the principle of substitution. Can a business process continue to function in a degraded mode, producing a lower-quality “good” for a while instead of stopping completely? This is about economic adaptability, not just technical duplication.

You could take this even further and move into the realm of business continuity. Can your process work when your primary resource (the database) is not available? How would you redesign your process to work with an alternative solution? This thinking is at the heart of modern operational resilience regulations worldwide. Authorities are no longer just asking if your backups work; they're asking if your firm can fulfill its economic function in the face of severe adversity. They demand a clear grasp of your entire supply chain and a testable exit plan for critical suppliers, including cloud providers.

You see that this goes way beyond a failing-part view. It goes to the heart of the economic function of your company.

Incident response becomes economic intervention.

During a major incident, the incident commander is now no longer just a technical coordinator. You are the head of the “central bank” during a "market crash". Your job is to prevent a localized failure from causing a full-blown corporate recession. Think about your actions:

-

You allocate scarce capital (your top engineers' time) to the most critical problem. The economic cost is the non-delivery of any other product by those people.

-

You implement fiscal policy by prioritizing certain fixes over others to stimulate the quickest “economic” recovery.

-

You manage market confidence through clear, calm, and regular communication to stakeholders, preventing panic from spreading.

Each decision is an economic intervention designed to restore stability to the system. (If that is not the job description of a central banker, then I eat my hat.)

Side Note: I often see teams who are obsessed with their own service's uptime, their own local metrics. They proudly report “five nines” of availability, but they do not report on how their service is actually consumed or how critical it is to the company's overall economic output. They've optimized their own factory but don't disclose their output's need level to the company or that their occasional one-hour outage brings the entire company's main assembly line to a halt. Resilience is not about local optimization; it is about the stability of the entire economic system. A dashboard that lists teams in order of availability or whatever other metric is fine, but these numbers must be mapped against their economic relevance. Without the economic relevance weighting, you may be misallocating resources in areas that are not critical or sufficiently important.

How to Start Thinking Like an Economist in Your Resilience Practice

This isn't just a theoretical exercise. You can apply this model today to make your organization stronger and yourself more effective to any employer or client.

First, map your economic flows. Go beyond standard architecture diagrams. Create maps that show how value and services are produced, distributed, and consumed across departments. Identify your most important “supply chains.” Ask business units what IT services are essential for their “production lines” and what the financial impact is when those services are unavailable. This gives you a heat map of economic risk.

Second, identify your single points of economic failure. In every economy, there are institutions that are “too big to fail.” What are yours? Is it a single authentication service? A legacy mainframe? A specific team of two people who know how a critical system works? These are the areas where a failure will cause a systemic crisis. They require more than just technical redundancy; they need deep, thoughtful resilience planning, including succession plans for people and substitution options for technology.

Finally, reframe your post-incident reviews. Stop just asking, “What broke and why?” Start asking, “Which economic activity was disrupted?” and “How did the disruption flow through the system?” This shifts the conversation from blaming a component or a team to understanding systemic weaknesses in your company's economy. The goal is not to find a guilty party but to identify where your internal market is fragile and how you can strengthen it with better “monetary policy” (resource allocation) or “infrastructure” (more robust platforms).

The vicious cycle of a failing economy

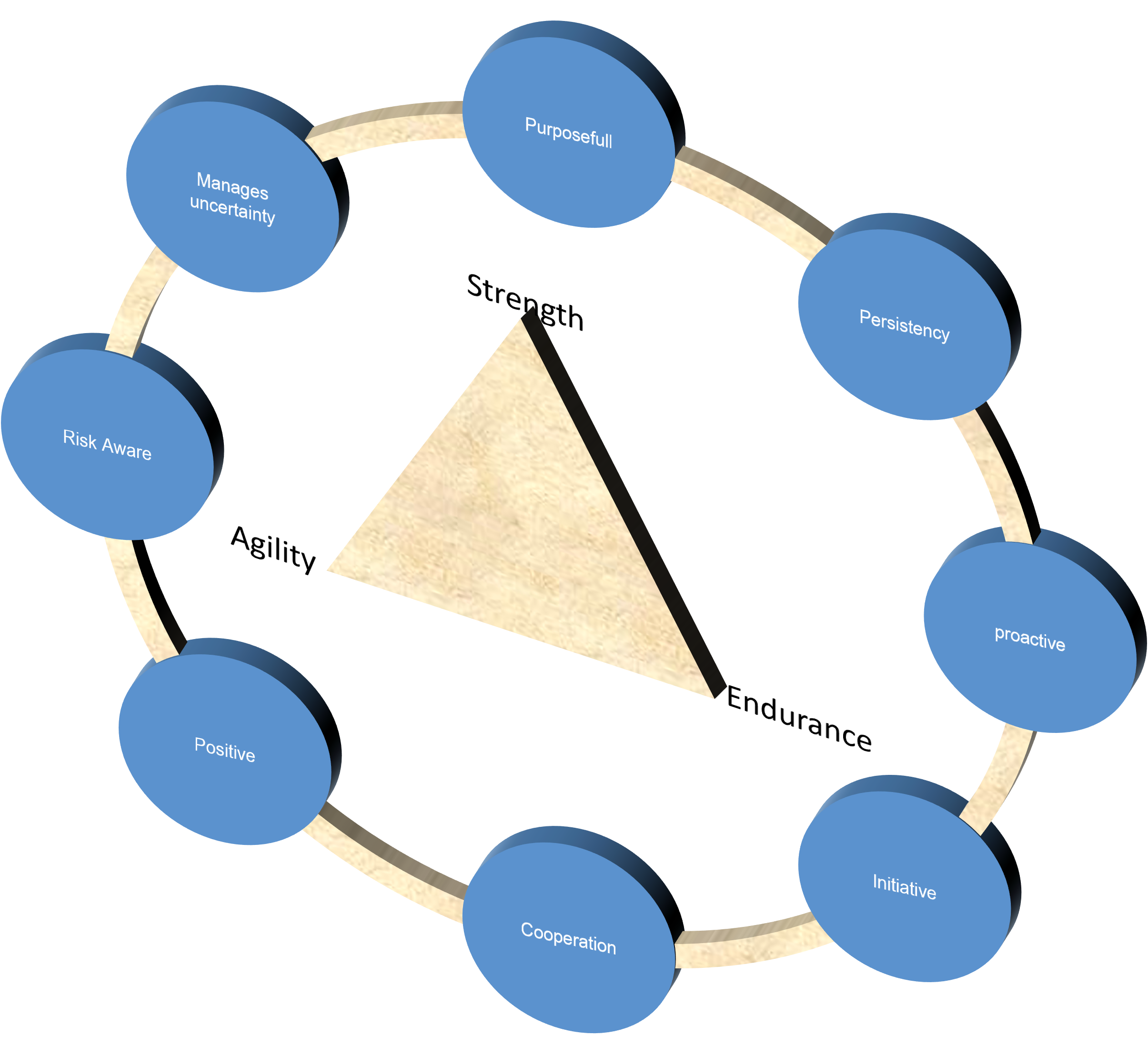

In another article, I mentioned that resilience is a mindset.

So what happens when this economic system becomes unstable?

These issues are typically considered failures and they manifest as irritations, perceived slowness and bugs, all the way to (regular) failures of a process or whole system.

If this broken economic system is allowed to remain unstable, people will adopt negative behaviors.

When “the government” (IT) fails to deliver, business teams take matters into their hands and start shadow IT. They may even purchase their own subscriptions.

In a stable economy, participants trust that resources will be available when needed, but in a broken system, that trust is gone and leads to the hoarding of assets. This may be visible in the requested need for time or even budget allocation. And that leads into protectionism where teams build walls around their data and systems.

When failures are common, the focus shifts from resolving the systemic problems to assigning blame for the specific symptom. This is akin to the breakdown of trade relations. The applications team blames the infrastructure team for slow servers. The infrastructure team blames the network team for latency. The network team blames the applications team for inefficient code. And around we go.

Taking it just that little step further: If people live in a failing state long enough, they lose hope. This is learned helplessness. Your most valuable “citizens”—your engineers and business users—become disengaged. They stop reporting bugs because they assume they will never be fixed. They stop suggesting process improvements because they believe their voice doesn't matter.

And lastly: In a functional system, there are clear processes for requesting services. In your broken economy, these official channels are considered worthless. The only way to get anything done is to generate a crisis. Escalation becomes the primary currency. People learn to bypass the ticketing system and send direct messages to senior leaders because they perceive that's the only way to get a response.

How to Break the Cycle: Start Small

To break this cycle, you need to start small and use mechanisms that turn the negative effects of problems into positive effects, like seeing opportunities.

- Opportunities to correct irritations

- Opportunities to enhance processes

- Opportunities to perhaps redesign a service

Proposing a grand vision will get you polite nods and zero action. I recommend you pick one irritation and fix it. Repeat multiple times until staff starts to perceive a change. Don't try to move the mountain. Remove the first obstacle and make your way up from there. This can be solving an issue, reducing an uncertainty, or actually spotting a way forward.

It will go easier as you continue this. Accept that on day one, your credibility is zero. It doesn’t matter whether you're a new manager or a seasoned expert. Trust is earned on the factory floor. Fix one small, nagging irritation for one person. Then another. This is how you build the political and social capital needed to tackle the mountain. It takes time.

But what will happen next is crucial. There will be a reduction of the negative behaviors. And when you work it efficiently with enough time, you will eliminate those behaviors. And yes, there will be many ifs and buts, and each of the broken elements of a larger chain may require their own solutions. But it is this act of seeing the bigger picture through the constituent parts that will allow you to assign priorities and move closer to the solution in a structural way.

Seeing step by step results feeds positivism and higher stability. Which in turn again feeds more positivism.

When you view your company through the lens of an economic system, it elevates the practice of resilience from a purely technical discipline to a value function. It gives you a language to communicate impact and risk to leadership in terms they understand: production, supply, and cost.

It forces you to see the interconnectedness of everything you do and to appreciate that the failure of a single, seemingly minor component can have large, cascading effects across the entire organization. By thinking like an economist, you stop being just a firefighter, putting out isolated blazes. You become the architect of a more stable, more robust, and ultimately more resilient economy.

You become the architect of a more stable, more robust, and ultimately more resilient economy. Now, go manage it.

Request a Strategic Command Briefing

This intake requires the input of a management body member or CxO. Please provide the institutional context required to initiate a resilience diagnostic and determine architectural alignment.

This site and all contents is © 2026 Tymans Group BV